The Fourth Amendment's Erratic Year at the Supreme Court

The right to be free from unreasonable search and seizure had a rocky 2025.

The right to be free from unreasonable search and seizure had an up-and-down sort of year at the U.S. Supreme Court. Back in May, the Court delivered a 9–0 decision that left civil libertarians cheering for its expansion of constitutional safeguards. But in September, a 6–3 Court left civil libertarians seething over the constitutional wrongs the majority was willing to countenance. Let's review what turned out to be an erratic year in Fourth Amendment law.

First, the good news. In May's Barnes v. Felix, the Supreme Court unanimously rejected a legal standard governing the use of force by law enforcement that, as Justice Elena Kagan's majority opinion put it, told courts to look "only to the circumstances existing at the precise time an officer perceived the threat inducing him to shoot."

That approach "improperly narrow[ed] the requisite Fourth Amendment analysis," Kagan held. "To assess whether an officer acted reasonably in using force, a court must consider all the relevant circumstances, including facts and events leading up to the climactic moment."

The facts and events leading up to an officer's split-second decision to use force may include many pieces of relevant information, including whether the officer's own poor judgment or improper tactics helped to foster (or to create) the deadly situation. Yet the "moment of threat" rule told the courts to pay no heed to such important info. By rejecting this rule, the Supreme Court ensured that law enforcement would be governed by a more robust Fourth Amendment standard. It was a good day for civil liberties.

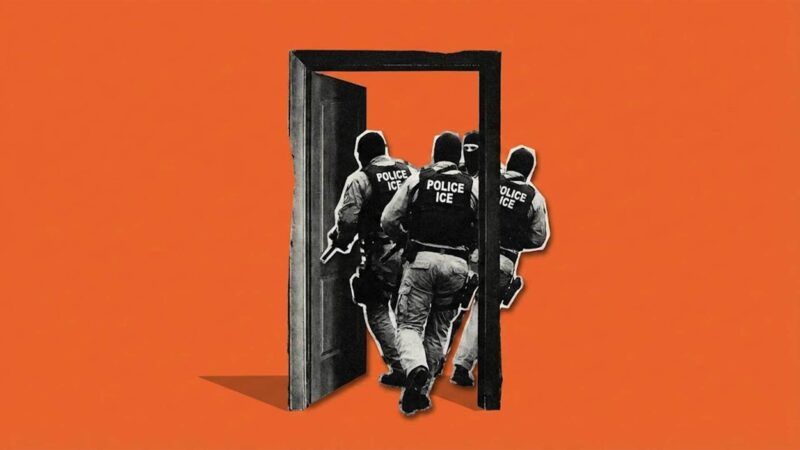

Now for the bad news. In September's Noem v. Perdomo, the Supreme Court lifted a lower court order that had blocked the Trump administration from employing "likely" unconstitutional tactics as part of its roving immigration crackdowns.

According to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, federal immigration officials likely violated the Fourth Amendment rights of multiple U.S. citizens in the greater Los Angeles area by seizing them based solely on such illegal factors as their "apparent race or ethnicity," or the fact that they were "speaking Spanish or speaking English with an accent."

But the Supreme Court, in an unsigned emergency order that offered no legal rationale, lifted the block and allowed the Trump administration to resume such tactics. Justices Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Ketanji Brown Jackson dissented from that order.

Only one of the six justices who favored the order actually explained why. Writing in concurrence, Justice Brett Kavanaugh asserted that such racial profiling by immigration agents deserved a judicial green light because it is "common sense" to seize people based on "relevant factors" such as their "apparent ethnicity" or that they "gather in certain locations to seek daily work."

To make matters worse, Kavanaugh was apparently untroubled by the obvious threat such tactics posed for those U.S. citizens who were ensnared in the dragnet based on their "apparent ethnicity." "As for stops of those individuals who are legally in the country, the questioning in those circumstances is typically brief," Kavanaugh asserted, "and those individuals may promptly go free after making clear to the immigration officers that they are U.S. citizens or otherwise legally in the United States."

The facts on the ground contradict Kavanaugh's breezy assertions. For example, as Reason's Autumn Billings has reported, a U.S. citizen and Iraq War veteran named George Retes "was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and other federal agencies for three days and nights despite telling officers he was an American citizen and his identification was in his nearby car." Similarly, as Reason's C.J. Ciaramella has detailed, the Alabama construction worker Leo Garcia "is challenging the Trump administration's warrantless construction site raids after he says he was arrested and detained by federal immigration agents—twice—despite being a U.S. citizen with a valid ID in his pocket."

So much for harmless "brief" encounters from which citizens "may promptly go free." These "Kavanaugh stops," as some critics have taken to calling them, illustrate the utter disregard that Kavanaugh and some of his colleagues have shown for the right to be free from unreasonable search and seizure regardless of skin color.

Let's hope the new year brings gladder tidings for the Fourth Amendment.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"But the Supreme Court, in an unsigned emergency order that offered no legal rationale, lifted the block and allowed the Trump administration to resume such tactics. Justices Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Ketanji Brown Jackson dissented from that order."

Offering no legal rationale is the norm in such orders where a final SCOTUS hearing and subsequent ruling is pending. The fact that Kagan, Sotomayor and Jackson are the only justices who dissented is indication that the ruling is correct. Root needs to stop being salty about SCOTUS blocking radical judges from imposing their policy preferences on the country.

More likely he has a vanity photo of Boasberg as his screensaver.

"We *the People* of the United States"

"The right of *the people* to be secure in their persons"

"the privileges or immunities of *citizens* of the United States"

Sorry. I'm just not seeing the part where *foreign people* who break-into your nation are granted "the People of the United States" ... "privileges or immunities of citizens"

Perhaps you should try again with 1st Amendment and how a FAT-MOUTH grants a 'right' to invade another nation.

