Passport Applicants May Have To Affirm That They Are 'Not Required To Register' As Sex Offenders

The proposed State Department policy would add to the irrational burdens that registrants face.

Under a proposed State Department policy, U.S. passport applicants would have to affirm that they are "not required to register" as sex offenders. If they are "required to register," they would have to submit a "supplementary explanatory statement under oath."

The State Department says that change, which it announced in a Federal Register notice seeking public comment last month, is "in accordance with" the International Megan's Law (IML), which requires "unique passport identifiers" for "covered sex offenders." Although that 2016 law is ostensibly aimed at preventing "child sex tourism," it applies to many people who have never engaged in such conduct or shown any propensity to do so. The proposed passport affirmation sweeps even more broadly, and it is apt to have a chilling effect on international travel by Americans who are required to register as sex offenders—a category that includes nearly 800,000 people, many of whom have never committed crimes anything like those targeted by the IML.

The State Department notice, which also describes revisions to comply with President Donald Trump's executive order regarding "sex" vs. "gender identity," says the registration query would be included in the "Acts or Conditions" section of the passport application. The current version of that affirmation says: "I have not been convicted of a federal or state drug offense or convicted of a 'sex tourism' crimes statute, and I am not the subject of an outstanding federal, state, or local warrant of arrest for a felony; a criminal court order forbidding my departure from the United States; or a subpoena received from the United States in a matter involving federal prosecution for, or grand jury investigation of, a felony."

The revision would add a clause saying the applicant "is not required to register as a sex offender." That presents a couple of puzzles.

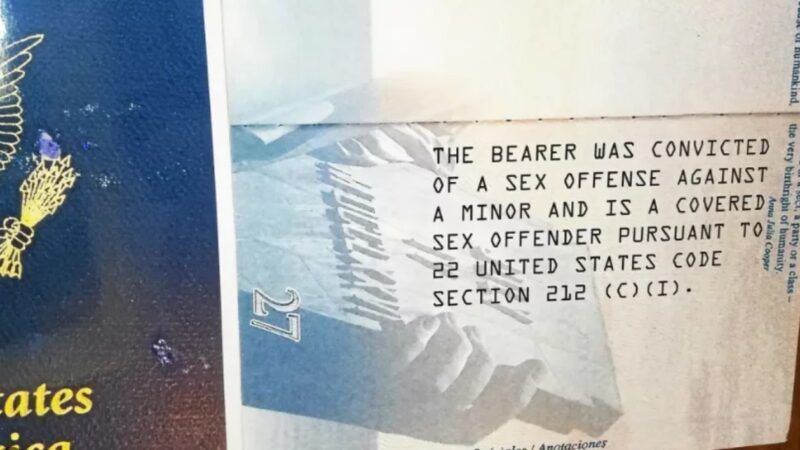

Judging from the State Department's invocation of the IML, this change is meant to facilitate "unique passport identifiers" for sex offenders covered by that law. The unique identifier, which the State Department began requiring in 2017, consists of a passport notation that says, "The bearer was convicted of a sex offense against a minor, and is a covered sex offender pursuant to 22 United States Code Section 212b(c)(1)."

Contrary to the implication of that language, sex offenders covered by the IML are not limited to adults convicted of sexually assaulting minors. They include people convicted of misdemeanors as well as felonies, people who committed their offenses as minors, people who as teenagers had consensual sex with other teenagers, and people who committed noncontact offenses such as sexting, streaking, public urination, and looking at child pornography. And contrary to the IML's avowed goal, they include people who were convicted decades ago and have never reoffended.

Does that policy make any sense? In 2016, when a federal judge dismissed a constitutional challenge to the IML, she said the law easily passed the "rational basis" test. "Under rational basis review," she explained, "a law 'may be overinclusive, underinclusive, illogical, and unscientific and yet pass constitutional muster.'"

The proposed State Department requirement extends even further than the IML. It covers all registrants, regardless of whether their offenses involved physical contact or had anything to do with children. It is not clear why the State Department decided to cast such a wide net if its aim is to identify passport applicants covered by the IML.

Nor is it clear what "required to register" means. That phrase, a passport applicant might reasonably surmise, refers to the law of the state where he lives. But it also could be interpreted as encompassing federal law, which imposes an independent registration requirement based on criteria that may be different.

"Unless a jurisdiction's laws require an offender to register, a jurisdiction generally will not register the offender," the Justice Department notes. "As a result, it is possible that an offender will be required to register under SORNA [the federal Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act] but, because the jurisdiction's laws do not require registration for the offense of conviction, the jurisdiction where the offender lives, works, or attends school will refuse to register the offender." What happens then?

The Justice Department during the Biden administration insisted that sex offenders are subject to SORNA's requirement and the associated criminal penalties even if it is not possible for them to register in the state where they live. That position, a federal judge ruled in 2023, violated the constitutional right to due process. But whether or not someone can be convicted under SORNA for failing to do the impossible, the potential inconsistency between state and federal law poses a conundrum for passport applicants: Are they "required to register" because of SORNA even though they are not "required to register" in their state of residence?

The answer to that question could be legally consequential, since lying on a passport application is a federal felony punishable by up to 10 years in prison. And even when an applicant errs on the side of caution by declining to affirm that he is "not required to register," he still has to submit a "supplementary explanatory statement" that clarifies whether he is covered by the IML, which also could expose him to criminal liability if he gets anything wrong.

This whole process is intimidating, perhaps deliberately so. In fact, given that the affirmation about an applicant's registration status would be subsumed under "Acts or Conditions," registrants might erroneously conclude that they are not allowed to obtain passports at all. The requirement would add to the frequently unjust, irrational, and unconstitutional burdens that registrants already face, including residence, employment, and travel restrictions that extend and magnify their punishment without any countervailing public safety benefit.

The State Department did not respond to a request for comment prior to publication.

CORRECTION: This post has been revised to clarify that the new policy has not been finalized yet.

Update, March 17: I received a response from the State Department that does not really clarify the breadth of the proposed affirmation: "We have not changed our policy. The proposed changes to the passport application forms are to more clearly indicate to covered sex offenders that they need to self-identify."

Show Comments (20)