Television Shows Without Television Companies

Amazon joins Netflix in original television series investments

Wikipedia describes House of Cards as a television series, even though it wasn't distributed through any television network, neither broadcast nor cable. The series was distributed to viewers by film-streaming service Netflix in February. Technically, viewers could watch it on their televisions, but because of the online nature of Netflix's streaming service, it's just as likely that many who purchased access to the show saw it on their computers, laptops, or tablets.

The release of House of Cards received a significant amount of press and buzz. The show, a political drama starring Kevin Spacey as a manipulative congressman seeking revenge, is the latest in the growing transition away from typical television distribution of serialized content. Netflix officials claimed House of Cards was its most-watched program soon after its release (though they declined to give actual numbers). Another series, Hemlock Grove, has since launched, and fans of Arrested Development are awaiting Netflix's release of new episodes of the cult comedy (cancelled years ago by Fox) later in May.

Netflix will soon be joined by other contenders in its competition against traditional television networks. Television streaming service Hulu will be launching original shows this summer. YouTube is launching paid subscription channels, which will help finance its own efforts at providing original content.

Amazon is bringing its own spin to producing original television content. Using its own video streaming service, the company has introduced Amazon Original Pilots. Visitors are encouraged to view six pilots for children's shows and eight pilots for comedy series (watch them here). Viewers are then allowed to rate the shows and leave comments. Feedback will help determine which shows will get an order for a full season. The pilots were launched on the site in late April, and according to a company release quickly became the most-watched television videos in their streaming service (Amazon representatives declined to respond to an interview request).

Watching the eight comedy pilots it becomes clear that while innovation may change the way television viewers watch their shows, it has not yet changed the concepts behind television shows. The pilots are all designed to take up the typical 30-minute block, with act breaks for commercials (perhaps Amazon will end up making some shows free to watch with the possibility of advertiser revenue). None of them seize the opportunity to break from the established framework we associate with television productions. As a result, the pilots feel like rejected television network pitches.

Some of them probably deserve to be rejected. The two of most interest (and also the two that pulled in the biggest stars) proved to be rather awful, in this critic's opinion. Browsers is what happens when Glee meets the Huffington Post, and really, that description should be enough to get most folks to turn away. I don't know how they managed to force Bebe Newirth to impersonate a singing Arianna Huffington, but I do hope her kidnappers get long prison terms when they are captured.

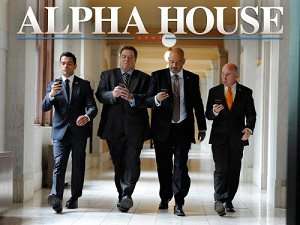

Alpha House, created by Doonesbury's Garry Trudeau and starring John Goodman, starts with an interesting premise: the hijinks of a handful of senators who also happen to be roommates. But the senators are all Republicans, and Trudeau has little to offer but jokes derived from a progressive's anti-conservative talking points checklist. Ultimately, Alpha House underscores the genius of Veep, which plays very close to the vest when it comes to political parties, keeping the conflicts and jokes focused on human interactions viewed through the prism of politics.

Two other pilots have recognizable pedigrees. Zombieland is an attempt to adapt the setting of the movie of the same name into a comic series. The film's original creative team is back, though the original actors are not. The show isn't bad at all, but the zombie apocalypse genre is growing increasingly played out, and the jokes (and scares) are fairly predictable.

The Onion also hopes to increase its reach with Onion News Empire, a parody of a drama about a newsroom that produces what is obviously a parody of news. In typical Onion fashion, the show plays it all seriously, imagining real journalists engaging in traditional research and fieldwork to put together their ridiculous news stories. It's easy to view the show as a takedown of the self-important blowhards of The Newsroom, but the comedy is a bit scattershot (not unusual for a pilot), and Jeffrey Tambor ends up in a bit of a tiresome trope as the older authority figure who is also a closeted pervert.

The two I found the most interesting were actually the two with the least amount of recognition. Those Who Can't is a gleefully misanthropic comedy about a trio of incompetent teachers who are just as bad as their worst students. It's not exactly groundbreaking in its portrayal of witless man-children avoiding real responsibility, but it has a confident inertia to its storytelling and not all the jokes are completely obvious.

Supanatural is an Adult Swim-ish animated comedy (there's also another one, called Dark Minions) that essentially casts Buffy: The Vampire Slayer in a modern mall with a pack of more urban characters. The description actually makes it sound like a mash-up show that is derivative of another mash-up show, but it manages its own tone well. I'll be curious to see how it can maintain variety in future episodes or if it descends into Scooby Doo predictability.

Giving the viewers a chance to rate each series is an interesting experiment that might prevent what is happening with Netflix's new Hemlock Grove, which is getting some less-than-stellar reviews. On the other hand, consider American Idol. The success of singers on the show among voters does not always translate to success in the marketplace. The dynamics might change significantly once consumers are expected to actually pay for their entertainment.

These experiments are good, though. As television consumers turn away from the very tool they used to watch television shows, new systems will be needed to determine what online or mobile consumers are willing to watch and to pay for.

Eventually, we're going to have to figure out what we're going to call "television shows" when we're not associating them with televisions or television companies anymore.

Show Comments (14)