There's No Good Reason for Cities and States To Build or Subsidize Sports Stadiums

“There's no such thing as a free stadium,” says J.C. Bradbury. “You can't just pull revenue out of thin air.”

Hello and welcome to another edition of Free Agent! Don't forget to eat those July 4 leftovers, it's probably the last good day for them.

I'm away on vacation, but I've got a great interview for you to read about sports and local politics colliding over stadium subsidies. But don't sleep on the links this week, there was a ton of news about the federal government intersecting with the sports world.

Locker Room Links

- Public service announcement: In spite of one real email inquiry, Free Agent is a newsletter and does not offer private baseball lessons. But if you want to send $200 in exchange for me telling your child to choke up on the bat, you may do so.

- The GOP's "Big Beautiful Bill" is terrible for professional, and casual, gamblers.

- The bill also spends a lot of taxpayer money on the 2026 World Cup and the 2028 Olympics.

- Mexican boxer Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. was arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement days after fighting Jake Paul.

- Speaking of fights, President Trump wants to host a UFC fight at the White House with tens of thousands of attendees.

- MLS allegedly suspended three Chicago Fire fans (the soccer team, not the TV show) for a year for their "FIRE FANS CONTRA ICE" banner (the government agency, not the frozen water).

- The Supreme Court will decide if states can ban transgender athletes from women's sports teams.

- Speaking of which, elsewhere at Reason: "It was the NCAA's policy that was unfair to female competitors," writes Reason's Billy Binion. "It was unfair to [Lia] Thomas, who became a national villain for participating and a symbol of institutional rot in collegiate athletics. And it set the stage for the Trump administration to make a very, very easy layup."

- Lionel Messi, your job is safe for now:

The Stadium Scam

Sports teams and their stadiums are big businesses that are huge drivers of economic growth, and should be lured from city to city by generous subsidies and incentives that will be well worth it for governments and taxpayers, right?

Don't miss sports coverage from Jason Russell and Reason.

Wrong! Many thanks to J.C. Bradbury, a professor of economics at Kennesaw State University in Georgia, for taking the time to speak with me.

Q: My first question is a devil's advocate case for stadium subsidies. People see sporting venues go up, they sometimes see development around the stadium. They see people pouring into these stadiums however many times a year there's a home game or concert. How can you say this is not a slam dunk for economic development?

A: That's what we teach in early introductory economics classes as underpinning the difference between the seen and the unseen. We often see people spending their money in and around stadiums, and we say, "Oh, this must be net new economic activity." But what we don't see is that most of the people who are spending that money were [already] going to spend it elsewhere in the community. We don't see fewer tables being served at restaurants, fewer lanes being rented at bowling alleys, people buying things in retail outlets.

Most spending is reallocated local spending, so it's not a net new economic benefit to the community. We've been studying this for 50 years, and no one can find any increase in economic activity following the opening of a new sports venue.

Q: I think I've heard that the typical arena is getting all of its people to come at once for a big event. But if you were to spread out the total spending or total attendance over a day, or a year, the numbers aren't all that impressive.

A: A venue that I've studied very carefully, The Battery Atlanta [adjacent to the Atlanta Braves' ballpark] right near where I am in Cobb County, I've estimated that the spending that happens there is equivalent to about a Target store. That's what you're looking at. And by the way, Cobb County has seven Target stores, including one that's about a mile away from the stadium.

Q: So you're saying there's no increased spending in a metro area. One argument people might find appealing is sometimes these metro areas are near state lines, and cities or states might draw a venue into their jurisdiction. We saw this when Virginia tried to steal away the Capitals and the Wizards from Washington, D.C. I guess the argument is the new host city would suddenly get tax dollars they were not getting.

A: Going back to the stadium I was just talking about in Cobb County, Georgia, we're just over the Fulton County line where the city of Atlanta is, and that's where the Atlanta Braves used to play. Now they play in Cobb County. It's not far, distance-wise. Very similar to the distances you were talking about in Washington, D.C. So the question was, "Well, you've got all these Atlanta Braves fans coming up to Cobb County, spending their money. Shouldn't that be a net increase in spending?" And in fact, it is. I've actually done the estimates. Unfortunately though, when you measure the cost of the $300 million that Cobb is funding the stadium and the added revenue that's brought in, it's about a net loss of $15 million per year or about $50 per household in Cobb County. So there is some gain, most of it is happening during the baseball season, so it does look like maybe it is people coming for the game.

