The Truth About the Biggest U.S. Sex Trafficking Story of the Year

- Part 1: 'This Is What Human Trafficking Looks Like'

- Part 2: How Washington Police Turned Talking About Prostitution into a Felony Offense

- Part 3: From 'Prostituted Woman' to Human Trafficker

- Coda: A Lifetime of Stigma

PART ONE: 'This Is What Human Trafficking Looks Like'

With the death of his mother last summer, Sigurds Zitars, a retired accountant, was the only family member left in University Place, Washington. Since 2006 "Sig" had been the clan's caregiver, after his mother developed dementia and his father and sister both took ill. In January, Zitars was fixing up the family home for sale when police broke down its door, arresting the 62-year-old at gunpoint. According to the state, Zitars was one of at least a dozen bad guys associated with an elite league of sexual predators and a multi-state sex-trafficking ring.

News of the bust played perfectly into the growing narrative from both activists and officials that sex trafficking—the use of force, fraud, or coercion to trap people in prostitution—is rampant in America, a pernicious form of what Barack Obama described in 2012 as "modern slavery." According to political lore, both girls-next-door and women smuggled across U.S. borders are at risk, their exploitation aided by online tools and the indifference of lusty patrons.

On January 7, Washington officials unveiled a perfect storm of such horrors: Women lured from South Korea under false pretenses and "held against their will" at local brothels. A website where deviant men promoted and reviewed these enslaved women. "Because they had money," said King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg at a televised press conference, these men "gained access to sexually abuse these vulnerable young women, then put their energies toward a campaign to encourage many more men to do the same."

"The systematic importation of vulnerable young women for sexual abuse, exploitation, and criminal profiteering has been going on for years and it came to a stop this week," Satterberg added. "This is what human trafficking looks like."

But as more information about the case has become available, Satterberg's narrative starts to break down. The reality—as evidenced by police reports, court documents, online records, and statements from those involved—is far less lurid and depraved. Instead of a story of stark abuse and exploitation, it's a story of immigration, economics, the pull of companionship and connection, the structures and dynamism that drive black markets, and a criminal-justice system all too eager to declare women victims of the choices they make.

The story is presented here in three parts. The first offers a glimpse at how this sexual economy actually operated, the motivations of its main actors, and how police came to "infiltrate" the scene. Part two explores how the government's war on prostitution—rebranded as a war on sex trafficking—brands innocent men as sexual predators and sets dangerous new standards of disrespect for free speech and free association rights. And part three looks at how policies designed to get tough on pimps and traffickers wind up threatening the very women they're supposed to save.

'Shipped From City to City'

The first wave of arrests came just after New Year's. On January 6, working with the FBI and the Bellevue Police Department (BPD), officers from the King County Sheriff's Office (KCSO) raided 12 upscale apartments in Bellevue, a large and affluent suburb of Seattle that's become a hub of tech industry. At a press conference the next day, they announced that 12 female victims from South Korea had been rescued, 12 "brothels" closed, and a major human-trafficking ring shut down.

The team also seized three websites: The Review Board (TRB), a web forum where Seattle sex workers and clients communicated; KGirlsDelights.com, a directory of Korean sex-workers and escort-agencies in America; and TheLoeg.com, a private site for local prostitution story-swapping. TRB was run by "Tahoe Ted"—otherwise known as Sigurds Zitars—arrested the day prior along with nine suspected members of the LOEG (or "League," as police spelled it).

Prosecutor Dan Satterberg described the situation as one of extreme coercion and criminality, calling the 12 Asian women recovered in the operation "true victims of human trafficking."

News of the bust soon spread in sensational newscasts and lurid headlines. The U.K.'s Daily Mail summed the story up like this: "Police smash prostitution ring and rescue 12 South Korean women forced into $300-an-hour prostitution by ex marijuana grower who pimped them out across the U.S."

A Bellevue paper claimed the Korean women were "required to work off their family's debts through sexual service." The Seattle Times reported that police had thwarted "a widespread prostitution ring run by a group of men known as 'The League.'" Local news network KIRO 7 named photographer Michael Durnal and ex-marijuana entrepreneur Donald Mueller as the ringleaders, men who "sold women all over" America.

It was shocking, scandalous, horrifying. Yet almost none of it is true.

While most publications were careful to pepper "police said" into articles, their headlines and language precluded any sense of impartiality. "12 women forced into prostitution freed near Seattle," trumpeted The Oregonian, over an Associated Press article. That article, syndicated widely, said Korean women were "shipped from city to city about every month and typically not allowed to leave their apartments except to go to the airport." The New York Times reported that the women were being "brought to America and forced into prostitution to pay debts" by a "major human trafficking ring." Reuters reported that victims were "forced to work as much as 14 hours per day."

Police, meanwhile, continued to expand the reach of the case. In early May, five months after the first arrests, six more men were added to the complaint against alleged League members. These new defendants included archetypes of the Seattle-Bellevue tech class, including an executive at Microsoft, an engineer for Boeing, and a director of software development for Amazon. Local media reported that these men were part of a "large-scale sex trafficking operation" and offered headlines such as "Microsoft and Amazon Execs Busted for Promoting Sex Slavery."

It was shocking, scandalous, horrifying. Yet almost none of it is true—and the little that is technically true is so lacking in context that it's utterly misleading.

Almost everything that follows was known by detectives prior to their January raids and press conference, because it comes directly from court documents that they filed to establish probable cause for each defendant's arrest. However, the picture that emerges from these documents bears little resemblance to the dramatic and dystopian tale that police publicly spun.

Distorted Details

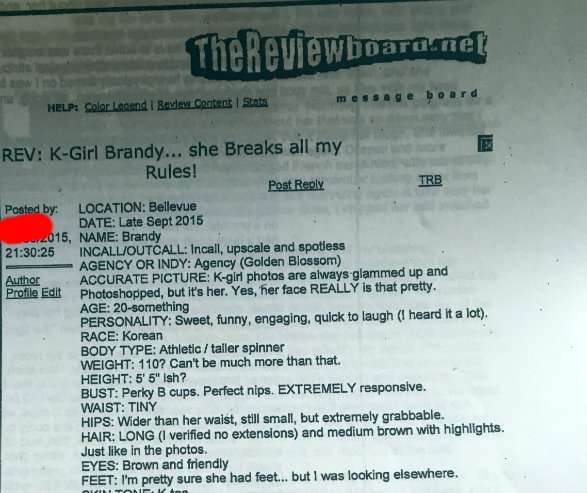

Begin with police's claim that The Review Board was a "sex trafficking website" where "prostituted women" were advertised and reviewed. This implies the women promoted on TRB had no control over their ads appearing there, did not want clients to review them, and generally did not want to be engaged in commercial sex. On the contrary, the core of TRB's business model consisted of escorts posting advertisements for themselves. Countless Seattle-area sex workers who have advertised on the site have attested to this. As one, "Veronica," told the women's site Broadly, TRB "was really a wonderful thing that kept everyone safe. Girls would be in touch with each other. A lot of people used it as a reference system—have you seen this person and are they safe?—for both sex workers and clients."

That TRB worked as an advertising and review system designed to benefit both sex workers and their clients is not something detectives could have merely misunderstood. King County Detective Luke Hillman had been posting undercover on TRB for years—interacting with many defendants in this case—before any arrests were made. And not only were many of the women who advertised on TRB openly listed as "independent," police have in their possession hundreds of emails that show the women actively managing their businesses.

