Trump's Unconstitutional Act of War

Plus: A criminal justice case that managed to unite Alito and Gorsuch.

When President Barack Obama unilaterally ordered the bombing of Libya in 2011, I argued that Obama was acting "in violation of the U.S. Constitution and the War Powers Act until he gets Congress's approval." The exact same argument now applies to President Donald Trump's unilateral bombing attack on Iran.

Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution places the power "to declare War" exclusively in the hands of Congress. The president of the United States, whose own limited powers are separately enumerated in Article II, possesses no lawful authority to launch a war on his own.

Historical evidence from the framing era of the original Constitution supports the point. In a 1798 letter to Thomas Jefferson, for example, James Madison observed that "the constitution supposes, what the History of all [Governments] demonstrates, that the [executive] is the branch of power most interested in war, & most prone to it. It has accordingly with studied care, vested the question of war in the [Legislature]."

You’re reading Injustice System from Damon Root and Reason. Get more of Damon’s commentary on constitutional law and American history.

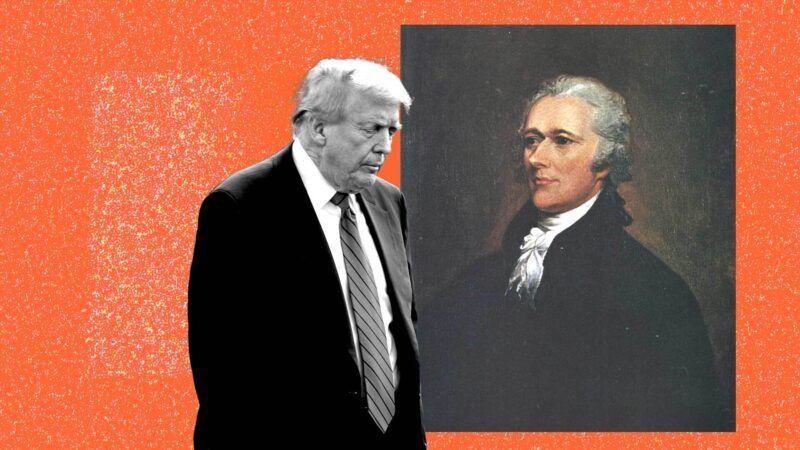

Likewise, in 1793, Alexander Hamilton wrote that "the Legislature can alone declare war, can alone actually transfer the nation from a state of Peace to a state of War." Furthermore, Hamilton wrote, "if the Legislature have a right to make war on the one hand—it is on the other the duty of the Executive to preserve Peace til war is declared."

Madison and Hamilton did not always see eye to eye on matters of presidential power. Madison preferred a more restrained executive branch while Hamilton preferred a more unbounded one. So it is notable that the two were in relative harmony about the president's lack of any lawful power to launch a war.

The work of St. George Tucker provides additional framing-era support for this position. Tucker, a veteran of the Revolutionary War and professor of law at the College of William and Mary, published the first extended commentary and analysis of the new Constitution. His 1803 View of the Constitution of the United States was basically the original con-law textbook.

"In England the right of making war is in the King," Tucker observed. "With us the representatives of the people have the right to decide this important question." And "happy it is for the people of America that is so vested," he declared. In a monarchy, Tucker wrote, "the personal claims of the sovereign are confounded with the interests of the nation over which he presides, and his private grievances or complaints are transferred to the people; who are thus made the victims of a quarrel in which they have no part, until they become principals in it, by their sufferings."

To be sure, there were some members of the founding generation who did argue that the president should possess an independent war-making authority. But their voices were effectively drowned out in a sea of disapproval.

During the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, for instance, Pierce Butler of South Carolina stated that he "was for vesting the power in the President, who will have all the requisite qualities, and will not make war but when the Nation will support it."

Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts promptly spoke up in opposition to Butler, declaring that he "never expected to hear in a republic a motion to empower the Executive alone to declare war."

George Mason of Virginia agreed with Gerry, declaring that he too was against "giving the power of war to the Executive." Why? Because the executive was "not safely to be trusted with it."

In the end, Butler's view went nowhere. The framers of the Constitution wisely placed the power to declare war in the hands of Congress, which is where that power still properly belongs today.

In Other Legal News

The U.S. Supreme Court decided an important criminal justice case last week by a vote of 7–2, which is not an unusual numerical sorting these days. What made the vote unusual was the fact that the two dissenters were Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch, who often butt heads in divided criminal justice cases. So, what happened here?

Last week's decision in Esteras v. United States centered on the discretion of federal judges to revoke a defendant's supervised release from prison. Federal law says that a judge may only revoke supervised release "after considering" a list of sentencing factors "set forth" in the federal sentencing law.

"Conspicuously missing from this list," stated the majority opinion of Justice Amy Coney Barrett, was a different provision set forth elsewhere in the law, "which directs a district court to consider 'the seriousness of the offense, to promote respect for the law, and to provide just punishment for the offense.'" Moreover, according to Barrett's opinion, "Congress's decision to enumerate most of the sentencing factors," while leaving others out of that enumeration, "raises a strong inference that courts may not consider that [other] factor when deciding whether to revoke a term of supervised release."

Writing in dissent, Alito, joined by Gorsuch, complained that "the Court interprets the Sentencing Reform Act to mean that a federal district-court judge, when considering whether to impose or alter a term of supervised release, must engage in mind-bending exercises." For instance, Alito wrote, "the judge must consider what is needed to 'dete[r]' violations of the law or to rehabilitate a defendant, i.e., to cause him to lead a law-abiding life, but cannot be influenced by a desire 'to promote respect for the law.'"

In short, the Supreme Court held that district judges must stick to the enumerated sentencing factors and not consider any other factors when revoking a defendant's supervised release. Alito and Gorsuch would have ruled otherwise and allowed the judges to take such other factors into consideration.

This outcome will surely be welcomed by criminal justice reform advocates, as it requires judges to stick to the letter of the law and not venture beyond it when ordering someone back to prison. As for Gorsuch, the case is another reminder that despite his seemingly libertarian legal instincts in certain areas, he is not the thoroughgoing libertarian that some of us would like to someday see on the bench.

Show Comments (86)