SCOTUS Probably Won't Put Any New Limits on Warrantless Home Searches

The Supreme Court heard oral arguments this week about the "emergency aid exception" to the Fourth Amendment.

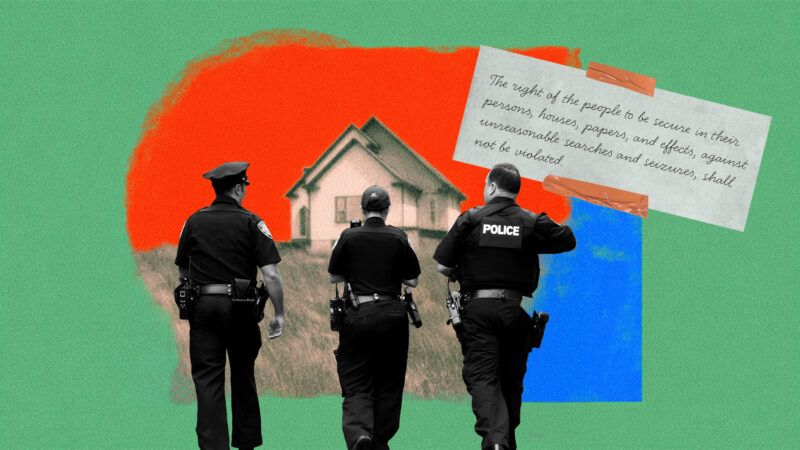

The Fourth Amendment protects "the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures." When it comes to a person's home, that generally means that the police may not enter without a warrant.

But what if there might be an emergency occurring inside the home? Yesterday, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a far-reaching case that centers on what is called the "emergency aid exception" to the Fourth Amendment.

You’re reading Injustice System from Damon Root and Reason. Get more of Damon’s commentary on constitutional law and American history.

This case, known as Case v. Montana, presented the following question to the justices: "whether law enforcement may enter a home without a search warrant based on less than probable cause that an emergency is occurring, or whether the emergency-aid exception requires probable cause." In other words, should the actions of the police be governed by the stricter standard of probable cause or by the more lenient standard of reasonable suspicion? How much leeway should the cops get?

Judging by the tenor of yesterday's oral arguments, a majority of the Supreme Court seemed uncomfortable with the idea of imposing the stricter probable cause standard on the police in potential emergency cases. If that view ultimately carries the day, it would be unwelcome news for Fourth Amendment advocates, who would like to see the actions of the police controlled by the stricter standard.

At the same time, however, a majority of the Supreme Court also seemed uncomfortable with the idea of allowing the more lenient reasonable suspicion standard to win, which would be welcome news for Fourth Amendment advocates.

A third possible outcome also emerged during the arguments.

Multiple justices pointed to the Supreme Court's 2005 ruling in Brigham City v. Stuart, which said that "police may enter a home without a warrant when they have an objectively reasonable basis for believing that an occupant is seriously injured or imminently threatened with such injury." Those justices suggested that the "objectively reasonable basis" standard is actually the one that the police should have to follow in all such possible emergency situations, and that the present case should be remanded back down to the Montana Supreme Court, which should be told to go back to the drawing board and follow that ruling too.

Of course, if the Supreme Court does adopt this anticlimactic third approach, it risks raising many more questions than it answers. For example, is having an "objectively reasonable basis for believing" that an emergency is occurring the same thing as having probable cause to believe that an emergency is occurring? Or is it the same thing as having reasonable suspicion to believe that an emergency is occurring? Or does the Brigham City test perhaps represent some kind of intermediate standard that falls somewhere between probable cause and reasonable suspicion?

Even if the Supreme Court does decide to effectively punt on this case, the Fourth Amendment questions arising from the "emergency aid exception" are not going away.

Show Comments (29)