America Is Losing Trump's Trade War to Itself

If tariffs are so great, why has Trump shown a willingness to back down from his threats if other countries agree to certain conditions?

The first few weeks of the second Trump administration were a whirlwind of counterproductive, illogical trade policies.

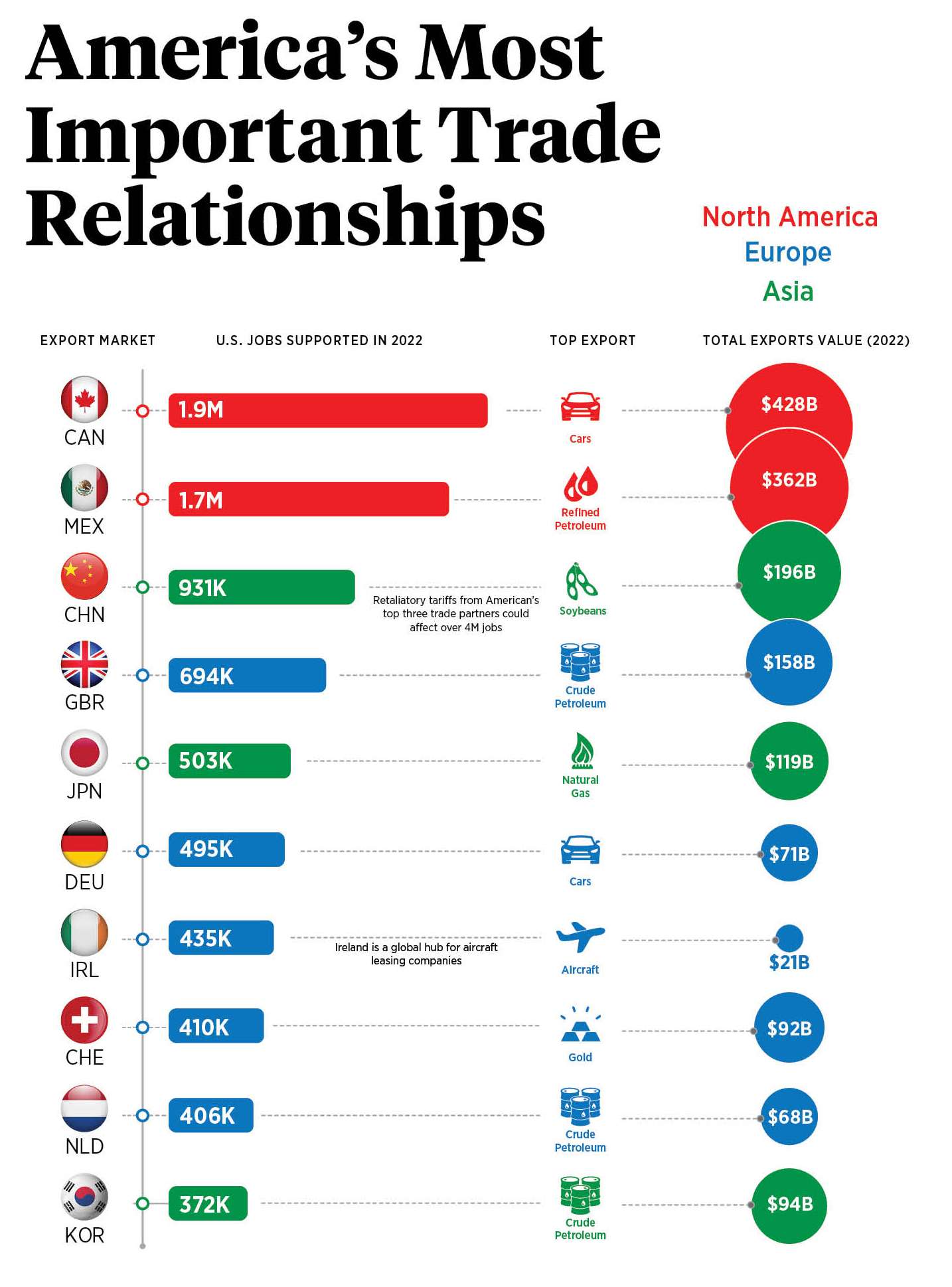

Trump returned to the White House with a promise to raise tariffs on his first day in office. That morphed into a threat to tax all imports from Mexico and Canada (two nations with which Trump negotiated a new trade deal during his first term) on February 1. When that date arrived, Trump backed down. Meanwhile, he slapped a new 10 percent tariff on all goods imported from China and followed that with a 25 percent tariff on all steel and aluminum imports. On March 3, the president reversed course again and moved forward with blanket tariffs on imports from Mexico and Canada. Trump also began the process of implementing what he calls "reciprocal tariffs" on all imports, with specific rates to be determined later this year.