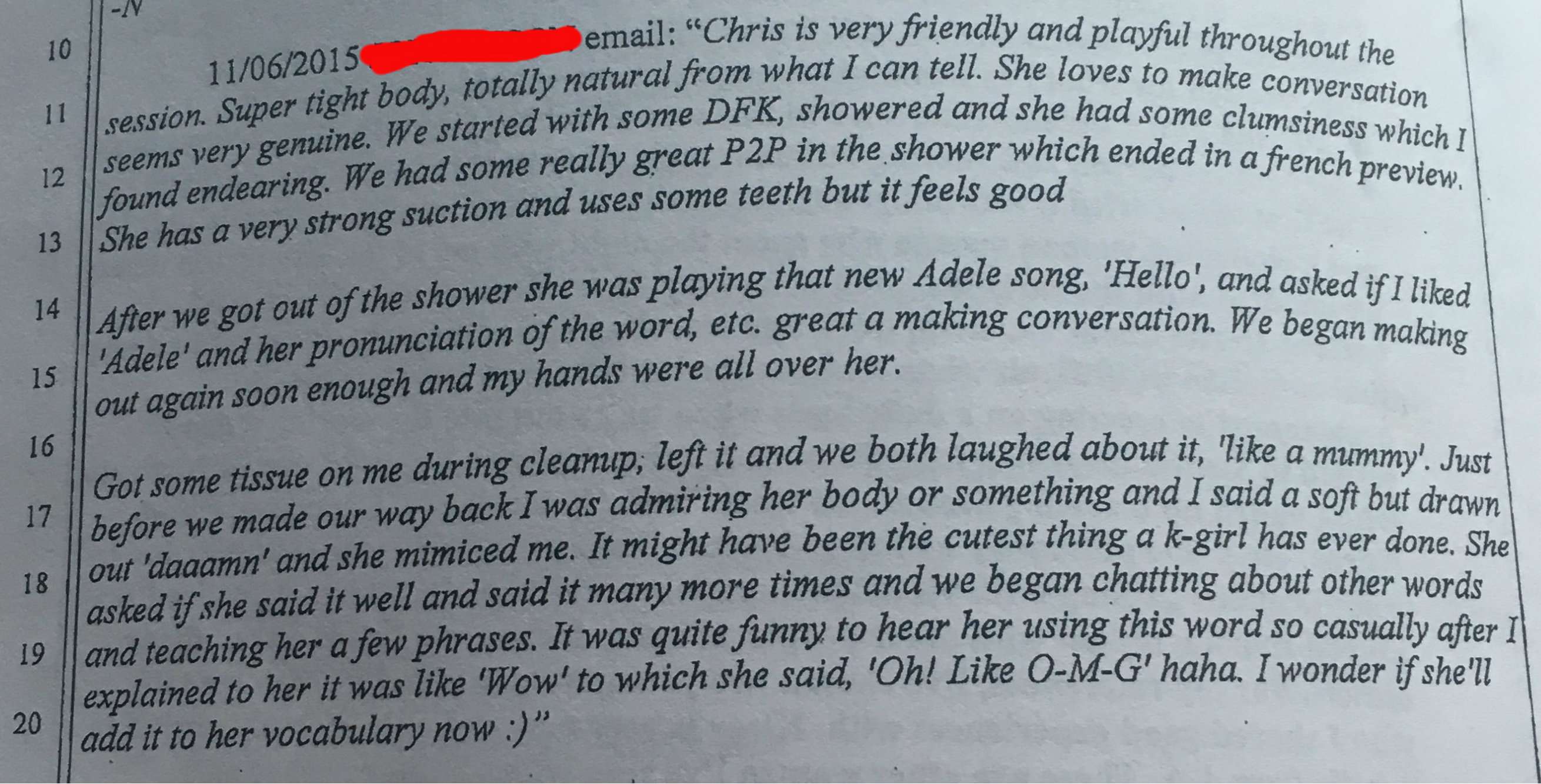

For instance, the Certificate for Determination of Probable Cause against Phillip Dehennis, who was charged with "promoting prostitution"—more on that particular charge later—highlighted a string of emails between him and sex worker "Sabreena." According to Bellevue Detective Tor Kraft, Dehennis and Sabreena "agree on a 90 minute session with her to which she would throw in a neck trim (actual hair cut) at 'No charge.'" After they meet, Dehennis emails Sabreena to ask explicitly, "Would you like me to put a review on TRB?" She says yes. When Dehennis completes the review, he emails her again and asks her to check it for accuracy, to which Sabreena replies "thank you so much for the review!" Dehennis was helping Sabreena market herself.

So what about the two men, Durnal and Mueller, whom KIRO 7 called sex-trafficking ringleaders who "sold women all over the country?" Nowhere in official court documents do police allege this; at most, Mueller and Durnal are accused of exploiting Korean sex workers—a.k.a. "K-Girls"—within the Seattle area.

But even the case for that is flimsy. Despite initially labeling both men "human traffickers," police present no substantial evidence in charging documents that local K-Girls were captive or unwilling. By all accounts, these women flew to Seattle voluntarily and without chaperones, usually from other U.S. cities, in order to work temporarily at one of the area's booming Korean-escort agencies. The K-Girls were, in essence, independent contractors.

"It is reasonable for women to choose sex work in the US instead of sex work in Korea," wrote Seattle resident Christina Slater, who describes herself as an "erotic service provider," in an April blog post about the Review Board bust. "I know that if those were my options…and if I spoke little to no English I would need assistance in finding a work place, scheduling clients, etc."

This is the main criminal activity alleged of Mueller and Durnal: providing K-girls with live-work space, posting online ads for them, and screening and booking their clients. Mueller called his enterprise "Asian Haven," while Durnal ran "K-Dynasty." Both operated out of rentals in high-end apartment complexes in downtown Bellevue. The men paid the rent and utilities on these spaces and stocked them with furniture and supplies, such as mouthwash and condoms, but did not live there. Visiting K-girls each got their own bedroom and private bathroom. In exchange for the room, advertising, and administrative work, Mueller or Durnal received $100 for each $300-an-hour "date" a woman completed.

Doesn't that make Mueller and Durnal "pimps"? Yes, in the sense that the definition of a pimp is anyone who helps manage business for a sex worker or makes money off of prostitution.

But Mueller and Durnal don't conform to pimp stereotypes. The men—both prolific sex buyers themselves—weren't violent or abusive. They didn't have sex with the women they booked, provide them with drugs, try to keep them dependent, or try to keep them from leaving (in fact, their business model depended on women coming and going relatively quickly). They provided a service and took a fee, leaving the K-Girls with whom they worked with a personal profit of hundreds of dollars per day.

Of course, being paid doesn't, on its own, preclude being exploited. What about the claims that the K-Girls were forced to work 12 to 14 hours daily?

The only evidence in police documents to support these statements is TRB advertisements that list escorts' appointment availability. Some ads did indeed indicate availability windows stretching 10 to 12 hours. But being available during those hours doesn't mean the women were actually working for all or even most of them. Mueller allegedly told police that his escorts saw an average of five clients per day, with a typical session lasting one hour.

It's similarly unclear on what basis police allege that K-Girls were trapped in the area or in their apartments. Probable cause documents for Mueller and Durnal offer nothing to support this accusation. A case summary for Mueller states that "Donald's sex workers typically travel via airplane to work at his brothels. His sex employees pay their own travel expense to get to Seattle. [They] fly in from different cities such as New York, Boston, or L.A." The summary also details an email between Mueller and a woman named "Ann" who claims to live out of the country.

Within the plans, the pair discuss how to get Ann to the U.S. legally so they [can] go into business together. Ann mentions that she will pay Donald to "Make appointments with customers.' Donald agrees to do some background work into the process and … explains that he will contact an immigration attorney he knows to assist.

Statements made by League members in their private communications also fail to create an impression that these women were hapless prisoners. For instance, after a session with K-Girl "Mari," one member reports that "she told me she's a total gym rat, spending about two hours a day in the gym." After another session, he reports that Mari "shared some videos of her doing weights in the gym. This girl can lift some weights!"

Even if Mari was making use of the building's rooftop gym, such activities suggest that, at the very least, she wasn't captive and could have reached out for help in some way had she wanted to. This interpretation is further supported by the fact that these women had internet-enabled phones, which they were able to use freely.

"Migrant sex workers, especially Asian migrant workers, are often inaccurately labeled as trafficking victims."

"They talked about going shopping, their favorite restaurants," one former client, who asked to remain anonymous, told me. "Their English was fine." Many came over on student visas, with the goal of making cash quickly in the sex trade before heading back to Korea, he said. One K-Girl who always took great pride in her nails told him she was saving up to open a nail salon and body-waxing spa back home.

"Migrant sex workers, especially Asian migrant workers, are often inaccurately labeled as trafficking victims," Savannah Sly, board president for the Sex Workers Outreach Project (SWOP), cautioned in a statement at the time of the bust. "Just because a women came to the U.S. and works as an escort does not mean she did so involuntarily."

There's little in police charging documents to suggest Seattle K-Girls were powerless over how long they stayed in the area. Yes, they frequently told customers they weren't sure how long they would stick around. But although this could be a sign someone is pulling the strings elsewhere, it could just as easily mean that they don't think it's the client's business, that it depends on how long the agency will let them, or—the reason they're most often reported to give—that it depends how business goes.

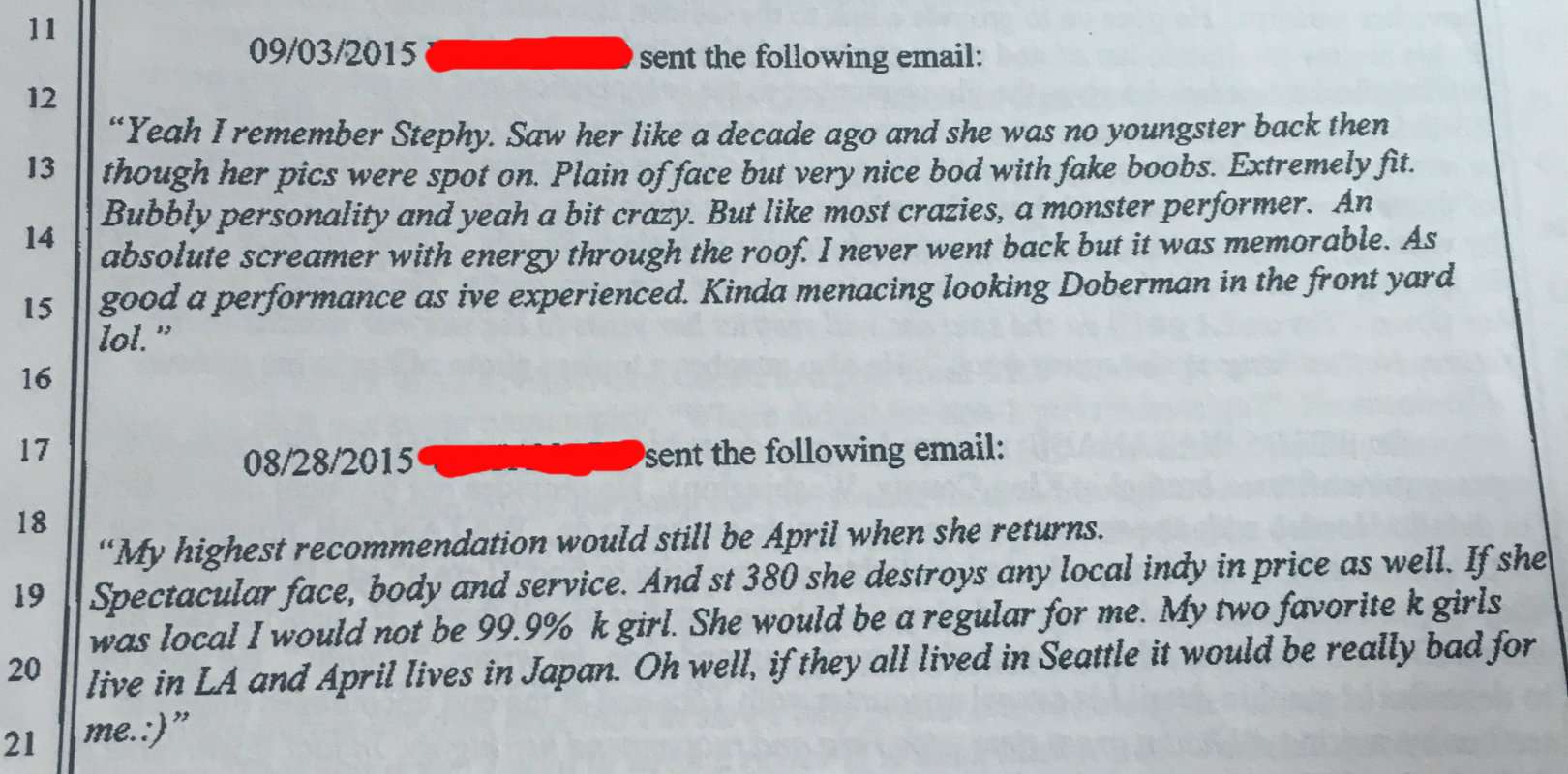

TRB reviews included in police documents further indicate that K-Girls had their own motivations for staying or going. A June 2015 review of "Ace K" says "she will be leaving the 29th… The weather is getting her down ('I'm an LA girl') so she said she will restrict her visits to the warmer months in the future." A TRB post from user "ItsMe" states that he asked "Angel" when she would return to Seattle "and she said she doesn't like this cold, wet weather, so it might be later when the weather gets nicer." A December 2015 email from "Spider Rico" to some other League members claims K-girl "Asuka" told him she didn't like Dallas because it has "bugs the size of dogs. She is slow but wants to stay in Bellevue because it's clean, she said."

