Senate Judiciary Committee Approves Sentencing Reform in 3-to-1 Vote

A bipartisan consensus produces a bill that's better than reformers feared but worse than they hoped.

Yesterday, by a bipartisan vote of 15 to 5, the Senate Judiciary Committee approved the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act, which would reduce some mandatory minimum penalties and let thousands of current prisoners seek shorter terms. "We have argued for years that our federal mandatory minimum sentencing laws unfairly punish low-level offenders without making the public any safer," said Julie Stewart, president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM). "Today senators from across the political spectrum made it clear that they agree. Today's vote begins the process of undoing these costly and counterproductive laws."

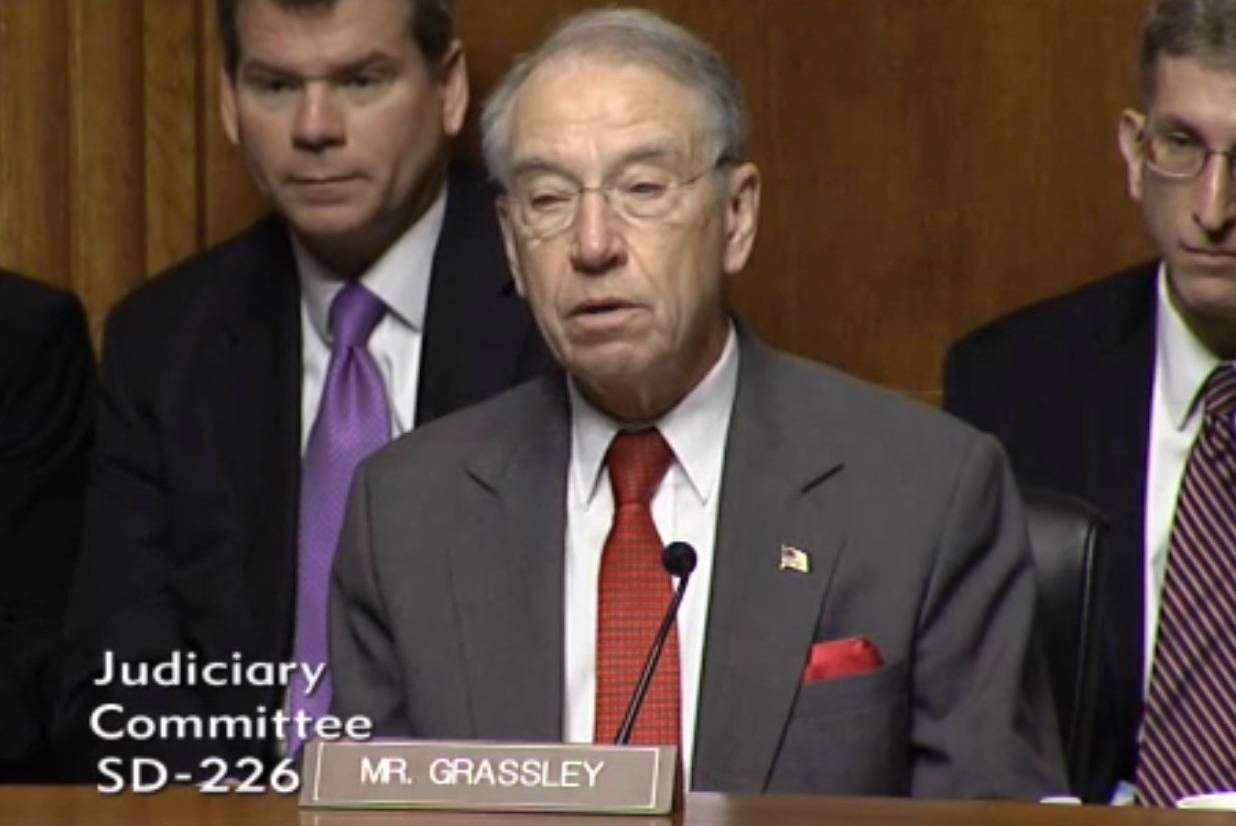

The bill, which was introduced on October 1 by Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), a frequent defender of mandatory minimums, does not go as far as many reformers hoped. But it has a better chance of actually passing than any of the more ambitious bills introduced this year, especially since companion legislation in the House has the backing of Grassley's counterpart there, Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.). And as I've noted, Grassley's bill has the potential to help thousands of current inmates, including crack offenders sentenced to terms that Congress later decided were too long, as well as thousands of future defendants. In many cases the sentence reductions may amount to just a year or two, but for some offenders the bill could shave decades off their time behind bars.

That is nothing to sneeze at, but it is not exactly justice either, especially since we are mainly talking about people convicted of engaging in consensual transactions arbitrarily prohibited by Congress. For "criminals" who have not violated anyone's rights, 10 years is better than 15, but any amount of time behind bars is too much. In that sense, even the most far-reaching sentencing reforms—say, abolishing mandatory minimums altogether, as Sen Rand Paul (R-Ky.) has proposed—would not go far enough. But since it was entirely possible that the current session of Congress would end with no substantial reforms at all, Grassley's bill is better than I feared, although worse than I hoped.

The Marshall Project's Bill Keller, who provides a handy table comparing Grassley's bill with a more ambitious one unveiled in June by Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.), argues that the significance of the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act will depend on what happens next:

The fear of many reformers is that Congress will pass the Grassley bill, declare mission accomplished, and move on. "The defenders of the status quo will say, we've given you reform, now give it time to work," said Pat Nolan, of the American Conservative Union. "It will be the end of federal reform, at least for several years."

Another group of reformers—they would probably call themselves the realists—says the Sensenbrenner bill was never going to go anywhere. "It was the dream list of the defenders," said one reform advocate, referring to defense lawyers who had a hand in drafting it. "It never really had a chance."

The realists, apparently including President Obama, are resigned to the Grassley version as a small step in a new direction. "This is the best that's ever going to come out of a Judiciary Committee chaired by Senator Grassley," said a lawyer who follows the subject closely….The best hope, in the view of the more resigned reformers, is that this modest measure passes, the sky doesn't fall, and reformers have a better chance next time—even as early as next year.

Mary Price, FAMM's general counsel, argues that the transideological consensus reflected in Grassley's bill will have lasting significance. "The mood is changing in this country, and the laws have not caught up with that," she tells Keller. "But the bipartisanship is a remarkable measure of how far we've come. Whatever happens with these bills, I think there is no turning back."

A recent item at Breitbart News, which seems to be part of the shrinking tough-on-crime bloc that views any reduction in penalties as reckless, gives you a sense of the progress reformers have made. Katie McHugh notes that in 2011 Grassley and Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas), who is co-sponsoring his bill, opposed retroactive application of shorter crack sentences, which is a major provision of the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act. The headline: "Grassley, Cornyn Objected to Liberal 'Criminal Justice Reforms' They Are Now Pushing." As recently as last February, Grassley was condemning the Smarter Sentencing Act, a somewhat bolder version of his bill, as "lenient" and "dangerous." Now he is attracting the same sort of criticism.

I don't know whether Grassley had a genuine change of heart or simply figured out which way the wind was blowing. Either way, his shift suggests Price is right in thinking that the politics of this issue have fundamentally changed.

Show Comments (7)