But the reality is that sports just aren't big business, particularly in the size of a metropolitan area. It's certainly not a net gain. No community can expect that it's going to get wealthy by attracting customers from across jurisdictional boundaries.

Q: To your point that sports are not big business, it's basically the entertainment industry, right? It's not essential. We would say it was weird if a city government were going to open up a chain of local movie theaters and claim the same kind of economic benefits for why they had to do this.

A: Yeah, it's sort of interesting how we've come to change the view of sports. In the early 20th century, when baseball was first establishing its foothold as the national pastime, people would've thought it was crazy that a locality would be building a stadium for the local sports team, as almost all baseball stadiums up until sort of the 1950s were privately built. And then when the stadium started to wear out, a lot of municipalities said, "Hey, we want to be seen as a major league city, we'll build you a stadium." And the owners said, "Well, wait a second, we don't have to do this anymore."

Part of it is just our attitudes have changed. I want to say it was Rob Manfred, commissioner of baseball, he [basically] said, "We really can't do professional sports without public-private partnerships," and it's just because we've become used to it. Here's how the public-private partnership works. The public partner pays and the private partner keeps all the revenue.

Q: Let's talk a little bit more about the new Commanders stadium possibly coming to downtown Washington, D.C. Even if D.C. is going to own this stadium, which I wish they wouldn't, they could still charge market rent for something like this, right?

A: There's this whole notion of ownership: Who owns the legal title to something and then who actually gets to use it? So I might legally own the car that my daughter drives, but in reality, she's the one who benefits from it and drives it all the time. In the same way that city taxpayers may own the RFK [Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium] site, the owner of the Washington Commanders likes this because then it's public property and he doesn't have to pay taxes on it. But the way these deals are written, the owner of the stadium gets to keep all the revenues and avoid all the taxes. Who cares what the legal ownership is? The de facto ownership is the team owner. And you'll often hear team owners forget this. They'll talk about, "My stadium, my revenues." I thought this was a public-private partnership.

Teams often use this. They go, "Well, this is a public venue, so it makes sense for us to subsidize it." So you talk about, "Well, could D.C. rent it out to someone else?" Well, what would make the most sense would be to knock down the stadium and build something else. And yes, that is valuable real estate that would be more valuable doing something else.

Q: What are some of the ways the costs of these stadiums get hidden from taxpayers? Instead of saying, "We're going to raise taxes on taxpayers," usually it'll be, say, "Oh, we're going to pay for this stadium deal through bonds," or, "We're going to raise taxes on hotels and rental cars," so that it's just outsiders paying for the stadium, not our own people.

A: Proponents of stadium subsidies have learned to take advantage of what economists call fiscal illusion. In the 1980s, a lot of stadiums were being funded through voter referendums, and most of these were about adding a sales tax or a property tax to build a municipal stadium and voters kept voting it down. They said, "No, we're not going to do this."

In Cleveland, a proposal got voted down, so one of the proponents of building stadiums in Cleveland did a survey and found out what would voters pay for? He said, "Oh, well, they'll be willing to pay a sin tax, that is on cigarettes and alcohol, to help fund these new stadiums." When they change the funding mechanism, they go, "Oh, we're going to tax people who are drinking and smoking and that's going to pay for the stadium, it should be free."

But the reality is that most of the people who are drinking and smoking in Cleveland are people who live in Cleveland, they're taxpayers, so you've hidden the tax. Now you might say, "Well, I don't like smoking, I don't like drinking. I feel fine taking money from these people," but that doesn't make the cost go away. It's mostly borne by locals.

So even if you argue, "I don't mind giving up that money," the opportunity cost of the money might be, "Hey, let's revitalize this other part of town. Let's build better roads. Let's reduce taxes and give it back to taxpayers to spend on other things they like."

There's no such thing as a free stadium. You can't just pull revenue out of thin air. That's why we call it fiscal illusion.

Q: What is the worst example of a stadium subsidy that you can think of, whether it was a big league stadium or a minor league one?

A: Boy, there are some real bad ones out there, it's hard to do this. The Tennessee Titans [new] stadium deal was pretty bad just because of the egregious amount of money, and they already had a new stadium right there; it's up over $2.2 billion. So, in terms of that vast amount of money and $1.26 billion is coming from the public purse split between state and local taxpayers.