Remember that police claim to have thousands of emails, posts, and private communications between those charged to choose from. The few hundred they included in court documents (from which these quotes are drawn) are what they describe as "representative examples." And while there are some reports of new K-Girls saying they are nervous, or seeming to clients like they don't want to be there, such statements are rare.

Police documents also indicate that women who advertised on TRB, including K-Girls, set different prices, had different boundaries, and offered differing levels of sexual activity. For League members, these were limits to be staunchly respected. A "Code of Conduct" states that individuals will be blacklisted if they don't use condoms, take a shower and use mouthwash at the start of each appointment, respect individual boundaries, and remember that no means no.

"Keep in mind she is a professional provider and it is important to recognize that the menu of activities that is offered varies from one provider to another and from one client to another," the code states.

That seems rather gentlemanly—perhaps even feminist?—for a bunch of men who allegedly get off on "abus[ing] these vulnerable young women," as King County Prosecutor Satterberg put it. But the key to painting League members as traffickers and abusers lies in framing all sex workers as victims. If you understand the K-Girls and others who advertised on TRB as individuals with choice and agency, the men who paid them for sex are no more abusers than you or I when we pay someone to watch our kids, listen to us talk about problems, or fix our cars.

Victimless Crimes

If evidence of the kind of human trafficking ring that haunts the public-imagination existed here, detectives shouldn't have had trouble uncovering it. The King County Sheriff's Office (KCSO) had been investigating The Review Board since 2007. An undercover detective first attended a TRB meet-and-greet—meeting both Donald Mueller and the site's proprieter, Sigurds Zitars—in 2008. King County Detective Luke Hillman had been undercover as a hobbyist on TRB since 2013.

Off and on for two years, Hillman would post lengthy and detailed descriptions of alleged sexual encounters with sex workers to TRB. These included the same sorts of statements defendants have been arrested for posting, such as pleas for others to visit a particular woman so she would stick around, info about the screening process for new clients, updates on when a new K-Girl arrived in town, and links to their ads on other websites, like Backpage. (Sample Hillman post: Yoco "is the freight train of sexual energy. … Her last day is August 23rd, RUN, don't walk, to see her.")

For the better part of 2015, detectives interacted undercover with defendants in myriad ways, monitored alleged brothels, and went on more than a dozen "dates" with the women they believed to be forced into "sexual slavery." (Oddly, they felt no need to "rescue" these women at these times.)

Bellevue Police Chief Steve Mylett said at a press conference that the investigation was "unprecedented in size and scope."

Bellevue police had first been alerted to Mueller in April 2015, when a neighbor complained to the agency about possible prostitution activity at an apartment he leased. Soon after, Bellevue Detectives Tor Kraft and Shelby Shearer interviewed Mueller (in an official capacity) and he told them about his business. In the fall, Kraft would meet Durnal while undercover and befriend him; Durnal later complained that Mueller had talked to the cops in the spring and told them "everything." Detective Hillman would also become friendly with Mueller while undercover, and he and Kraft would make dates with women working at both Mueller and Durnal's brothels. In all of these encounters, most involving conversations with detectives posing as prostitution clients, the details of their operations remained the same.

And King County didn't just have their word to go on; detectives also had ample access to suspects' private web-forum and email communications, subpoenaed from internet service providers. Plus they had the 12 women who had allegedly been victimized by defendants—women "held against their will" as "their sexual autonomy [was] stolen repeatedly," as Mylett put it at a press conference. Surely, testimony to that effect from any of the victims would be enough to make human-trafficking charges stick?

But no such testimony exists. To its credit, King County didn't use prostitution charges or immigration threats to try and compel the cooperation of Korean sex workers. Prosecutors don't know what has become of the "rescued" women now.

"Our approach was to allow the women who we recovered from these places to go, without requiring their testimony or requiring them to stay here," says King County Senior Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Val Richey, a leader in the area's crusade against commercial sex. "We were really trying to be very victim-centered by essentially saying, 'This situation is over. We are offering you advocacy or services if you want them; if you don't want them you may go.'"

According to Richey, some of the 12 women they encountered at the apartments did accept an offer to talk with non-government advocates or service providers, but these individuals were not required to report what they heard to police. "We do that very intentionally, so that we can really try to allow some freedom and self-determination for people in this situation," says Richey.

If they had wanted to testify, however? "Absolutely, for those who were interested, we would keep their contact information and so forth," says Richey. But none were interested.

"Many of them I think just wanted to leave."

Deal Me In

Before being arrested on suspicion of sex trafficking, Mueller and Durnal were both frequent sex buyers themselves. Their move to managing commercial-sex businesses had been recent, a natural extension of the relationships they made with sex workers and other clients. Mueller said he started when a woman he patronized regularly, ViVi, asked him to become her booker; from there he became more involved, starting his own agency in late 2014. Durnal still maintained a full-time job as a professional photographer but had begun moonlighting in the sex business after dating a K-Girl himself.

After their arrests last January, both men were held in King County Jail on $150,000 bail. In February, they accepted plea deals, copping guilty to promoting prostitution in the second degree. There was no media blast from King County about this development.

While they're still awaiting final sentencing, the penalties Richey recommended were relatively modest: 60 days in jail for Durnal, who pleaded guilty to two counts of promoting prostitution, and 80 days in jail waived as a first-time offender, plus 30 days of community service, for Mueller, who pleaded guilty to three counts of promoting prostitution. In addition, each man would get 12 months of community custody afterward, pay a $3,000 fine, "be available for interviews and testimony as directed," and take a class on "Stopping Sexual Exploitation."

It's true that severity of crime and severity of punishment aren't always perfectly correlated. Mueller and Durnal might have gotten favorable sentencing recommendations in exchange for offering testimony against bigger prostitution players, for example.

But there's no evidence that's the case so far. Instead, it's likely that the lighter sentences and less severe charges reflect the true nature of these men's actions, which did advance or promote prostitution, but not necessarily at anyone's expense (except perhaps the taxpayers', now that King County has gotten involved).

"If there was evidence that Mueller and Durnal were really like physically restraining or assaulting these women, we would have taken a more aggressive approach," Richey, the King County deputy prosecutor, says. "But instead the evidence was more that [they were] providing a place" and "promoting the prostitution of numerous foreign nationals."

Let's just linger on that a second: For all the bluster about busting up a ring of international bad guys, the worst offenders in the case can only be said to have "provided a place" for consensual prostitution to take place.

Police and media reports were crafted to sound as if the sting took down a massive, coordinated criminal organization devoted to sexual exploitation. In fact, the "brothels" they busted were solo operations that worked more like talent or temp agencies, with willing workers showing up for short-term gigs brokered through the agency. The "sex trafficking website" they took down was a robust platform for independent sex-worker advertising.

And the shadowy sexual exploiters of The League? Just plain-old prostitution clients who occasionally liked to get together for beers.

With Mueller and Durnal out of the picture, it's the sex buyers that prosecutors have been focusing on. But buying sex isn't the crime these defendants were charged with: Like Mueller and Durnal, each faces a felony promoting-prostitution charge. Unlike Mueller and Durnal, however, League members aren't accused of managing escort agencies, operating brothels, or having any direct hand in running a prostitution business. The activity used to sustain their charges includes posting sex stories in online forums, private emailing with and about sex workers, and meeting for drinks at local bars. Part two of this series will explore The League in more depth.

PART TWO: How Washington Police Turned Talking About Prostitution into a Felony Offense

Detectives called it "Operation No Impunity." For years, investigators from the King County Sheriff's Office (KCSO) had been monitoring The Review Board (TRB), a website where Seattle-area sex workers advertised and prostitution clients—or "hobbyists," as they preferred to be called—reviewed their services. The most active reviewers were invited to become part of "The League," a group of men who communicated on a members-only website and held monthly meetups at local bars.

Beginning in June 2015, these meetups were monitored by KCSO, including one undercover detective who had been invited into the group after years of posing as a TRB user. Members would soon find their "hobby" at the center of a national story in which they were cast as human traffickers by law enforcement and media.

"'The League,' the sex trafficking site they frequented and a half dozen brothels in Bellevue were raided and shut down," announced the Bellevue Reporter in January 2016. "Police in the Seattle area…freed a dozen women who were forced into prostitution, arrested 14 people and shut down two websites this week as part of a sex-trafficking investigation," the Associated Press reported in an article syndicated around the U.S.

"King County Sheriff John Urquhart said most or all of the exploited women had been brought to the U.S. from South Korea, where some had been forced into bondage to pay off debts their families owed to criminal organizations," the AP went on. "Eleven men who were arrested were part of an online network that included websites where customers rated the women and posted details to help facilitate the prostitution, he said."

This seedy, sordid narrative hangs on the tack that the women on TRB were unwilling participants in prostitution. That's the only way the site—a marketing venue meets social-network that was highly valued by independent sex workers—becomes a "sex trafficking site," old-fashioned escort-agencies become "human trafficking organizations," and women clearly exhibiting agency in what they're doing become "prostituted persons" and "victims." It's how men whose words display more respect for sex workers than I've even seen from law enforcement get accused of being their oppressors.

And it's how a group of men whose activity consists of nothing more than posting words online can find themselves legally liable for felony crimes and tried in the court of public-opinion for promoting "sexual slavery."

This is the second chapter of a three-part piece exploring this Washington-state "sex trafficking" bust. The first part looked at alleged leaders of the criminal enterprise and how tales of an organized, diabolical, cross-country ring couldn't be more wrong. We'll continue in that vein here, focusing on the men of The League.

