Will 2015 Be the Year the FCC Regulates the Internet Back to 1934?

In June of 1934, the United States passed the Communications Act, a sprawling law regulating the delivery of telephone service and radio communications. It reorganized much of the existing law governing the regulation of radio, telegraph, and telephone service, transferring power to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) from the Federal Radio Commission (which was scrapped) and creating several categories of regulation. Those classified as Title I "information services" would be regulated with a less heavy hand, while those deemed "telecommunications services," a category of utilities dubbed "common carriers," like telephone service, would be subject to stricter rules and oversight.

The passage of the Communications Act of 1934 set the stage for the modern era of communications and telecom regulation, and while it was amended in 1996 by the Telecommunications Act, much of its essential structure remains in place, including the critical distinction between Title I and Title II services.

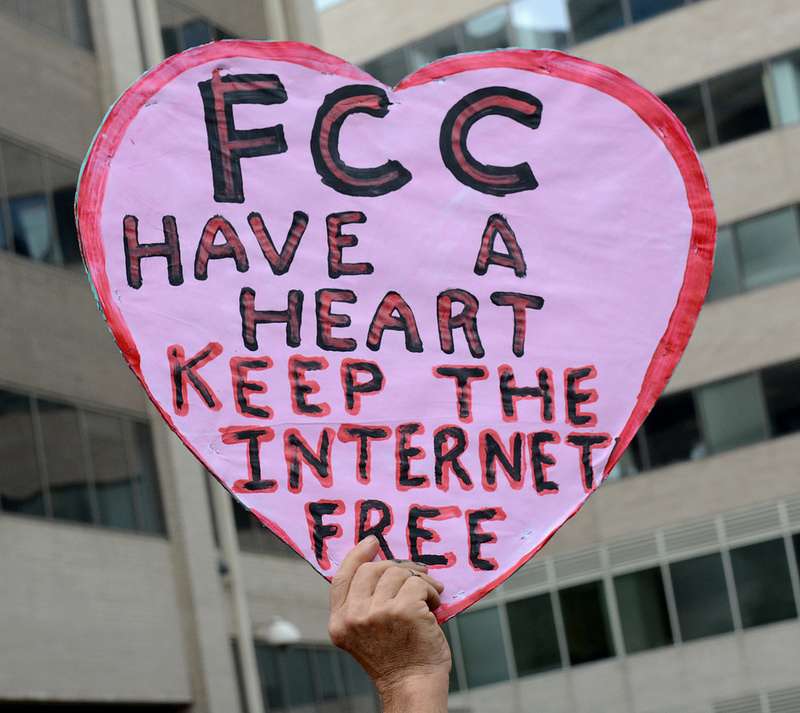

That distinction is at the forefront of the current debate over net neutrality, a regulatory principle which is sometimes vague but which broadly states that Internet infrastructure should be prohibited from discrimination against certain types of information or content.

It's a sometimes-dense, sometimes-abstract policy debate that has raged through multiple administrations and FCC leaders, through multiple high-profile court cases and a seemingly endless number of regulatory proposals and comment periods and responses and arguments over the last few years. It is a policy argument that remains in a perpetual state of flux; something is always on the verge of happening, or something that has happened is on the verge of being taken down. The debate over net neutrality has, over the years, spawned a vast ecosystem of argument, professionalized and organized, one that often seems designed more for self-perpetuation than resolution.

The most recent stage of that argument began when Tom Wheeler was appointed Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission at the end of November 2013. Like his predecessor, Julius Genachowski, he picked up work on net neutrality, a key issue in Obama's first campaign and a priority for many of the administration's young, tech-savvy supporters.

Under Genachowski, the FCC had put in place net neutrality rules at the end of 2010. Those rules were thrown out in court after a drawn-out legal challenge. The FCC, the court said, did not have the statutory authority to impose net neutrality on Internet service providers (ISPs), at least not in the particular way that the FCC had chosen to go about it.

This left Wheeler with two options: Either attempt to establish a modified set of net neutrality rules that might pass a legal challenge, or reclassify broadband internet service from its current status as a Title I "information service" provider to a Title II "telecommunications service"—which would, many advocates hoped, give the FCC far more authority to set rules of the road for the Net.

For the last year or so, then, we've been in a holding pattern, with the FCC releasing a draft proposal of new rules regulating net neutrality, a slew of comments and arguments over those rules, and a related push by liberal advocacy groups and activists urging the FCC to make a big, splashy move and reclassify broadband under Title II. At least initially, Wheeler seemed resistant to the idea, preferring a middle ground proposal he hoped would mostly satisfy net neutrality advocates but not anger the broadband providers who were adamantly opposed to regulation. The providers argued that Title II would stifle innovation, preventing investment in what would essentially be a public utility.

Title II reclassification has, for years, been the big prize many of the most hardcore net neutrality advocates. Only with the stricter regulatory apparatus of Title II, they believed, could the FCC keep broadband providers in check. But until Wheeler arrived, the ideas was never taken very seriously. Moving to Title II would be a complicated, legally fraught process; even backers of a switch tend to agree that applying the full weight of Title II regulations would be too onerous. The FCC, they allowed, would need to rely on "forbearance," a process in which the agency essentially swears off certain regulatory requirements, like, for example, the Title II price controls. The particulars of the forbearance process were likely to be challenged in court however, probably along with the larger Title II switch. A move to Title II was a giant legal landmine. The FCC was trying to avoid the sort of endless legal disputes that had plagued the net neutrality process, not wade in further.

But the Title II advocates gained a significant ally last year when President Obama released a statement urging Wheeler and the rest of the FCC to start the process of reclassification and forbearance. Wheeler is the head of what is technically an independent agency, but he was appointed by the president; the administration couldn't order Wheeler to comply, but its wishes carried great weight.

Which is why it wasn't too surprising to see that, at a speech at the Consumer Electronics Show yesterday, Wheeler strongly hinted that he'll proceed with a move to Title II reclassification.

"We're going to propose rules that say that no blocking, no throttling, [no] paid prioritization, all that list of issues, and that there is a yardstick against which behavior should be measured. And that yardstick is 'just and reasonable,'" Wheeler said, referencing the "just and reasonable" standard required under Title II.

In explaining his thinking, Wheeler said that he was struck by how well the wireless phone industry had flourished under Title II plus forbearance. "For the last 20 years, the wireless industry has been monumentally successful," he said.

But as Jon Healey of the L.A. Times notes, Wheeler's story about the success of the wireless industry left out an important caveat: Wireless data networks were shielded from Title II by the FCC back in 2007—right when wireless data services began to really take off.

There are other potential issues with Title II as well; it might result in as much as $15 billion in tax and fee hikes annually, because it would be subject to local utility levies. And of course it would almost certainly trigger another round, or rounds, of intense litigation.

If Wheeler decides to go forward with reclassification, the proposal will be put to a vote amongst the five FCC commissioners. The outcome is practically predetermined: If Wheeler puts Title II on the table, it's virtually certain it will pass with his vote and the votes of the two other Democratically appointed commissioners. We'll find out which route he takes on February 26, when his proposal is expected and a vote likely to be held.

If Wheeler does take this route, as he now seems to determined, we'll end up with an Internet that is more regulated, more subject to regulatory uncertainty in the near-term, and more like a public utility from another era than an information delivery service for the modern age. It'll be 2015—but for the Internet, it'll be 1934 all over again.

Show Comments (63)