The Pill That Supposedly Turns Syrians Into Superhuman, Fearless, Relentless Killers

Captagon captures the imaginations of yellow journalists.

The Washington Post reports that "a tiny, highly addictive pill" known as Captagon is "fueling Syria's war and turning fighters into superhuman soldiers." According to Post reporter Peter Holley, Captagon, a stimulant that is "widely available across the Middle East," not only helps fund various armed groups in Syria; it enables their members to fight without fear, kill without hesitation or remorse, and resist brutal interrogation. "Captagon quickly produces a euphoric intensity in users, allowing Syria's fighters to stay up for days, killing with a numb, reckless abandon," Holley writes. "One secular ex-Syrian fighter who spoke to the BBC said the drug is tailor-made for the battlefield because of its ability to give soldiers superhuman energy and courage."

Holley quotes Reuters quoting "a drug control officer in the central city of Homs" who "observed the effects of Captagon on protesters and fighters held for questioning":

We would beat them, and they wouldn't feel the pain. Many of them would laugh while we were dealing them heavy blows. We would leave the prisoners for about 48 hours without questioning them while the effects of Captagon wore off, and then interrogation would become easier.

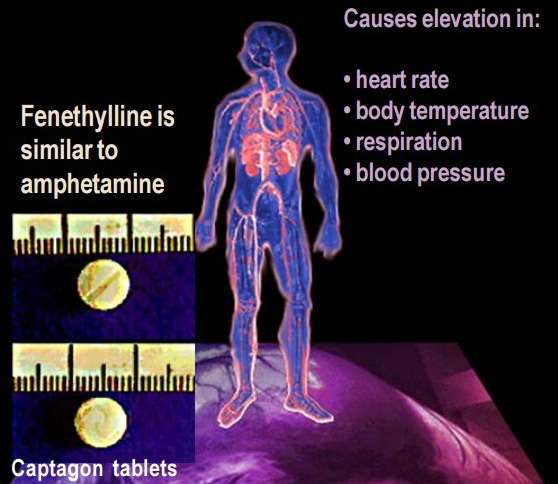

The use of stimulants by soldiers is nothing new. Both German and U.S. forces used amphetamines during World War II, and American pilots continue to rely on them to fight fatigue and maintain alertness. Contrary to the impression left by Holley's breathless report, there is nothing especially magical about Captagon, a.k.a. fenethylline, which is a combination of dextroamphetamine, the main ingredient in Adderall, and theophylline, a stimulant in the same class as caffeine that can be found in tea and chocolate. According to a 2014 post at Smarter Nootropics, fenethyline "doesn't appear to be active in its own right." Rather, "it's a prodrug that the liver separates into both of these compounds." Hence "the effects subjectively would be very similar to taking Adderall XR and drinking tea or coffee," although "the effects are going to be milder than the same dose of Adderall," since "half of the molecule" is the caffeine-like theophylline.

Captagon was first synthesized in 1961 by the German pharmaceutical company Degussa AG, which sold it as a treatment for narcolepsy, depression, and what today would be called attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)—one of the main conditions for which Adderall is prescribed. According to Wikipedia, Captagon "was considered to have fewer side effects and less potential for abuse than amphetamine," which jibes with the Smarter Nootropics account: "It is of lower abuse potential than Amphetamine, and is actually quite comparable to Vyvanse in terms of effects. Essentially while not a nootropic, Captagon was designed to be a 'smart drug' with a lower side effect and abuse potential than Adderall." Yet Holley, citing Reuters, claims "the drug's addictive power led most countries to ban its use."

In 1981 the U.S. government placed fenethylline in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, which is supposedly reserved for drugs that have a high abuse potential but no accepted medical use. "Fenethylline does not have an accepted medical use in the United States and is not approved for distribution," says a 2003 report from the Drug Enforcement Administration. But the DEA also notes that "fenethylline is a central nervous system stimulant with effects similar to amphetamine," which does have accepted medical uses, so this distinction, like many drawn by our drug laws, seems pretty arbitrary. Contrary to what Holley implies, there is no reason to think fenethylline is more addictive than prescription stimulants such as Adderall and Vyvanse or that it is more effective at fortifying soldiers for battle, let alone that it makes them "superhuman."

If Holley had claimed Adderall or Vyvanse was turning Syrian fighters into fearless, remorseless, relentless, pain-impervious killers, his report probably would have elicited more skepticism from his editors and readers. But since Captagon is unfamiliar to the Post's audience, it's safe to uncritically pass on hyperbolic secondhand stories about it. Holley's article reminds me of press coverage from the early 1990s, during the U.S. intervention in Somalia, that blamed the appalling violence in that country on qat, a stimulant shrub with a long history of social use there. Reporters can make up all kinds of shit about other people's drugs with little fear of contradiction.

[Thanks to Claudio Vidal for the tip.]

Show Comments (70)