'Nobody Pays for Trafficking'

In a January 7, 2016, case summary signed by King County Senior Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Val Richey, "The League" is described as "an exclusive group of men dedicated to the commercial sexual exploitation of women, particularly foreign women brought into the United States for prostitution purposes." The group is accused of running three websites to provide "advice and information about how to access prostituted people in cities across the United States." As a direct result of these activities, wrote Richey, King County has an expanded market "for exploited women" and "a number of Asian brothels have sprung up" in Seattle and nearby Bellevue. The brothels are part of a "national pipeline that transports exploited women around the country for use in prostitution," he claimed.

The case summary against League members described them as "accomplices" who were "engaged in a sophisticated enterprise to promote prostitution" and "maintained constant communication centered on their obsession with sexual exploitation." The women League members are accused of exploiting were allegedly smuggled in from South Korea and forced into sexual servitude.

International news agency Reuters opened an article on the case this way: "A group of Seattle area men has been charged with using adult websites to promote the sex-trafficking of women from South Korea held inside a network of brothels in upscale Seattle area apartments, in a case linked to more than a dozen U.S. states."

"Nobody pays for trafficking," says Richey. "They pay for prostitution. They pay for sex, they're paying for a fantasy."

But as part one of this story showed, such claims range from questionable to outright distortions—something subsequent statements from Richey seem to confirm. While police had heard about potential "debt-bondage-type situations" happening, he says this was far from the case for all or even most of the Korean sex workers his department encountered.

It's "not the same for everybody—whatever brothel or whatever victim," says Richey. "There's a spectrum between somebody who gets on a plane, voluntarily comes over here, wants to engage in prostitution, and does so, and then maybe at one point works in a residence brothel—from that person all the way over to someone whose family is being threatened by organized crime, they offer their daughter to pay that debt off, she's brought over, engages in this to pay off a debt that's never paid off."

During the course of the investigation, undercover detectives made "dates" with more than a dozen different women working at Korean-escort, or "K Girl," agencies. Posing as prostitution clients, the information they gleaned from these women was in keeping with what League members and agency-owners would later say: While K Girls did come to the area expressly to work at Asian brothels, the relationship was more one of independent contractor than indentured servitude.

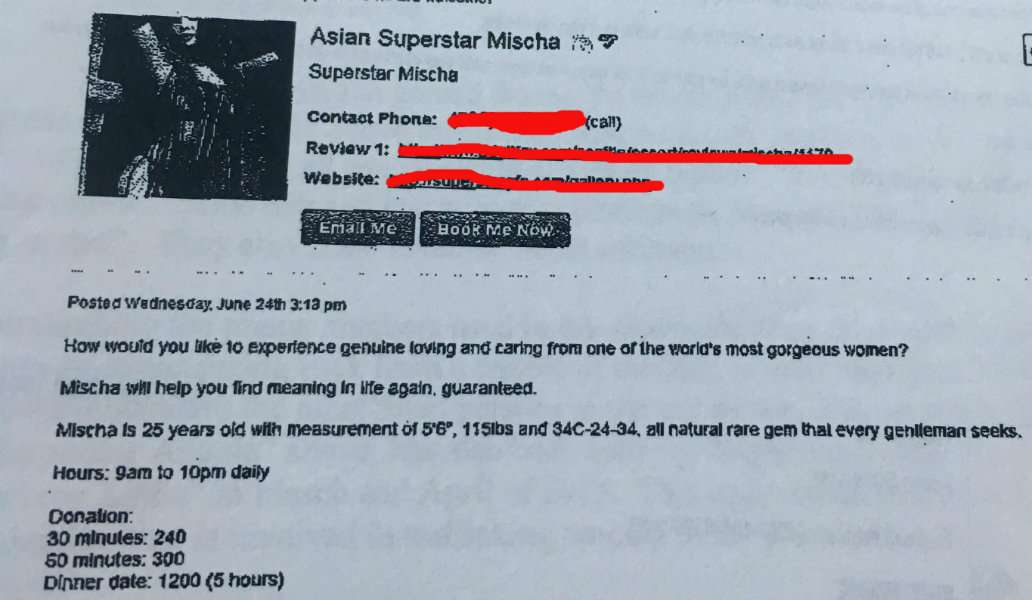

Most of the K Girls charged $300 per hour, of which they kept $200 and turned over $100 to an agency manager. For that fee, the manager marketed the women online, screened new clients, scheduled appointments, fetched supplies such as condoms, and provided a discreet, upscale apartment from which they could live and work. In some cases, agency managers were men—avid prostitution-clients who had gradually gotten pulled into the business side—who spent little time physically present at the places they ran. Other agencies were established by sex workers themselves, who would open spare rooms in their apartments to visiting K Girls.

None of the 12 women discovered during police raids chose to cooperate with the investigation, and police have no idea where they are now. But advertisements and messages posted to sex-work forums indicate that at least some of them may have merely moved on (or back) to selling sex in Los Angeles—anothing fact undercutting their portrayal as helpless victims of human trafficking.

No one disputes that League members did not conceive of themselves as traffickers. "Nobody pays for trafficking," says Richey. "They pay for prostitution. They pay for sex, they're paying for a fantasy." However, he believes the men of The League were "notoriously oblivious to exploitation" happening around them because they simply didn't want to see it.

But countless communications between League members and sex workers that were reproduced in court documents suggest it's law enforcement and prosecutors who are being willfully oblivious.

The League: What It Was and How It Worked

By early June, over a dozen men stood accused of "promoting prostitution" by going to League meetups, messaging one another, and/or posting to TRB.

To understand why the allegations against The League and its members are so novel, it's important to understand just what the group really was and how it worked. The League—or LOEG, as members wrote it, short for "League of Extraordinary Gentlemen"—was essentially a social club and online discussion group, centered on talk about prostitution. At its core was a group of moderately well-off men who unabashedly enjoyed paying for sex and wanted a space to talk about their experiences (and how to avoid law-enforcement detection) without judgment or shame.

"Membership" was extended based on frequency and quality of posts on TRB, according to police reports on the group filed with the King County Superior Court. It entailed access to a password-protected website (TheLoeg.com) for sharing sex stories more privately and invitations to members-only happy hours. These meetups took place at breweries and pubs around Bellevue and Seattle, although many members—including several currently under indictment—never met with other members in person. The main League activity for the bulk of people involved was emailing and messaging each other and posting about alleged sexual encounters online.

The League was free to join, though members were expected to contribute two reviews per month to The Review Board, run since 2002 by retired accountant Sigurds "Tahoe Ted" Zitars and hosted by a web-service company owned by a former sex-worker. Members also vouched for one another to sex workers and escort agencies, something that could be especially valuable for men reaching out to the notoriously stringent-about-screening K Girl agencies.

While discussions among members could, unsurprisingly, be explicit, the group also demanded that sex workers be treated with respect. All League members agreed to a code of conduct that included respecting women's boundaries, never haggling over price, and always wearing condoms. "Regardless of your particular expectations, what is offered is completely up to the provider," it states, warning that any attempt to coax activity after someone says no "is unacceptable" and noting that the women "are encouraged to report continued boundary testing by any client." Later, a section on rough sex and kink advises that "all activities are completely at consent of the girl." The code also reminds hobbyists that even if a session goes poorly, full payment is due; they can choose not to see a particular woman again, but trying to re-negotiate an agreed-upon fee is verboten. And it notes that sex workers appreciate positive reviews on TRB but clients shouldn't "expect or demand" special gratitude in return and must "never threaten a negative review in exchange for particular services."

Operationally, The League was small, with just a few dozen members. Contra news reports describing it as operating "across the United States," the group didn't even operate throughout Washington, let alone around the country—and nowhere in charging documents do police say it did. The only detail that could be twisted into such a claim is that on a few occasions, League members traveling out of town asked others to recommend independent sex workers or escort agencies in their destination cities.

In addition, a few League members were responsible for the website KGirlsDelights.com, an online directory of Korean escorts and agencies. Like TRB and TheLoeg.com, the site was not a profit-making venture. Unlike TRB, there was no component for commentary—KGirlsDelights merely linked out to personal webpages or ads on other review sites, like a Yellow Pages for Korean-American prostitution.

But most of The League's several dozen members had little or nothing to do with the maintenance and operation of either KGirlsDelights or The Review Board. Some members served as moderators on TRB, but it's no more accurate to say that The League as an entity "ran" these websites than it would be to say a kickball team whose members met on Craigslist "run" that classified-ad site now.

Even the police reports confirm that the group's activities were largely benign. In June 2015, after years of undercover posts on TRB, King County Detective Luke Hillman was invited to join The League and first attended an in-person meetup. He would go on to attend four more over the next several months, the last in late October 2015. Hillman describes the content of these meetups as including talking about sexual encounters in "graphic" terms but also discussing "the things they would bring" sex workers, "what kind of food" the K-Girls liked, and "when and how much they tipped."

Hillman's reports also indicate that many League members shunned in-person meetups because they prized anonymity. The five happy hours he went to were attended by less than a dozen men each, and even they only shared their TRB handles with one another. Police determined their real identities by surveilling the meetups and running members' license plates.

Members who didn't attend physical meetings were identified via "personal email accounts seized pursuant to search warrants," Hillman reported in Certifications for Determination of Probable Cause against them. Some members were also identified by subpoenaing records associated with their IP addresses. Google, Microsoft, Comcast, and other entities were all forced to hand over private user data.

Criminally Patronizing a Website

Private emails and messages between League members, obtained by police and included in court documents, make clear that while these men enthusiastically embraced prostitution, they did not want to be patrons of sex-trafficking victims and believed (with good reason) that the women they visited were freely engaged in the sex trade. Occasionally, one would acknowledge that some particular provider wasn't thrilled with the job, but even these instances reveal agency on the part of the women.

For instance, a lengthy review from TRB user "Eash" notes that Thai-agency sex worker "Vicky" didn't seem very engaged or enthusiastic. "She'd worked giving standard massages in Thailand for a while," posts Eash, "but…she had to support her whole family, and so she decided to come to America for a year to do massages with 'extra' because the money is so much better." Eash allegedly asked what she planned to do "when the year is up" and Vicky replied, "I'll stop, and do something else then."

Statements from Zitars, the man who ran TRB, indicate that he frowned on too many Asian sex workers advertising there not because he believed they were being trafficked, but because he believed they attracted law-enforcement attention. According to case summary against Zitars, he complained to undercover King County Detective Mike Garske last fall that President Obama and "the feds" keep giving police money to pursue "human trafficking" that winds up being used against prostitution generally. The government wants to paint all these girls as victims, Zitars told Garske, "when we all know that isn't the case."

