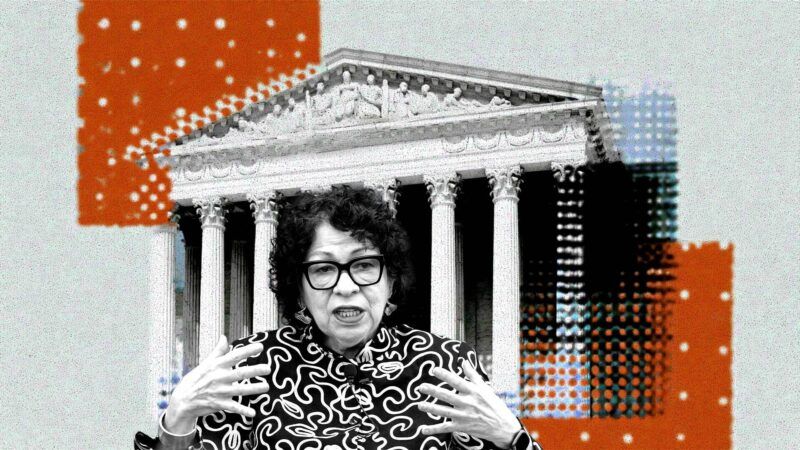

Sotomayor Is Right. Trump's 'Third Country Removals' Raise Serious Due Process Worries.

The liberal justice faults the majority for leaving deportees to “suffer violence in far-flung locales.”

The U.S. Supreme Court this week allowed the Trump administration to resume deporting noncitizens to countries with which they have no ties.

Why did the Supreme Court do it? Unfortunately, we don't know why because the Court declined to say. The ruling came in the form of an unsigned emergency order that offered zero explanation. But Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, did file a dissent. And that dissent painted an extremely unflattering picture of what the other six justices were up to.

You’re reading Injustice System from Damon Root and Reason. Get more of Damon’s commentary on constitutional law and American history.

The case is known as Department of Homeland Security v. D.V.D. It arose when the Trump administration sought to deport a group of men—all immigrants who have been convicted of crimes—to South Sudan and other nations where the immigrants have no connections, a process known as "third country removal."

Third-country removals are legal, but only as a kind of last resort. When it is "impractical, inadvisable, or impossible" to deport an alien to "the country of which the alien is a citizen, subject, or national," or to "the country in which the alien was born," or to "the country in which the alien has a residence," it is only then permissible under federal law to deport the alien to "a country with a government that will accept the alien."

Third-party removals must also conform to the Foreign Affairs Reform and Restructuring Act, which says that it "shall be the policy of the United States not to expel, extradite, or otherwise effect the involuntary return of any person to a country in which there are substantial grounds for believing the person would be in danger of being subjected to torture."

A federal district judge blocked the third-country removals at issue in this case because the Trump administration failed to provide the men with a "meaningful opportunity" to object to being deported to places where they might be tortured, such as war-torn South Sudan. ("Do not travel to South Sudan due to crime, kidnapping, and armed conflict," the State Department currently advises.) In other words, the judge ruled against the Trump administration because the men were being denied due process, which the Constitution provides to persons, not just to citizens.

The Supreme Court's emergency order lifted that block, thereby allowing the deportations to proceed.

Here is how Sotomayor's dissent characterized the underlying legal dispute: "Plaintiffs merely seek access to notice and process, so that, in the event the Executive makes a determination in their case, they learn about it in time to seek an immigration judge's review." The Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment, she maintained, "unambiguously guarantees that right."

Does the majority disagree that such due process is "unambiguously" guaranteed in a case like this? Do the other six justices believe that due process was actually satisfied by the Trump administration's actions? It would be nice to know what the Court was thinking on such a pressing legal matter.

"Apparently," Sotomayor wrote, "the Court finds the idea that thousands will suffer violence in far-flung locales more palatable than the remote possibility that a District Court exceeded its remedial powers when it ordered the Government to provide notice and process to which the plaintiffs are constitutionally and statutorily entitled."

I share Sotomayor's concerns. The Trump administration has not exactly earned the benefit of the doubt when it comes to its adherence to the letter of the law on immigration (or on birthright citizenship, or on tariffs, or on war powers). So if the Supreme Court is going to give the green light to Trump in a case like this one, the Court should, at the very least, share its rationale so that we can fully assess its seemingly suspect judgment for ourselves.

Show Comments (100)