The Oklahoma City Thunder's new arena is one that's particularly bad because it assigns a tax revenue stream to the team. So it's been pitched as it's going to cost $850 million for taxpayers, but it could go higher and the team gets access to the revenue stream. They can leave after 25 years and they're probably going to get well over $1 billion from this subsidy. And they're not protected from cost overrun. The mayor of the town touts this as a great public-private partnership.

Frankly, I would be embarrassed to take credit for it. I would just simply try and pretend that my predecessor had done it, we're stuck with it. But basically, they added a penny sales tax to pay for this. And they just said they didn't add it, they extended an old tax that was going to go away. And so they presented this very disingenuously to get this across the finish line. So I think the Oklahoma City Thunder arena is the worst for that reason, even though it's not the highest number.

Q: I know you're a sports fan, it's not like you hate sports. So tell us, how should this be done? How should stadium construction happen and be funded?

A: This is a private business endeavor, this is entertainment. We shouldn't be funding sports any more than we should be funding movies (although we do give a lot of public money to movies). It's perfectly fine to just let this be a private business opportunity. If you look at professional sports, I talked about it not being big in a sense relative to normal municipal economies, but look at the amount of salaries that are being paid. I mean, players are being paid hundreds of millions of dollars. Owners are paying billions of dollars for these teams. They're valuable private commodities.

If all public money were shut off today, professional sports would continue on almost as it always has, albeit people involved in it would be making slightly less money. Players would still be making salaries approaching tens of millions to hundreds of millions of dollars, and sports teams would still be worth billions [of dollars]. And the stadiums we would have would continue on and last a little bit longer. When private team owners owned their own baseball stadiums in the early 20th century, they tended to last 50, 60 years because, "Hey, I don't get a free stadium. It's still worthwhile, why don't I keep playing in it?" So that's sort of my case, is that this should be a private endeavor and we need to return it back to the private market because it absolutely makes no sense whatsoever for governments to be involved in this at all. It's simply indefensible.

Q: There are examples of privately financed modern stadiums like SoFi Stadium, and I think Gillette Stadium is widely regarded as a high-class stadium too, right?

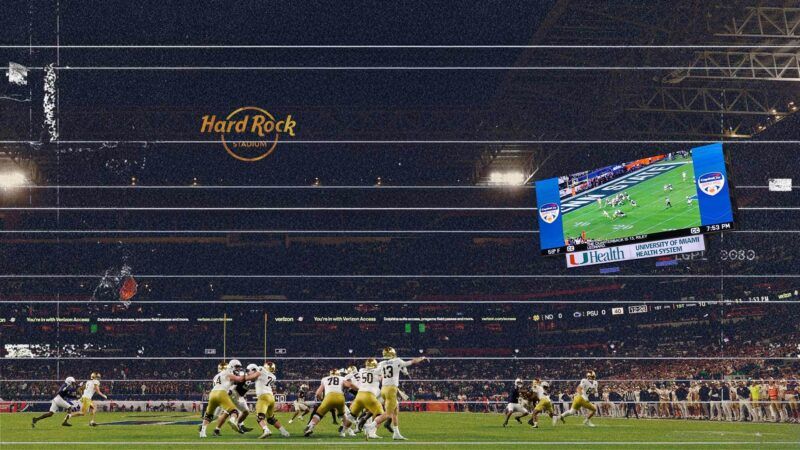

A: Both of those, and if you want to look at a great example, there's Hard Rock Stadium in Miami, which was built by Joe Robbie, the former owner of the Miami Dolphins. And he basically got tired of dealing with government, said, "I'm just going to build my own stadium." And really, the funding model should have changed right then. We should have gone back and said, "It's totally possible." But the reason why I single out Hard Rock Stadium is because it was built in the 1980s and it was recently refurbished. It's hosted Super Bowls, it's hosted World Series, it hosts college football national championships. There's no need for government to be involved here, there is no market failure. The Carolina Panthers' stadium, smaller market. It was a private stadium (although it recently got $650 million in subsidies for renovating).

It's absolutely unconscionable for us to do this, particularly when we think about the people who own this tend to be some of the wealthiest people in all of human history. This makes absolutely no sense.

This interview has been condensed and edited for style and clarity.

Replay of the Week

Hope your Fourth of July weekend was as much fun as this.

That's all for now. Enjoy watching the real game of the weekend, Australia against the West Indies in cricket.

Show Comments (33)