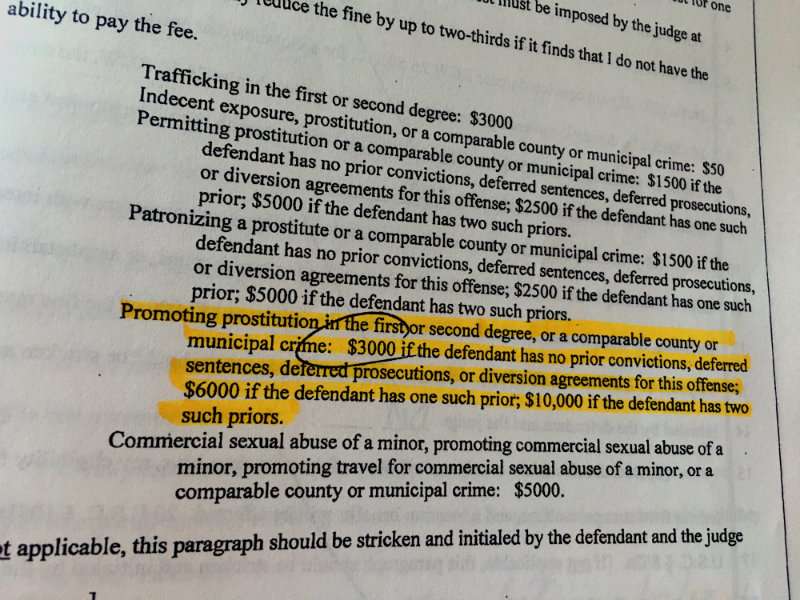

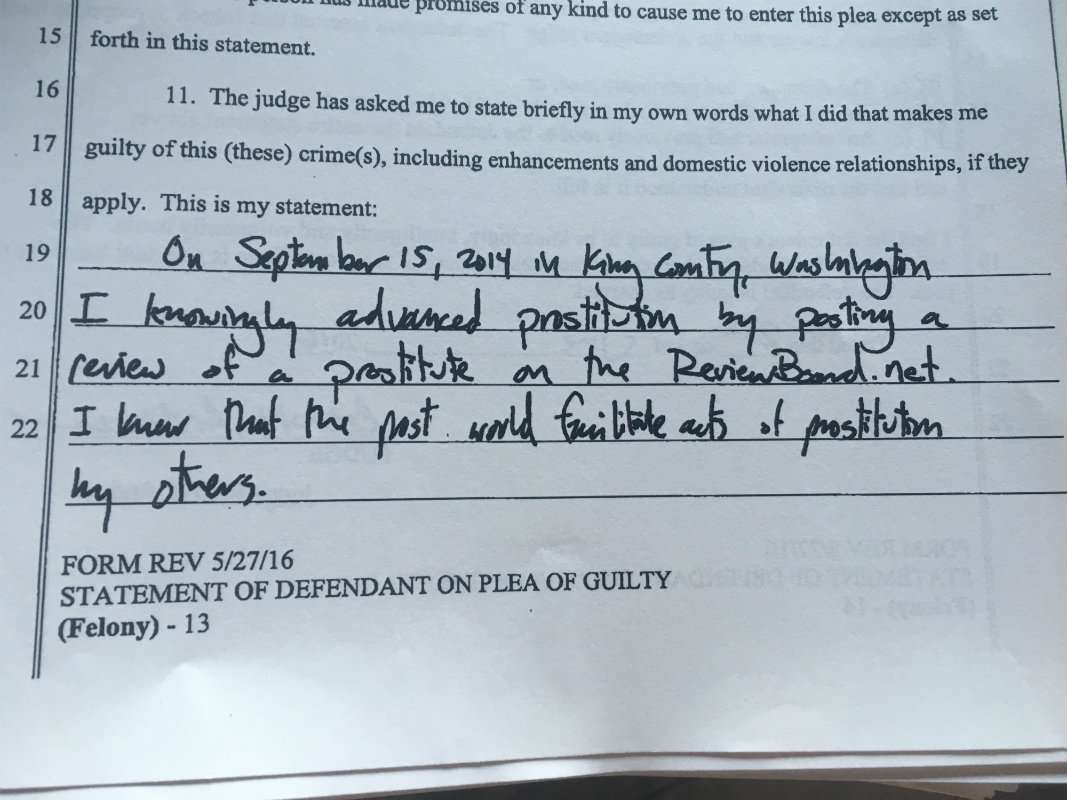

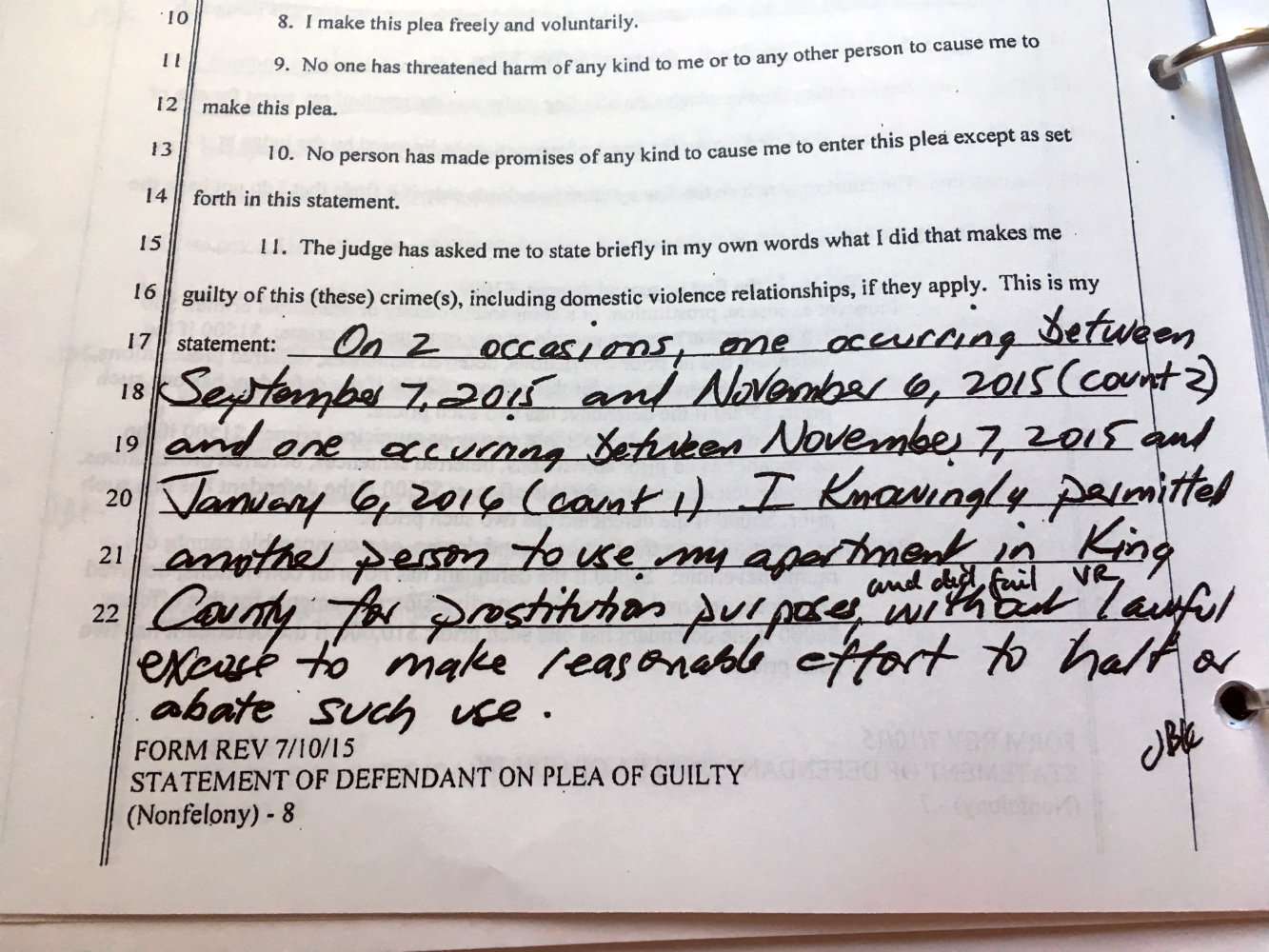

Neither Zitars nor any of the alleged League members were actually charged with human trafficking. (The only two men initially arrested on suspicion of human trafficking eventually copped to a much lesser charge as part of a plea deal.) Nor have they been charged with patronizing a prostitute, the standard (misdemeanor) charge levied against men who solicit sex in Washington. Instead, League members were charged with the more serious charge of promoting prostitution in the second degree, a felony that carries a maximum five-year prison sentence and and a mandatory fine of at least $3,000.

Prosecutors say the men promoted the prostitution of "one or more unidentified individuals" by posting reviews online, commenting on each other's reviews, and emailing with one another about sexual experiences. It's an unusual interpretation of promoting prostitution, a charge generally levied at suspected "pimps," "madams," escort-agency owners, or others who somehow profit directly from the prostitution of a third party. It essentially charges the men with facilitating prostitution for having written stories about sex online.

Todd Maybrown, attorney for defendant Stephen Jenkins, sought further clarification from the county about what he described as the "novel" and "unprecedented" charge his client faces. The state claims that "each defendant is guilty of the felony offense simply because he became a member of the group that is known as The League," Maybrown wrote in an email, adding that he "has been unable to identify any similar prosecution in Washington (or anywhere else in the United States)."

In May, a judge partially granted Maybrown's motion for a "bill of particulars," in which prosecutors explained exactly which part of the promoting-prostitution statute his client was charged under and on what rationale. Shortly thereafter, Maybrown and lawyers of other alleged League members each received a letter from the county.

The case "presented some very unique and unprecedented First Amendment and proof issues," said Zitars' attorney.

The May 26, 2016, correspondence from Senior Deputy Prosecutors Val Richey and Gary Ernsdorff (who currently serves as board president for the Domestic Abuse Women's Network) advised that on June 2, the county would file a motion to amend the charges against all remaining defendants. First, any defendant currently charged with one count of promoting prostitution in the second degree would receive an additional count of the same. More consequentially, the state planned to add "a sexual motivation enhancement on all charged counts for all defendants."

