The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

The monkey selfie is back!

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) is continuing to press its case, now on appeal in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, that the macaque monkey named Naruto snapped the famous "monkey selfie" - an iconic image for our times if ever there were one - and should be considered the "author" of the work within the meaning of U.S. copyright law.

It is impossible to talk about the case without making it sound ridiculous; indeed, it is ridiculous, as in "an exceptionally easy target for ridicule." But as America's only (I think) primatologist-turned-copyright-law-professor, I find it impossible for me not to talk about it. And as I've said before [see "I'd be smiling, too, if I owned the copyright to this photograph"], PETA's claim that the monkey owns the copyright to the photo touches on some pretty intriguing copyright issues that, in an age of robots and machine creation*, are likely to have some wider significance down the road.

[UPDATE 9-2-2016: Funnily enough, this just crossed my desk: IBM's Watson has apparently helped create a trailer for the film "Morgan," in advance of its forthcoming release. Does it own copyright in that? Does IBM? or Naruto, perhaps?]

Not that I think that PETA's claim will succeed. There are many reasons that copyright law does not and should not deem Naruto to be an "author," ranging from the purely practical (e.g., How do we know the monkey's name is "Naruto," and that he was the one that snapped the photo? What if no human had been there to see him do so - is there still a copyright, and does he own it? Insofar as copyright in a work endures for the life of the author plus 70 years, who's keeping track of this wild macaque's lifespan, and how will we know when it's over?) to the more abstract: Copyright's fundamental rationale is that bestowing protection on works is a means of providing "authors" with an incentive that they otherwise would not have to create those works in the first place; non-humans (and machines, for that matter) can't be "authors" because they won't be and can't be incentivized by the existence of copyright protection for their works.

But continuing in the "it's worth taking seriously" vein, I read an amicus brief submitted in support of PETA's position by an anthropology professor and primatologist at Notre Dame, Agustín Fuentes. Prof. Fuentes's brief argues that the scientific data "conclusively demonstrates that primates have complex social cognition, and are able to manipulate objects to obtain desired effects," that "the series of behaviors that resulted in the manipulation of the camera, and subsequent image creation, by Naruto are well within the range of normative manipulation abilities expressed by multiple primate species," and that these behaviors "should be seen as intentional and original acts that led to the creation of an image."

But Fuentes's brief, inadvertently, illustrates all too clearly why the monkey can't be the "author" of the photograph. Naruto, he writes,

… like other macaques, had likely made the connection between manipulation of the camera as an item and the sound of the shutter and the changing image in the lens as the shutter clicked. This may have been interesting for Naruto as he was noted as performing this behavior many times. It is likely that he had seen the human manipulation of the camera and heard the sounds it made and, as is common for macaques, became curious to investigate it on his own…. Naruto's behavior in creating the photographs in dispute is consistent with a macaque's interest in and capacity for sophisticated object manipulation. Naruto certainly understood that he was intentionally engaged in actions with an object that was stimulating. He could recognize the association between his actions and the shutter movement and sound. These photographs are not the result of an accident; they result from specific and intentional manipulation of the camera by Naruto.

I buy all that; the monkey (if indeed it was Naruto) performed an intentional manipulation of the camera to achieve a desired result. But that's not enough to claim "authorship" of the resulting work.

As Fuentes himself acknowledges, "this in no way assumes Naruto had any cognizance of the concept of a photograph but rather that the actions and noises made by the camera were enticing and that through explorative manipulation Naruto was able to cause the camera to make such sounds/actions."

But that's the rub. Pressing a button because it makes a nice funny sound isn't "authorship" of the resulting photograph (whether it's done by a monkey or my 10-month-old granddaughter, who really loves pressing buttons to make funny sounds), because authorship requires the awareness that a "work" is, in fact, being created.

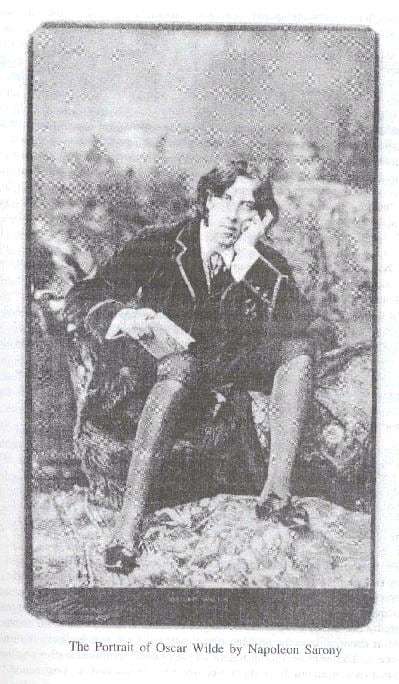

Justice Samuel Miller made this point many years ago, in his opinion for the Supreme Court in one of my favorite copyright cases of all time, Burrow-Giles Lithographic v. Sarony., 111 US 54 (1884). Sarony, a well-known photographer, had snapped, and claimed copyright in, the portrait of Oscar Wilde shown above.

[One of the most popular photographs in history, incidentally - even by 1884, it had sold 85,000 copies, and it is still on sale, amazingly enough, in the museum store at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York - last visited August 23, 2016].

The defendant argued that there was no copyright in the photo because it was "the mere mechanical reproduction of the physical features or outlines of some object animate or inanimate, and involves no originality of thought or any novelty in the intellectual operation connected with its visible reproduction in shape of a picture." The court disagreed; that "may be true in regard to the ordinary production of a photograph," but not for this photo:

The third finding of facts says, in regard to the photograph in question, that it is a 'useful, new, harmonious, characteristic, and graceful picture, and that plaintiff made the same . . . entirely from his own original mental conception, to which he gave visible form by posing the said Oscar Wilde in front of the camera, selecting and arranging the costume, draperies, and other various accessories in said photograph, arranging the subject so as to present graceful outlines, arranging and disposing the light and shade, suggesting and evoking the desired expression, and from such disposition, arrangement, or representation, made entirely by plaintiff, he produced the picture in suit."

These findings, we think, show this photograph to be an original work of art, the product of plaintiff's intellectual invention, of which plaintiff is the author.

That's the funny thing about copyright. It protects "original mental conceptions," to which the author gives "visible form." Sarony conceived of a picture - a "work of authorship" - and then he went out and did what needed to be done, including the pressing of buttons, to give that work a "visible form."

Naruto, clever monkey that he may be, didn't (as far as we know) do that. He didn't understand that he's creating a photograph, and without that, I don't think he can claim copyright in it (even if he could talk).

Show Comments (0)