Yes, Tariffs Are Raising Prices

And if Trump moves ahead with his threatened August 1 tariff hikes, prices will climb even more.

In an interview with Fox News on Sunday, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick bragged about the "amazing" revenue that the Trump administration's tariffs are delivering to the U.S. Treasury.

"The tariff revenues are amazing: $700 billion a year," Lutnick told Shannon Bream. "That's just net new money the government never had before. You take that for 10 years, that's $7 trillion."

Ignore, if you can, the still bizarre (but increasingly common) sight of a Republican executive official bragging about how much money the federal government has extracted from the economy. Similarly, try to ignore Lutnick's questionable calculation of how much revenue the tariffs will generate—the best estimates right now suggest they will generate between $2.5 trillion and $2.7 trillion over the next decade, not the $7 trillion that Lutnick claims. (But those estimates are tricky things, given the lack of certainty surrounding all of this.)

Focus instead on the obvious question that Lutnick's claim ought to bring to mind: Where, exactly, is all that "new money" coming from?

All taxes are paid by someone, and President Donald Trump's tariffs are no exception to that rule. The question of who pays and in what amounts is likely to become even more of a focal point in the coming days and weeks, as the White House follows through on its threat to hit imports from dozens of countries with higher tariffs starting on August 1.

Economic data from the past few months, during which the Trump administration hiked tariffs on goods from Mexico, Canada, China, and elsewhere, provide a preview of what's to come after the August 1 tariffs hit: Higher prices for Americans.

That is, of course, what economists say tariffs do. Raising prices is really the only function of a tariff—which artificially inflates the price of imported goods to make them less attractive than domestic alternatives. Economists will also tell you that's not the whole story. They say that domestic producers often raise prices as well, since imported competing goods are now more expensive. They also say that tariffs on raw materials and intermediate parts—like the Trump administration's levies on steel, aluminum, and the parts necessary to build a car—will push up the cost of building other, more complex goods, and those higher costs will be passed along to consumers in the form of higher prices.

The impact from tariffs won't show up in the same way as an income tax or property tax does. It will not be a lump sum or an amount that is removed from your paycheck in a predictable and orderly way. Instead, the estimated $2,400 that the average American household will pay in tariff costs will be siphoned away in dribs and drabs, in higher prices scattered throughout the economy.

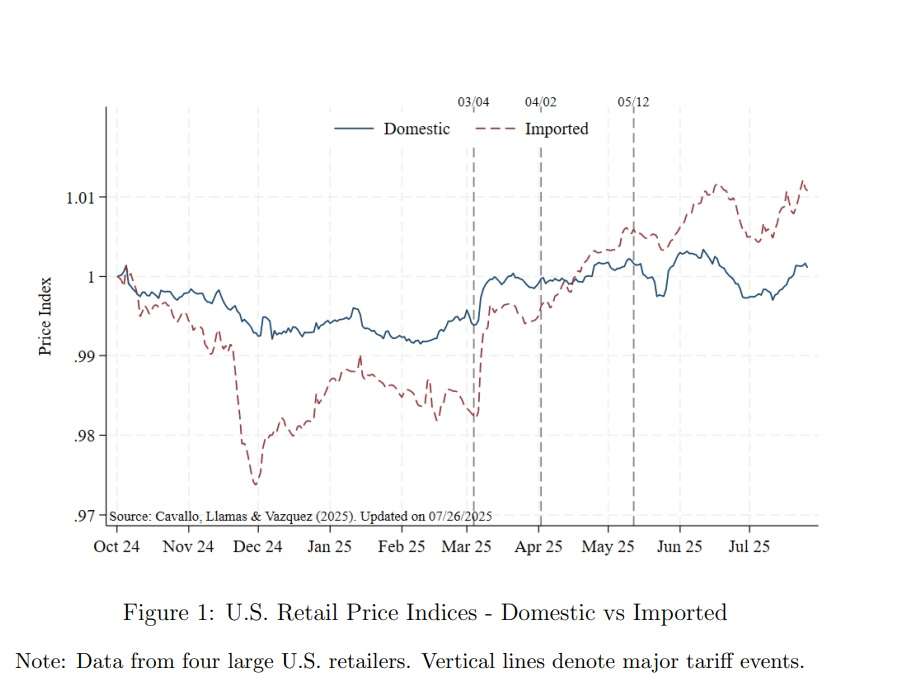

There have been "relatively quick price responses to tariff announcements," report a group of economists connected to the Harvard Business School's Pricing Lab, which tracks prices throughout the economy. In a paper updated earlier this month, the Harvard economists report that there's been a "cumulative increase in imported goods prices since early March" of approximately 3 percent. The paper relies on data from four major U.S. retail chains.

Their data show that prices for both imported and domestic goods have climbed since Trump took office, with foreign-made goods increasing more quickly thanks to two noticeable leaps that occurred right after Trump's tariff announcements in early March and early April.

"Sorry, there is no tariff free lunch," is how that study was summarized by Unleash Prosperity, a newsletter run by Stephen Moore, a former Trump administration economic adviser.

The tariffs set to go into effect on August 1 are significantly larger than everything that has come before. They will impact goods from over a dozen countries with import taxes as high as 50 percent—and the consequences may be more widespread than what's been detected so far.

Groceries, for example, could take the brunt of the August 1 tariffs. America imported over $220 billion in food products last year, and 74 percent of those items are either facing higher tariffs now or will face higher tariffs starting on August 1, according to a Tax Foundation analysis published this week. The items most likely to be affected by tariffs are liquor, baked goods, coffee, fish, and beer—products that accounted for about 21 percent of total food imports last year. (However, many food products from Mexico and Canada will continue to be imported duty-free, thanks to the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, which should blunt the overall price increases on groceries.)

The exact consequences of the coming tariffs will depend on too many factors to make any predictions possible. The tariff rates themselves, and whatever price increases they trigger, are just the start. Both corporations and consumers will seek cheaper substitutes (which may often be lower quality goods) or may choose not to buy or import certain items at all. There is no price increase on a product that disappears from store shelves entirely.

Still, there's no such thing as a free lunch. Money does not fall from the sky and land in the U.S. Treasury (no, not even when the Federal Reserve is running the printer at full tilt). If tariffs weren't raising taxes (and, with them, prices), there would be nothing for Lutnick to celebrate. Next week, he might have a whole lot more to cheer—at the expense of American businesses and consumers.

Show Comments (152)