Like hate crime laws—which escalate penalties for an array of offenses, from vandalism to murder, if a perpetrator is alleged to have been motivated by certain types of bias—Washington's sexual motivation enhancement considers crimes of lust more legally serious than crimes committed for other reasons. Prosecutors pointed out that "each sexual motivation enhancement on a Class C felony carries an additional 12 months of straight prison time per allegation that runs consecutively to the underlying" sentence, in addition to adding three years of post-release supervision by the Department of Corrections. "Finally, the enhancement converts any felony into a sex offense which requires sex offender registration," they explained.

Of course, there was one way out: "Alternatively, your client can take advantage of our conservative filing policy and plead guilty to the current number of counts he is facing," Ernsdorff and Richey wrote. Lawyers were encouraged to contact them directly for specifics "on the terms of the plea offer and sentence recommendation for your specific client."

In the month that followed, six defendants, including Zitars and Jenkins, accepted a plea deal.

The case "presented some very unique and unprecedented First Amendment and proof issues that Mr. Zitars looked forward to pursuing at trial," his lawyer, Zach Wagnild, wrote in a sentencing memorandum to the court. "However, during negotiations the State threatened to add Sexual Motivation enhancements to each count due to the fact that his intent [with The Review Board] was not to make money but rather to facilitate further prostitution related activities." Zitars—who cops to running TRB but claims to not have been a part of The League—didn't feel the enhanced sentence was worth the risk, the document stated.

It isn't the first time this year that a plea deal brokered by Ernsdorff raised eyebrows. In March, a 9th Circuit Court of Appeals panel reprimanded the state prosecutor (as well as Wagnild, who served as a King County prosecutor himself from 1998 to 2011) for his role in a 2003 case involving a man named Joshua Frost. Frost now "maintains that the prosecution withheld material, exculpatory evidence" that "would have undermined the testimony of Edward Shaw, a key prosecution witness" who testified in exchange for plea deals on the domestic violence, drug, and unlawful firearm charges he was facing, the court explained.

"We are…troubled by the conduct of Gary Ernsdorff, the deputy prosecuting attorney who handled Shaw's domestic-violence case," wrote appellate Judge Alex Kozinski in an opinion cosigned by four fellow judges. "The sequence of events raises the inference" that Ernsdorff deliberately concealed Shaw's plea deal from Frost, his lawyers, and a jury until a guilty verdict was secured.

The county said these "unsupported accusations" were false.

On August 29, however, Kozinski withdrew the earlier decision.* "In light of the Washington State Bar Association Office of Disciplinary Counsel's dismissal of the grievance against [Wagnild], the previous majority opinion and dissent filed March 21… are withdrawn," stated an order attached to the amended opinion.

Meet Your Modern Slavers

So just who are the alleged men of The League?

Mark Enfield, 58, is the owner of a marketing firm that contracts with military clients. He just joined The League last December and attended his first meeting on the day of its bust. According to the Certification for Determination of Probable Cause against Enfield, his criminal actions include posting 12 reviews on TRB over a seven-year period—reviews with such advice to other men as "treat her like your girlfriend and don't be a dickweed"—as well as emailing with other League members. In the first such email, Enfield writes that he likes paying for sex because he works "a ridiculous number of hours" and spends half of his time away on travel, so time is his "most precious commodity." He has come to prefer K-Girls to other sex workers because he values their punctuality and professionalism.

"I care very much for the girls," Enfield adds. "Sometimes too much."

Enfield is typical of League members, based on court documents. Most come across as caring, decent, and protecting, looking as much for emotional connection as sexual gratification. We can't know how the League members actually treated women during their encounters, but all the available evidence suggests that they were respectful, and interested exclusively in consensual activities.

Noah Jorgenson, 27, is a software developer at Microsoft. The evidence against him, like the others, consists of posts he made to TRB (approximately 44 in 2014–2016) and emails to sex workers and fellow hobbyists. In one private email to the other men, he described his first time paying for sex—in Australia, where it's legal—and how he and the sex worker cuddled and talked all night afterward.

"We shared various stories about our lives, work and traveling," Jorgenson wrote, "and ultimately connected in a way that can be difficult when we have the barriers that most people are accustomed to erecting on a daily basis when we go out into the world."

Stephen Jenkins, 45, was accused of posting 26 reviews to TRB over a two-year period. These reviews (as presented in "representative examples" by police) include tips such as: "If you want a mindless energizer bunny [porn star experience] sex doll, she's not for you. But if you want to be transported for an hour with the girl that you WISH all your ex girlfriends had actually been… Call her now." Jenkins first met undercover Detective Hillman at a July 2015 League meetup, at which time he "suggested that we translate a book on entrepreneurship into Korean and give it to the prostituted persons so they would be more successful" in running their own agencies, according to Hillman's report. [Jenkins claims he never made such a comment to Detective Hillman.]

"I care very much for the girls, sometimes too much."

Neither John Lui, 48, nor Sumit Virmani, 43, attended any League meetups in person. In an intro email to other League members, Lui explains that he is married and loves his wife "dearly," but although she has a "hot body," she "doesn't like or love sex." Emails included in the Certification for Determination of Probable Cause against Lui show him communicating exclusively with independent sex workers, not K-Girls or agencies.

Virmani—director of worldwide health for Microsoft until his recent arrest—had the bad luck of arriving for an appointment just as detectives were busting the place in early January. Virmani's case documents contain an email he sent to League members later that day. After Detective Garske approached, "he told me that I was not under arrest but I was about to go into a crime scene, so they just want my cooperation," wrote Virmani, noting that he could hear "girls crying inside the apartment" as cops entered. He'd never been in a situation like that before, he confided, and he was open with the detective. "Should I be worried that they might use my information for more than what [the officer] said?"

The answer was yes. That spring, Virmani would become one of six men added to the original complaint against League members. On April 7, King County Judge Elizabeth Berns signed a warrant for his arrest.

Police attest that Virmani posted 70 reviews to TRB between 2012 and 2014 and was invited to join The League in April 2015. In detectives' "representative examples" of his digital misconduct, Virmani describes indie sex worker Julia as "a very sensitive and smart person" who is "very easy to have a conversation with." After a visit to K-Girl "Mari," he writes that "she apologized about her limited English as she was using the translator app on her phone a couple of times. Despite the language barrier, I felt a genuine connection with her."

Pricey Punishment

Accused League members have paid dearly for their associations. Even if some are ultimately found innocent, the men arrested as part of this quixotic crusade against prostitution are already—pardon the pun—screwed.

Their names have been printed and broadcast as sex traffickers. Some were immediately let go from their jobs.

Richard Homchick, 50, lost his job as a regional library manager and his board position with a local theater. Initially the only one to plead guilty to promoting prostitution, he later filed a motion to change his plea to not guilty. In the motion, he wrote of being subjected to "sudden and intense media coverage"— local press claimed Homchick was running a "prostitution website" and tied to a "sex-trafficking ring"—and having his life "turned upside down in a very short time."

"I was not dealing very well mentally with the turmoil," wrote Homchick, claiming his original lawyer provided little guidance about the "magnitude" of the charges against him. On August 3, King County Judge Sean P. O'Donnell denied Homchick's request to change his plea.

Faced with the prospect of elevated charges if he didn't, Sigurds Zitars plead guilty on June 30 to three counts of promoting prostitution. As part of the deal, he was sentenced to 90 days of electronic home detention for each count, to be served concurrently, and 12 months in community custody. He must have no contact with other defendants or "persons in prostitution," cover $215 in court costs, and pay a fine of $3,000, 50 percent of which goes to King County law enforcement. While in community custody, he's subject to restrictions on where he can live or travel and must pay "supervision fees" to the Department of Corrections, report regularly to a community corrections officer, submit to regular drug testing, and complete a course on Stopping Sexual Exploitation. He's also indefinitely banned from voting or owning a firearm.

Jenkins also accepted a plea deal, though in his case it was done through what's known as an Alford plea. This type of plea allows a defendant to admit the state's evidence is likely to persuade a judge or jury while still asserting his innocence and without conceding that the state's version of events is correct. As part of the deal, prosecutors recommended that Jenkins be sentenced to 30 days of work/education release (whereby first-time offenders avoid jail by having their wages deposited directly in county coffers for a time), 45 days of electronic home monitoring, or 240 hours of community service.

Mark Yamada, 51, signed a plea deal on June 28, with a recommended penalty of either 30 days in King County jail or 240 hours of community service. In his handwritten statement of guilt, Yamada admits that he "knowingly advanced the prostitution of an individual by posting a review on TheReviewBoard.net. I knew the individual was a prostitute and that the review contributed to her business." That's it.

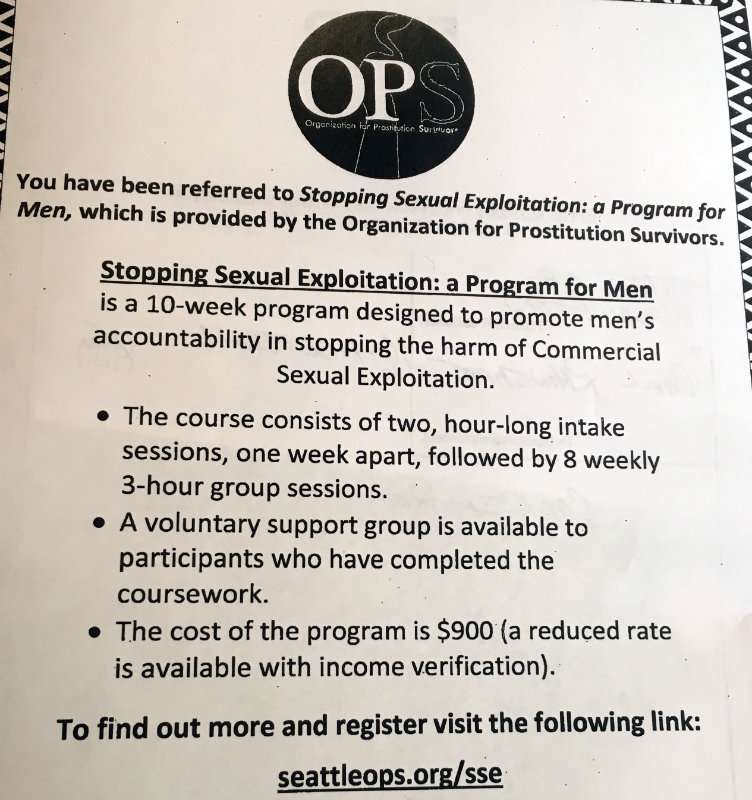

As part of sentencing recommendations, Yamada and Jenkins would each have to contribute $500 to a victim's compensation fund, pay a $3,000 fine, get DNA and HIV testing, and take a 10-week, $900 course at the Organization for Prostitution Survivors. Paul Rhinehart, who admitted to leasing an apartment for sex workers to operate out of in addition to posting reviews, would do the same, with prosecutors also recommending that he be sentenced to six months in jail or work release.