That was just the first six weeks. By the time you read this, a global trade war could be in full swing—or Trump may have extracted whatever vague concessions he's seeking with this chaotic attack on the peaceful exchange of goods.

During his first tenure in office, the president (and some of his top advisers, including Peter Navarro, who now heads the White House's trade policy team) was obstinate in his claim that China was paying the cost of his tariffs. That was, of course, false. Study after study confirmed what economists had already explained: Tariffs were paid by the American businesses and consumers that purchased tariffed products. The promised benefits for American manufacturers never really materialized, and the small number of jobs created by imposing tariffs on imports were costly—one 2018 study from the Peterson Institute for International Economics concluded that Trump's 2018 steel tariffs cost $650,000 per job created.

Much of the chaos Trump has unleashed speaks to a bigger problem: Trump's theory of how to use tariffs is deeply illogical, even once you get past the economic illiteracy. It is worthwhile to think through those arguments, if only because they are likely to resurface as justifications for tariffs in other contexts over the coming years.

Trump loves to claim that tariffs will make America a wealthier nation. "The tariffs are going to make us very rich and very strong," Trump said in late January, just before launching (and then pausing) his North American trade war. "They don't cause inflation. They cause success." He's used variations of this line for years, and on the campaign trail in 2024 he would often claim that America was at its peak during the 1890s, when tariffs were significantly higher than they are today.

That's nonsense. Americans are far wealthier today than in the 1890s, when most people did not have access to indoor plumbing, electricity, or modern medical care, and when the average hourly wage was less than 14 cents—that's less than $5 today when adjusted for inflation.

But even if you accept Trump's premise that tariffs are the key to making America wealthy again, his behavior is illogical. He spent the first few weeks of his new term threatening to place those wealth-generating, Golden Age–restoring tariffs on Canada and Mexico and then backed down when both countries agreed to make some minor changes to how they police their borders. Then, he went ahead with the higher tariffs anyway.

That should make us wonder: If tariffs are the key to tremendous wealth, shouldn't Trump implement them no matter what the leaders of any other countries do or say? If we really can tax our way to prosperity, as Trump claims, why wouldn't we do that? Perhaps it is because we can't, and those claims are lies.

The other arguments Trump and his allies have deployed are just as illogical.

Take the claim that tariffs were a negotiating tool to force Canada and Mexico to crack down on the flow of fentanyl into the United States. In the executive order authorizing tariffs on goods from Mexico and Canada, Trump wrote that "the sustained influx of illicit opioids and other drugs has profound consequences" for the country and "threatens the fabric of our society."

A literal reading of the executive order suggests that Canadian imports like maple syrup and timber are somehow to blame for the opioid crisis. That makes no sense.

If the diagnosis is foolish, then the treatment is even sillier. Is there any other context in which higher taxes on legal goods would reduce the smuggling of illegal ones? Raising taxes on beer won't stop people from using cocaine.

Equally misguided is Trump's idea about using tariffs to reduce America's trade deficit with other countries. To understand why, think about the transactions that occur between your household and your favorite grocery store. You buy lots of goods from the grocery store, but it never purchases anything from you—therefore, you're running a sizable trade deficit.

Tariffs are nothing more than a tax on those transactions. Trump's logic says that you could be wealthy if you mailed $25 to the U.S. Treasury for every $100 in groceries that you purchase. That's ridiculous. You'd be poorer, and the trade deficit with the store would still exist. Perhaps you'd choose to spend less on groceries to avoid the extra cost imposed upon yourself, but that should only illustrate how the extra $25 reduced your standard of living.

Finally, Trump has also promised that tariff revenue can be used to eliminate the income tax. Tariffs do indeed generate some revenue for the government, though you'd have to set tariff rates exorbitantly high to offset the $2.2 trillion in individual income taxes paid every year.

Maybe that tradeoff is worth it, but there's a bigger logical hole in this idea: In order for a tariff to work as a revenue-generating policy, it must actually exist—because a threatened tariff generates no revenue. For the same reason, a tariff that exists only to persuade another country to take some specified action is useless for revenue, because it would be removed once the other country complies.

Tariffs cannot be both the primary means of funding the federal government's budget and a tool of foreign policy. In fact, they're not particularly effective at either of those jobs.

Unfortunately, Trump seemingly lacks any awareness about the economic costs of his tariff obsession, and he does not have a strong sense of intellectual consistency. At this rate, American businesses and consumers should prepare for four years of uncertainty, higher costs, and logical contradictions.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Trade War We're Losing to Ourselves."

Show Comments (92)