The Cold War Broadcasting Apparatus Should Shut Down

Dissidents resisting authoritarian regimes should be independent of the United States—and so should their media sources.

The U.S. Agency for Global Media—the bureaucracy that runs the Voice of America, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, and Radio y Televisión Martí, among other operations—might be about to die. On Friday, President Donald Trump issued an order to shut it down "to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law." In a follow-up statement Saturday, the White House derided the Voice of America as "radical propaganda" and listed several stories on the network that the administration found objectionable.

Trump has been complaining about the Voice of America since his first term, and last month Envoy for Special Missions Richard Grenell declared it and Radio Free Europe a "relic of the past." But most of the administration's criticism has been focused on these outlets' content, not their existence, and by some reports the agency has reacted by cracking down on material critical of the president. So it was fair to fear that we were watching a version of the playbook the GOP keeps using on domestic public broadcasters: You threaten to defund them, and then they protect themselves by firing some figures who conservatives don't like and/or hiring some that they do. Maybe the Voice of America isn't really on the chopping block, you might have thought. Maybe it's just getting a MAGA makeover.

Friday's move is the strongest sign yet that what's happening at this agency is not merely a purge of programming the president dislikes. More than three decades after the end of the Cold War, we might finally be shutting down the Cold War broadcasting apparatus.

If so, it's about time. And you don't have to agree with the White House's complaints about the Voice of America or the journalists who work there to think that's true. Indeed, if you're a liberal who doesn't want to see that institution turned into a federally funded Newsmax for Foreigners, you should be relieved if it turns out that at least we won't get that.

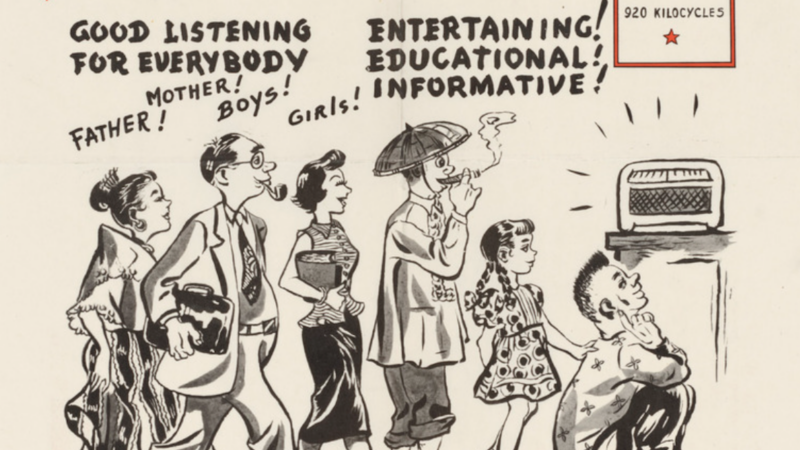

The agency's defenders argue that oppressed people in other countries rely on these outlets to hear news and opinions that haven't been vetted by the local authorities. Whatever truth there may have been to that when, say, a Romanian family would tune to Radio Free Europe after hours for an alternative to the Communist dictatorship's propaganda, it is far less convincing at a time when there are countless ways to get information across borders (and countless exile groups willing to pay for such projects themselves).

What's more, such efforts are much more persuasive when they aren't subsidized by the state. In 2002 I interviewed Zia Atabay, an Iranian-American pop singer who had founded National Iranian Television—a satellite TV operation based in a former North Hollywood porn studio that transmitted cultural and political programs to Iranian exiles around the world and to illicit dishes in his homeland. He wasn't necessarily averse to getting federal money (and by one report may have received some in later years), but he also understood the problems such sponsorship would bring. "The American government wants to open another station," he told me. "My experience is that when a government opens a station, nobody trusts it."

In his 2005 book Tehran Rising, the neoconservative analyst Ilan Berman declared that "the broadcasting efforts of Iranian expatriate elements have proven to be more effective than anything the United States has brought to bear." He saw this as an argument for pouring public money into the expatriates' efforts, but to me it looked like an argument that they were capable of working without Washington's support. Groups resisting authoritarian regimes should be independent of the United States—and so should their media sources. That might not be palatable to people who want not just to give dissenters a boost but to steer them in the directions D.C. prefers. But if you want actual freedom in these countries, not just pliant allies, you should want the protesters and their press to be independent, indigenous forces.

A year after Berman's book appeared, the Bush administration launched the Iran Democracy Fund, in part to subsidize broadcasts to the Islamic Republic. When the Obama administration gutted the fund a few years later, some opponents of the Iranian regime complained, but others celebrated. "The U.S. democracy fund was severely counterproductive," dissident Akbar Ganji told the BBC, explaining that "we were all accused by Iran's government of being American spies because a few groups in America used these funds." And yes, most of that money was steered to broadcast studios via the bureaucracy now known as the Agency for Global Media.

I should acknowledge that the above criticisms do not, for the most part, apply to the agency's internet freedom efforts. Notably, the Open Technology Fund (OTF), launched in 2012 to help people evade barriers to receiving Radio Free Asia, has helped develop several technologies to circumvent online censorship and surveillance. Since it circulates tools that anyone can use, this does allow people to operate independently—including people trying to avoid the censorship and surveillance being underwritten by the same U.S. government that created the OTF. The fund also insists that these tools be open source, giving wary users a chance to check whether the software contains spyware or is otherwise insecure.

But the very fact that the OTF is funded by the feds puts it at risk of political interference. When Michael Pack took over the Agency for Global Media five years ago, he made an unsuccessful effort to redirect OTF money to proprietary software that doesn't reveal its source code—and to fire the fund's board when it objected. Happily, the OTF has outgrown its origins in Radio Free Asia and is now formally an independent nonprofit, and in 2023 it launched a Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) Sustainability Fund, with financial backing from the private sector, to "support the long-term maintenance of FOSS projects and the communities that sustain them." Unhappily, the OTF still gets the bulk of its grants from the agency that birthed it. It would be better off on its own.

The Agency for Global Media isn't dead yet. Because it was chartered by Congress, the institution itself can't be axed without congressional authority; Congress has also allocated funds for specific purposes there. Trump's executive order appears to recognize that: It gives the agency's chief a week to submit a report "explaining which components or functions of the governmental entity, if any, are statutorily required and to what extent." This could, of course, set us up for a legal battle over how closely that report reflects those statutes. One way to avoid such a slog would be for Congress to step up and pull the U.S. government out of the international broadcasting business.

If it does, Congress should ensure as it shutters these networks that it preserves their archives. Partly in the interest of historical transparency, and partly because, as even a longtime foe of government-run broadcasting like me will concede, there was a lot of good stuff on shows like Music USA. Send the old tapes to the Internet Archive and keep that history alive.

But the outlets that transmitted that music are zombies from Cold War. They should have stopped their shuffling long ago.

Show Comments (30)