Ideology Over Justice

The way King County has used prostitution charges in this case should alarm anyone who believes in free speech and free association. In the name of stopping sexual exploitation and human trafficking, law enforcement is devoting vast resources to prosecuting men who want to pay consenting adult women for sex—and maybe sometimes talk about it.

As Alison Bass—a journalism professor at West Virginia University and author of the 2015 book about prostitution law, Getting Screwed—wrote on her website about the case in January: "If the American public wants to spend scarce taxpayer dollars to entrap and arrest people for promoting adult prostitution, that's one thing. But it's disingenuous for law enforcement to wrap what they're doing in the guise of sex slavery."

The goal of the court-ordered course is "to deconstruct the toxic masculinity that is at the root of men's sex-buying practices."

The "Stopping Sexual Exploitation" class prosecutors are pushing—so far, Richey and Ernsdorff have recommended it for every male defendant who has accepted a plea deal—is especially troubling.

The 10-week, $900 course cannot be mistaken for run-of-the-mill rehabilitation, the kind of behavioral therapy or psychiatric sessions we might sometimes find unobjectionable as court-ordered restitution. It is run by a nonprofit group called the Organization for Prostitution Survivors (OPS), which was founded "to address the harm of prostitution" and does not differentiate between forced prostitution—i.e., sex trafficking—and paid-sex that adults consent to. The stated goal of the men's course is to "reframe prostitution…as a practice of gender-based violence rather than as a victimless crime" and "to deconstruct the toxic masculinity that is at the root of men's sex-buying practices."

OPS was founded by Noah Gomez, a "prostitution survivor" who went on to earn a bachelor's degree in social justice at Antioch University, and Peter Qualliotine, one of two Seattle members—along with King County prosecutor Val Richey—of the Cities Empowered Against Sexual Exploitation Network. Qualliotine and Richey are also co-leads of a government-funded "sex buyers intervention program" called Buyers Beware.

Qualliotine says the first goal of OPS is providing "services for folks who are in prostitution or getting out of prostitution"—things such as case management, art workshops, yoga classes, drug-dependency counseling, and support groups. "The secondary purpose is to change the social norms that are at the root of this practice of exploitation."

The Stopping Sexual Exploitation course League members must take consists mainly of weekly, three-hour long group sessions that focus on topics like gender inequality and how prostitution is rooted in "men's entitlement." Eighty percent of its attendees are there because of legal mandates, Qualliotine says.

Before co-founding OPS, Qualliotine co-authored a paper with anti sex-work activist Melissa Farley and reportedly described radical feminist Andrea Dworkin—one of the most prominent anti-pornography warriors in the 1970s and '80s—as "the stone of my life…that had an important impact and sent out ripples in all directions." Dworkin's views "are largely mis-characterized in the common culture," he says—a statement that is, in some respects, true. But while people may misquote her as alleging that "all sex is rape," there's no mistaking Dworkin—who's prone to saying there are no such things as prostitutes, only "prostituted women"—on issues like pornography and commercial sex.

Qualliotine is also the former head of a Portland-based program called the Sexual Exploitation Education Project (SEEP), committed to "making men more accountable for the persistence of prostitution." Like OPS, that group had a cooperative agreement with local courts to send men convicted of soliciting prostitution to its programming—a 17-hour, 3-day weekend course. SEEP folded after Multnomah County withdrew its support, citing a desire to start its own program modeled after one in San Francisco (offered as a diversion program rather than a condition of sentencing), according to Qualliotine.

"They were seeing it as more of a criminal issue than a social justice issue," he says. "We see it in a social justice context."

A 2001 analysis of Qualliotine's Portland "john school" compared former participants in a SEEP workshop to men arrested for solicitation who did not do the program and found no significant difference between the recidivism rates in the groups, although recidivism rates among all the men were so low that researchers said no conclusions could be drawn.

But it's hard not to conclude that history is repeating here—or perhaps escalating. King County's case against The League reveals troubling new tactics to "make men more accountable for the persistence of prostitution" and represents a doubling down on what's known as the "end demand" strategy. Drawing on legal models first popularized in Sweden and other Nordic countries, prosecutors claim that because some percentage of people engaged in prostitution will always be underage or forced into the trade, the solution is arresting clients so they'll eventually stop offering to pay for sex.

Ending demand was also a popular rallying cry during '80s drug-war escalation, giving law enforcement motive to focus on drug users rather than just dealers or smugglers. Drugs had harmful effects on individuals and society, the story went, so we needed to deter individual drug use and then, voila, the whole industry would dry up. And to deter individual use, we would make penalties so severe and getting caught so seemingly possible that people would choose to stop using, buying, and selling drugs.

The effect of end-demand ideology in the drug war was to further entrench policy away from harm reduction (i.e., drug-addiction treatment, allowing ways to test illicit-drug quality, etc.) or the prevention and punishment of the worst elements within the drug trade. Every industry, but especially those operating in black markets, will have bad elements. But rather than focusing on those—the people who sell tainted drugs, rip others off, or commit violence or theft in the course of conducting drug business—an end-demand mandate asks cops and prosecutors to see drugs themselves as inherently harmful, and anyone who uses as targets.

A couple of decades later, illegal drugs are more popular than ever in America while prisons are full of people serving lengthy sentences for things like possessing a small amount of marijuana or living with someone who made meth. The history is clear that "end demand" strategies don't work.

Yet here we are now, trying to stamp-out sexual exploitation not by making it easier for victims to come forward, allowing those who choose sex-work to do it safely, or providing services to those at risk. Not by devoting law-enforcement attention to the small proportion of people in the sex trade who rely on violence and fraud. No, instead we're being asked to accept that the exchange of sexual companionship for cash is inherently harmful, even if all parties involved say otherwise. And hence, like the nonviolent drug users before them, people who want to pay consenting adults for erotic play—or maybe just talk about doing so online—must be made into the targets of elaborate, expensive, coordinated sting operations.

In the next section, we'll explore more about who these social crusades are serving. If one thing is clear, it's certainly not sex workers themselves.

*This article has been updated to reflect the court's withdrawal of the March opinion.

PART THREE: From 'Prostituted Woman' to Human Trafficker

Under slightly different circumstances, Jabong Kim might have made headlines as a sympathetic figure. Residing in America illegally, with only a rudimentary grasp of English, the 38-year-old native of South Korea told officials she had come here to flee an abusive marriage, according to a Bellevue Police Department summary of the case against her. Both before and after coming to America in 2013, Kim made a living by selling sex, starting in Japan and then in New York, Atlanta, Las Vegas, and Los Angeles.

After settling in Washington state, she started taking in extra money by renting out spare rooms in her apartment—first in Seattle, then in nearby Bellevue—to other Korean sex workers. This was her undoing. As soon as a sex worker starts helping other sex workers do what they do, they cross a legal line. No longer a "victim" of sexual exploitation, nor merely a person guilty of misdemeanor prostitution, they become culpable for felony sex crimes such as promoting prostitution or even human trafficking. Each of those charges was initially lobbed at Kim.

This may be the way that the American approach to prostitution does the most damage. Sex workers who operate on the streets and all alone—no sharing an apartment, no employing a driver or security guard, no hiring a booker to find and screen clients, no posting to a private web forum where safety tips can be exchanged—can, at worst, be charged with simple prostitution and perhaps loitering, or whatever the local variation of these is called. Both are misdemeanors. And while such charges can be distressing and disruptive, they pale in comparison to the indictments that can await anyone involved in a "prostitution enterprise"—or, as it is more often called these days, a "sex trafficking ring." Under the guise of saving women from sexually exploitative situations, the state inflicts additional pain on sex workers looking out for their own and each other's needs.

That is decidedly not how crusades against "pimps" and "sex traffickers" are sold to the public. In 2012, when Washington's legislature voted to increase the penalties for promoting and patronizing prostitution, Kent Police Chief Ken Thomas said the changes would help law enforcement "reduce the commercial sale of sex" so that "victims of the sex trade can start new lives." Rep. Kevin Parker (R–Spokane), who sponsored the bill to ratchet up potential prison time and fines for those—like Kim—accused of promoting prostitution, said the legislation "sends a firm message to those abusing women and children through prostitution that Washington state will not put up with their criminal behavior any longer."

But much like laws designed to crack down on major drug traffickers wound up used against anyone tangentially associated with the drug trade, statutes purported to punish violent pimps, human traffickers, and sexual abusers end up as cudgels to promote a state's total prohibition on prostitution. That was certainly the result of the major "human trafficking organization" bust Washington police announced in January—at the center of which stood Kim.

Part one of this story described the two men law enforcement painted as masterminds of the "trafficking" organization, who were later revealed to be glorified secretaries and landlords for Seattle-area sex workers. Part two explored the overblown case against an online advertising forum called The Review Board (TRB) and a sex buyers hobbyist group known as "The League." This last section examines Asian sex workers like Kim—known to her clients and colleagues as "Crystal"—and how law enforcement targeted them.

How Many Dates Does It Take to Get to the Center of a Trafficking Ring?

In the spring of 2015, the King County Sheriff's Office (KCSO), the Bellevue Police Department (BPD), and the FBI began a joint investigation into seven Korean escort agencies in the Seattle area: Golden Blossom, K-Dynasty, Asian Haven, KoreanGFE, Special Dream WA, Fantasy K-Girls, and Asian GFE.