Maybe you'd like to make a case where nobody can shoot an armed-robber who broke-into their house too huh? Because the illegal 'criminal' had 2A rights.

You can't have a fourth amendment without the first.

You can't have a first amendment without the second.

There is a logical sequence to the attacks on freedoms "guaranteed" by the bill of rights.

US citizens are detained somewhere every minute of every day in circumstances that have nothing to do with immigration enforcement. That encounter can be brief or extended. These detentions are not in and of themselves 4th amendment violations. Every time a cop pulls a motorist over and demands their credentials that individual is detained. But in the case of immigration enforcement ordinary police actions based upon reasonable suspicion suddenly become an agregious violation. Are errors made? Of course. But you don't have to look very hard to find individuals begging to be detained by ICE. Much ado about very little in the larger context.

Reasonable suspicion still requires reasonable suspicion of a 'crime.' Many immigration violations are civil in nature. Hence, even being the darkest brown is not, without more, reasonable suspicion of criminal activity. Being brown and speaking with an accent or Spanish doesn't change that outcome.

To any non-excuse maker the very 'MASS' of the 'crime' spree allows some leeway. There is reasonable suspicion based on attire when a same-dressed "flash rob" occurs. The only difference today is the 'non-white' have been SOOOOO EXTRAVAGENTLY painted as the *special* people they are above common-sense law. (i.e. The Race-Card dismissal)

Not that you would know because you appear to try to live in an alternate reality, but SCOTUS already decided you are WRONG.

".... because it is 'common sense' to seize people based on 'relevant factors' such as their 'apparent ethnicity' or that they 'gather in certain locations to seek daily work.'.

Objection.

Our rights are supposed to protect from unreasonable intrusion.

The ability to modify one's appearance to look or sound like a suspect is not a breach of law, notwithstanding that speaking freely in presence of police can lead to trouble with law.

The founders probably had little idea that their neighbors from Meh-hi-co and on would be treated like they have to evacuate. Although the allusion Article I, Section 9 "The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall now think freely to admit ...." can implicitly be prohibited by Congress prior to the year 1808. You might feel like the period leading up to the Civil War missed the boat. There was possibly no one reassuring the South that they would have to transition out of slavery in favor of a timely leadership directive to recognize the rights of slaves and respect them as subject to the laws of the republic rather than to the laws of dog & domesticated animal owners willing to chain up their good children, wives or neighbor when occasion doeth demand.

Conservatives like wasting resources in the name of justice. Big rules and draws a lot of attention to their obvious importance as elected leaders who do such big things.

The infrastructure is not founded on mass repatriation but rather upon punishment for crimes. Existing is not a crime except obviously within Russia's reach. The founders were unconcerned that a government founded with rights of people in mind would be sending people to a designated home without having committed a real crime -- a felony, in other words.

We get the idea that you are not supposed to enter America without surrendering to the border police. But we should notably add on, "unless you are not guilty of any crime nor wrongdoing." Because if no one's looking for you (as a wrongdoer), then -- rationally -- why should you exist in any forensic/interesting manner?

To make that move further away from pluralism in getting specific with something of a "one wrongdoer, one trial" ideal that I know is not always necessarily most practical, police should be getting specific with whom they have in mind to arrest rather than invent excuses and call them common sense as if because Henry Ford ran a most efficient assembly line, that the police can simply add that to their wish list for the supreme court to requisition for them, as well, to engage mass arrest when there is no pressing public danger to warrant mass arrest.

Punishing people for entering the country the wrong way should be considered a waste of funding unless they can be arrested there on location where America can show that the punishment to be real and effective and not an afterthought. Arrest them at the border like an effective LEO operation rather than like a sieve that inconveniences all the people who belong.

And really, any belong as guest or visitor or trader unless they have a criminal charge against them that has not been settled or cannot claim a legitimate interest in remaining in the states.

Designating a person to be an illegal alien amounts to a bill of attainder, pure and simple. Their existence alone does not make them a citizen, however.

Claiming a nationality would be the protective resort of a person who has no legitimate business to claim. Sending a person to another nation who has no legitimate business in the states to claim would be a sensical move. But arresting people for looking or sounding like they are too stupid to have citizenship should be foregone in favor of real police work.

If what you say is right; You're really saying what Trump is doing is ALL Biden's Fault for NOT defending the nation and you're 100% correct whether you recognize what you're really saying or not.

Just because of mob of bank robbers aren't stopped at the door doesn't mean nothing can be done once inside under some silly BS excuse that one of the tellers might be investigated.

Moribund!

Like the 10th Amendment, the 4th Amendment is dying if not dead. In 1789, the Federalists won the day with the ratification of our original constitution. As the Anti-Federalist argued, that constitution would lead only to an accretion of power by an increasingly powerful and tyrannical, central government. Even there, an accretion of power by an imperial presidency has occurred. Consequence? Decline of the nation and tyranny upon its citizens.

“An error lurking in the roots of a system of thought does not become truth simply by being evolved.” -John Frederick Peifer (c. 1960)

For these United States to regain status as a nation and freedom for its citizens, we must rewrite the Constitution by including Science as described in detail in the novel, Retribution Fever. The Constitution must adhere to the guidelines of the Scientific Method (specificity, objectivity, and accountability). It also must adhere to the laws of Nature via the principles of Biobehavioral Science. To do otherwise is to invite disaster as we now are witnessing.

“Some men look at constitutions with sanctimonious reverence and deem them like the ark of the covenant, too sacred to be touched.”-Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826)