Yes, the First Amendment Applies to Non-Citizens Present in the United States

A conservative federal judge questions the reach of free speech.

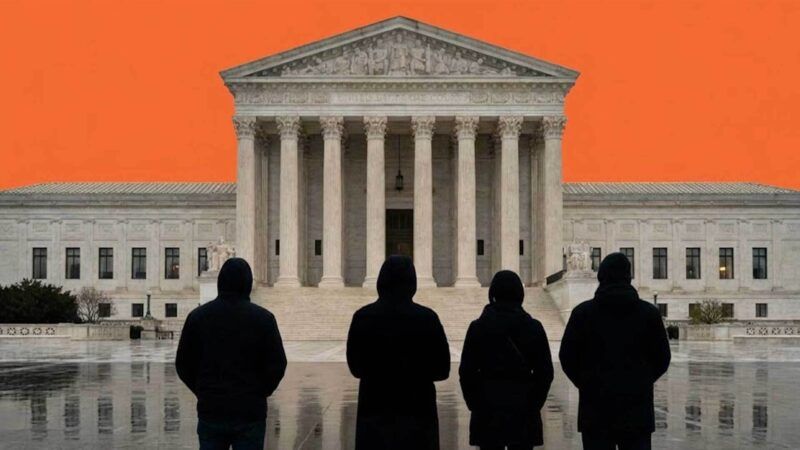

The First Amendment says that "Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech." But one prominent conservative judge, whose name has been mentioned as a possible U.S. Supreme Court nominee by President Donald Trump, thinks that protection against government censorship may not apply to non-citizens who are present in the United States.

Is the judge right?

You’re reading Injustice System from Damon Root and Reason. Get more of Damon’s commentary on constitutional law and American history.

Writing for himself in the recent case of United States v. Escobar-Temal, Judge Amul Thapar of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit asserted that "neither history nor precedent indicates that the First Amendment definitively applies to aliens."

Yet in Bridges v. Wilson (1945), the Supreme Court unambiguously stated that "freedom of speech and of press is accorded aliens residing in this country." That case centered on an Australian immigrant and labor union activist named Harry Bridges. He faced deportation because of his alleged "affiliation" with the Communist Party. "It is clear that Congress desired to have the country rid of those aliens who embraced the political faith of force and violence," the Court said. But "the literature published by" Bridges and "the utterances made by him," the ruling noted, revealed only "a militant advocacy of the cause of trade-unionism" and "did not teach or advocate or advise the subversive conduct condemned by the statute." The otherwise lawful speech of this non-citizen was thus "entitled to that [First Amendment] protection."

Thapar's appeal to history is also suspect. "The application of the Alien and Sedition Acts to resident foreigners," Thapar claimed, "suggests that the founders did not understand the First Amendment to extend to aliens."

The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 are not normally cited favorably when freedom of speech is being discussed. And with good reason. The Sedition Act notoriously made it a crime, punishable "by imprisonment not exceeding two years," to write, print, utter, or publish "false, scandalous and malicious" statements with the intention of bringing the federal government, members of Congress, or the president, "into contempt or disrepute." This censorial statute applied equally to citizen and non-citizen.

The Federalist administration of President John Adams promptly used the Alien and Sedition Acts to punish its political enemies, including by securing the imprisonment of several journalists. A number of American citizens were thus locked behind bars for the supposed crime of criticizing their own government.

James Madison detailed the many constitutional defects of the Alien and Sedition Acts in his "Report of 1800." As Madison pointed out, "the power over the press exercised by the sedition act, is positively forbidden by one of the amendments to the constitution." Madison was of course referring to the First Amendment.

In other words, if Thapar is correct that the mere existence of the Alien and Sedition Acts provides evidence of what the founders thought the First Amendment allowed the government to do, then it would follow that the founders thought the First Amendment allowed the government to criminalize the political speech of citizens who criticized the U.S. government.

Yet Madison, a principal architect of the Constitution and rather prominent founder himself, denounced the Alien and Sedition Acts as a constitutional monstrosity. To say the least, Madison did not think that such hated laws offered any reliable guidance as to what the Constitution meant or should mean.

One last point about Thapar's misguided opinion: He failed to grapple with the fact that eliminating freedom of speech for non-citizens necessarily means that citizens will suffer free speech harms, too. As Frederick Douglass put it, "to suppress free speech is a double wrong. It violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker." If a green card holder stands on a soapbox in a public park in a U.S. city and criticizes the actions of the federal government, American citizens who wish to hear that person speak have a right to do so without government infringement.

Contra Thapar, the First Amendment protects both sides of what Douglass memorably called the "right to speak and hear."

Show Comments (81)