In documents filed with the King County Superior Court, KCSO Detective Luke Hillman asserts that "individual prostituted persons are often controlled by an 'agency,'" which sets them up in posh apartments that function like prisons. These women, known in the community as "K-Girls," rarely leave and "are advertised as available twelve to fourteen hours a day, seven days a week," he wrote. The agencies use "bookers" to set up appointments and screen clients.

Bellevue Detective Shelby Shearer was assigned to investigate Kim, who was suspected of running Fantasy K-Girls from an apartment in downtown Bellevue. Throughout the summer of 2015, at least three undercover detectives made several appointments each with women working there, obtaining agreements to have sex for $300 per visit. In some instances, police explicitly state that they left before any sexual activity could take place; in other instances, no such exit is noted. "Regarding our vice investigations, I can tell you that our undercover Detectives do NOT engage in sexual activity as a part of their investigations," BPD Public Information Officer Seth Tyler insists in an email.

The first undercover officer to meet with a woman at Kim's apartment was Bellevue Detective Tor Kraft, who answered ads he found on TRB for K-Girls Yoko and Tera. After Yoko agreed to have sex for $300, Detective Kraft "made an excuse to leave" before anything happened, according to Shearer's case summary. For Tera, Shearer simply noted that "at the end of the appointment with Tara [sic], Detective Kraft was able to obtain Tara's personal cell number."

Later that summer, Kraft made an appointment with Kim—who was also working as a sex worker herself—where he "learned that she was currently working as an independent but admitted to having ties to Yoko and Tera."

In January 2016, Shearer submitted a Certificate for Determination of Probable Cause against Kim. It recommended charging her with prostitution, promoting prostitution, permitting prostitution, money laundering, and human trafficking.

Soon thereafter, police raided Kim's apartment and arrested her. The Seattle Times subsequently described her as the owner of a brothel "where prostituted women from South Korea were forced to work often for 12 hours a day, seven days a week, to pay off debts." The Enumclaw Courier-Herald reported that "brothel owners" such as Kim, Donald Mueller, and Michael Durnal "established a pipeline of foreign women to the Pacific Northwest to meet the burgeoning demand for prostitution fostered by TRB and The League."

But Mueller and Durnal, like Kim, were mostly guilty of providing K-Girls with rooms where they could see clients. TRB was simply an advertising and review forum for escorts—one of dozens like it online, and one valued in the sex-work commnity. And "The League" was just a loosely affiliated group of men who were enthusiastic about visiting sex workers. None of these entities smuggled anyone from overseas.

Permitting Prostitution

The sensational arrest of Kim, Mueller, Durnal, and around a dozen men who patronized their apartments made local, national, and international headlines and TV news segments.

But there was nary a press release or tweet from local law enforcement when three of these cases were resolved. Kim, Mueller, and Durnal, all originally arrested on suspicion of human trafficking, were each offered and accepted plea deals—the two men in February and Kim in early May.

Kim, who has since moved to Los Angeles, pleaded guilty to two counts of misdemeanor "permitting prostitution." At her May 27 sentencing, she received no jail time with the stipulation that she complete 40 hours of community service by January 2017 and agree to the forfeiture of $8,000 in already-seized funds.

As part of her plea agreement, Kim must also submit to a DNA test, pay $200 in court fees, and pay $250 to a victim's restitution fund. In addition, she must complete group support sessions at the Organization for Prostitution Survivors (OPS), a nonprofit that focuses on activities such as yoga, counseling, and art-therapy for "survivors" and classes aimed at changing men's attitudes toward prostitution At one recent OPS art-therapy session, women painted and decorated old high-heels.

The outcomes of these cases should cast doubt on the state's original narrative. If these individuals were really the monsters prosecutors initially made them out to be, why did they get off the hook with a few weeks in jail and some don't-do-prostitution classes? How could law enforcement turn these multi-state villains loose to imprison and victimize vulnerable women elsewhere?

Richey says Kim was "operating a brothel, but it was very low-volume in terms of, like, occasionally another woman would come and work there."

"The investigation demonstrated quite clearly that [Mueller and Durnal were] promoting the prostitution of numerous foreign nationals," says King County Senior Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Val Richey. But even if the places they ran were what "many people would probably describe…as a coercive environment," is that sort of activity "something where we're going to charge a trafficking charge as opposed to promoting prostitution? Probably not."

As for Kim, there was evidence she was "operating a brothel, but it was a very low-volume in terms of, like, occasionally another woman would come and work there," explains Richey. "It just seemed, to our estimation, to be fairly low-scale."

Mistranslating Justice

In Kim's case, the plea offer came soon after her lawyer, Tom Conom, challenged the validity of testimony she gave to police after being arrested. Kim was questioned by Shearer and other authorities, along with someone identified as "FBI translator John Lim."

According to a motion Conom filed with the King County Superior Court in March, Kim's primary language is Korean and her understanding of English is "rudimentary" (an assertion that checks out—texts Kim exchanged with undercover detectives, later reproduced as evidence in police reports, reflect a far from fluent grasp of English). Yet during Kim's questioning by police, the translator hardly translated anything, wrote Conom. A transcript of the interrogation makes clear that "Kim misunderstood many questions" and may not have even understood why she was under arrest.

According to the transcript, Kim's responses during the interview were frequently unintelligible—including when she was asked if she understood her Miranda rights. And when she was asked, in English, whether she would like her rights read with translation, whether she would like to continue the questioning, or whether there was "anything about that you didn't understand," her reply was, "OK, yes."

The officers proceeded with the interrogation. Lim didn't translate the Miranda rights or Shearer's questions. No one sought clarification as to what Kim had intended her "OK, yes" to be a response to.

"If anything," wrote Conom in his motion, "Kim literally responded to the detective that 'yes' she 'didn't understand.'"

But even if the FBI's Lim had been more helpful, Kim's interrogation wouldn't have passed legal muster. The law requires a neutral interpreter to be present, and the FBI was one of the partnering agencies in this investigation.

Villains, Victims, and Whores

It makes little sense to assign one motive to all of the Korean women involved in Seattle's sex business. Unfortunately, we are unable to hear directly from these anonymous women. But what we do know about them—from law enforcement, agency managers, clients, other sex workers, and online clues—suggests some may be sending money back to their families in Korea, some may have school or business plans they're trying to save for, some may actively enjoy the work, some may be indebted to scammers or other coercive individuals, some may be mired in credit-card debt, and some may simply have needed to get out of Korea and, without legal immigration status or great English skills, found prostitution their best or only option here.

"Many women choose sex work not because they love it but because it fits their needs better than other work," noted Christina Slater, a Seattle sex worker who relied on TRB for advertising, in an April blog post. Slater said she met several K-Girls at a TRB meet-and-greet party and they "admitted to coming here with full knowledge…and free will."

In some cases, their range of options might not have been ideal—but they were options. And the option of sticking with sex work was the one that each of them chose, and continued to choose, every day.

Whatever the individual motivations of the women caught up in King County's investigation, or the degree of ambivalence they felt about prostitution, there's nothing indicating they couldn't have fled at any time had they wanted to. They certainly weren't locked in their luxury apartments, forced to fork over money and passports, or prohibited from making decisions about the services they provided. If exploitation was happening, it wasn't at the hands of Donald Mueller, Michael Durnal, or Jabong Kim.

If anything, the K-Girl agencies, "brothels," and bookers allowed migrant sex workers to earn money in the safest and most comfortable way possible. So, too, did the systems set up by The League and The Review Board.

"The Review Board was valuable to a lot of sex workers," said Capri Sunshine, a Seattle-area sex worker and SWOP-Seattle media coordinator, in a January statement. "It was free, undocumented workers without ID or credit cards could use it, and it was where most girls got the majority of their work. [Its closing] has a lot of negative ramifications for sex workers."

For now, there are other online forums for free or low-cost advertising, but law enforcement—in King County and elsewhere—has vowed to shut these down, too. The feds have already taken down at least two major sex-work advertising forums, MyRedbook.com and Rentboy.com, since the start of 2014. Before that, authorities went after the adult-services section of Craigslist and the erotic-ad sections in alt-weekly papers. Most recently, they've turned their attention to a Craigslist-cousin called Backpage.com.

To the most privileged sex workers—those who can host their own websites, rely on an established client list, and so on—this shouldn't prove a huge problem. It's the most vulnerable who will be most harmed by the online forums' absence: those without strong English skills, a valid ID, or credit cards; those just starting out; those who turn to prostitution temporarily to make ends meet, or get away from an abusive relationship or home life. Without sites like TRB, these sex workers will be forced back on to the streets and into all of the danger that picking up clients there entails.

Not only do street-based sex workers lack a way to pre-screen clients or work from locations they know are safe, but it's this prostitution scene that draws the most community outcry (with some good reason). Rather than meeting at hotels, private residences, and other discrete locations throughout a city, sex workers and clients in a street-based system must rendezvous in known prostitution areas, increasing car and foot traffic, scandalizing neighbors, and driving yet more calls to vice police.

Even if online ad forums persist, client crackdowns like King County's create worse conditions for everyone in the sex trade. "Criminalized prohibition makes discrimination and violence possible, and this is a textbook example of how enforcement of laws criminalizing clients and third parties ultimately hurts sex workers the most," said Savannah Sly, dominatrix and president of SWOP's board of directors, in a statement.

League members and TRB patrons were happy to email with sex workers, vouch for one another's authenticity, offer personal information to providers or their bookers for screening purposes, leave evidence of their personalities on the review sites, and visit "brothels" like the one run by Kim instead of insisting on secluded locations. All of this helps keep sex workers safe and reduces the chance that they'll wind up alone with someone like alleged serial killer Neal Falls. But knowing that police are coming after prostitution clients via standard stings and elaborate undercover operations—seizing all sorts of private records and assets in the process—what are the chances future clients will be as willing to take part in such harm-reduction processes?

Prostitution prohibitionists like to pretend this is a good thing, like dedicated sex "hobbyists" will simply drop the habit. But research has shown that the threat of getting caught generally doesn't deter clients. In one recent study out of the U.K., where prostitution is legal under some circumstances, less than one-fifth of clients said a new law criminalizing sex-buyers would keep them from seeing sex workers altogether; most said they would simply be more careful. And when it comes to commercial sex, "careful" means more reluctance about the kinds of measures that help keep everyone engaged in prostitution—whether they want to be there or not—as safe as possible.