What Mamdani Gets Wrong About the NYC Nurses Strike: State Regulations, Not Greed, Are the Problem

Zohran Mamdani had a chance to pursue health care reform in the New York State Assembly. He didn’t take it.

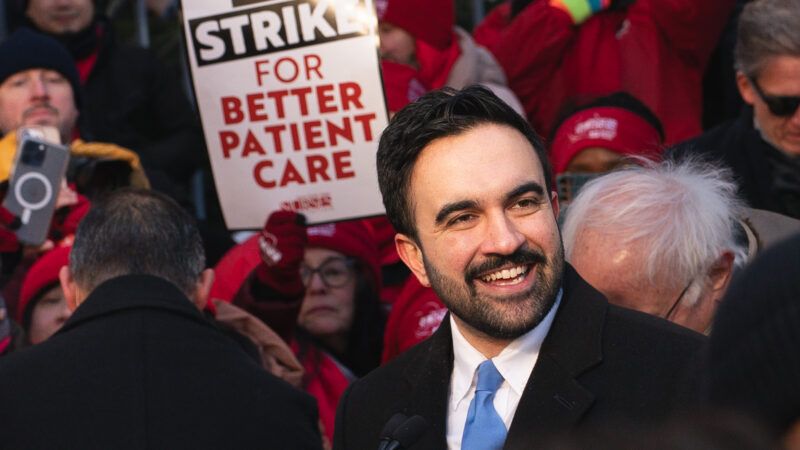

Nearly 15,000 New York City nurses have been striking since January 12, leaving operations at several major private hospitals severely reduced or altogether shuttered. Newly minted Mayor Zohran Mamdani joined the striking nurses on the picket line, blaming wealthy hospital executives for a health care system under strain. But focusing on executive greed misses the deeper cause of the crisis: state policies that restrict competition, limit workforce flexibility, and help create the conditions nurses are protesting.

The strike was called by the New York State Nurses Association (NYSNA), a union representing 42,000 nurses statewide, after contract negotiations with Montefiore, Mount Sinai, and NewYork-Presbyterian medical centers broke down over concerns about low wages, reduced benefits, workplace violence, and staffing shortages.

Union leaders emphasize that patient and provider safety, not compensation alone, is the central issue. Javieer Grewal, an 18-year veteran of NewYork-Presbyterian and a medical step-down vice president on the NYSNA executive committee, says violence in hospitals has worsened in the last few years. "Post-COVID, our society has seen much more violence in this area and it's spilling into the hospital," Grewal says. "Nurses don't have much protection by law."

In December 2025, New York State passed legislation requiring hospitals to develop violence protection programs. Hospitals supported the legislation and have since introduced measures to ensure providers' safety. The NYSNA, however, says hospitals rejected additional safety proposals the union put forward during contract negotiations.

Staffing levels are another point of contention. NYSNA codified safe staffing levels in their previous contracts (in theory, to ensure providers are able to give patients the time and care they need). The union now alleges hospitals have repeatedly failed to meet those standards, leaving nurses overworked. A spokesperson for NewYork-Presbyterian refutes NYSNA's claims, stating that the hospital maintains "the best staffing ratios in the city."

The striking nurses tell a different story. Sophie Boland, a six-year pediatric intensive care unit nurse at NewYork-Presbyterian and a NYSNA executive committee delegate, describes juggling too many high-need patients at once and "the panic you feel when you could possibly miss something that could end someone's life." Jen Lynch, a nurse practitioner of 18 years and an advanced practice delegate for NYSNA, says "hospitals are willing to compromise on patient care to save money."

It was against this backdrop that Mamdani spoke at a NYSNA press conference the morning the strike began. He echoed many of the union's demands and lambasted hospital executives' high wages, arguing that "there is no shortage of wealth in the health care industry."

The mayor is correct on that point: Health care spending represents almost 30 percent of the federal budget, more than any other line item. Yet despite that spending, health care remains unaffordable for many Americans. While Mamdani and the nurses' union place the blame on executive compensation and corporate greed, they overlook the government's role in shaping the very conditions the nurses are protesting.

State-level regulations add layers of bureaucracy that increase health care costs and make it harder for employers to hire. Certificate of need laws allow the state government and incumbent providers to determine what health care facilities are necessary, reducing competition for patients and providers alike. Licensing and scope of practice laws restrict where health care providers can work and what services they may offer, regardless of their training and education. These policies receive little attention in the current debate, but they directly affect the working conditions that nurses are striking over.

During his time in the New York State Assembly, Mamdani did not make concerted efforts to reform these regulations. And in his current role as mayor, Mamdani has little power over health care regulations.

That reality was underscored just three days before the strike started, when Gov. Kathy Hochul, who endorsed Mamdani in his mayoral campaign, issued an executive order declaring a state of emergency and temporarily allowing out-of-state nurses and other health care professionals to practice in the New York City area. This move made it easier for hospitals to recruit nonunion nurses to fill the sudden gap in care and, consequently, undermine the strike.

Much to the disdain of NYSNA members, hospitals are capitalizing on the temporary licensing flexibility, offering up to $9,000 a week to nonunion nurses willing to cross the picket line—nearly triple what union nurses typically earn, according to NYSNA.

While hospitals are not willing to meet the pay demands of NYSNA at this time, they are clearly desperate to increase their roster of nurses. According to Rhonda Middleton-Roaches, an ambulatory care network delegate for NYSNA, hospitals are not accurately portraying the effect the strike is having on their operations. "Out of the 12 clinics, only two are open," she says. "They hired only half of the nurses we had. When they say they are functioning, they are not. They cut services."

Neither party seems willing to make the concessions needed to end the strike. Other than acting as a mouthpiece for the nurses' cause, Mamdani has little ability to influence the outcome. For lasting change, New Yorkers need to look to state policy. But if New York continues along its current legislative path, the health care market is unlikely to become more affordable, competitive, or safer for the nurses on whom it depends.

Show Comments (18)