Affirmative Consent Is Back

And it's still a bad legal standard.

In the later years of the second Obama administration, affirmative consent was all the rage. Affirmative consent refers to the idea that "no means no" doesn't cut it; when it comes to sex—or even kissing—all actions must be explicitly and affirmatively agreed upon.

There's nothing wrong with affirmative consent as an ideal, though some may argue it's the antithesis of erotic. But affirmative consent as a legal standard is unworkable and dangerous. And as a feminist standard, I think it leaves a lot to be desired too.

Alas, affirmative consent back, in the form of a very anachronistic bill in Utah.

You are reading Sex & Tech, from Elizabeth Nolan Brown. Get more of Elizabeth's sex, tech, bodily autonomy, law, and online culture coverage.

Redefining Consent in Utah

Utah House Bill 377, from state Rep. Angela Romero (D–Salt Lake City), would amend the state's law on rape and sexual assault to say that "silence, lack of protest, or lack of resistance alone do not demonstrate consent."

"Romero has filed several bills in recent years that would create a new third-degree felony offense for instances in which a perpetrator fails to get consent from a victim through words or actions," reports KSL-TV. "But those bills have been met with resistance or ignored all together."

Her latest effort is described as a "scaled-back proposal." But, clearly, this is the same concept as the others, just packaged differently.

Say two people are cuddling, kissing, or engaged in more explicit sexual activity. When one party starts to go further—be that by initiating intercourse or simply touching someone's breasts or "anus, buttocks, pubic area, or any part of the genitals" or "otherwise tak[ing] indecent liberties"—the other party does not object, leaving the initiator to believe this escalation is desired.

Under Romero's proposal, the first party could be guilty of rape or sexual abuse.

Granted, this would not automatically be the case. Here's the full consent clause that would be added to the state's sex crimes statute: "While silence, lack of protest, or lack of resistance are among circumstances that may be considered in determining whether consent was given, silence, lack of protest, or lack of resistance alone do not demonstrate consent."

But in a way, that makes things more muddy. If someone doesn't say "stop" or "no," it might be fine or it might be rape?

The only way to be sure you weren't violating the law would be to obtain affirmative consent at every step of an intimate encounter—before kissing, then again before any sexual touching, and so on.

An Unworkable Standard

There are obviously some situations in which affirmative consent is a good idea. If two people are hooking up for the first time, explicitly asking before initiating sexual intercourse is a no-brainer. Perhaps, too, when moving from mild sexual activity to more intimate acts.

But affirmative consent as a legal standard doesn't merely apply in situations like those. It says that explicit asking and agreeing is necessary between any two people, even those who have been intimate together many times before. And it says this agreement is needed at every point in an intimate encounter, even when moving from something like kissing to what our grandparents might have called "light petting."

This means even members of a long-term relationship can claim sexual assault if a partner failed to get an enthusiastic yes before proceeding from foreplay to sex, or kissing to foreplay. That may be unlikely to happen in most cases, but the point is it could happen. If one partner angered the other enough, or attempted to end the relationship, the aggrieved partner could report the other for rape and not be wrong. That's less than ideal.

Besides, technically making "rapists" out of every partnered person who engages in normal sexual conduct seems like it could backfire from a social norms perspective, perhaps leading many people to take sexual assault claims less seriously.

Now, if the tradeoff was that prosecuting serious sexual assaults and rapes became much easier, that might tip the scales toward affirmative consent a little. But the main problem with prosecuting rape and sexual assault is that it very often comes down to nothing more than the word of one person against the other—"I said stop" vs. "No, they didn't."

Switching the standard from no means no to yes means yes does nothing to overcome this prosecution problem. It's just as easy for a rapist to lie about someone saying "yes" as it is to lie about them not saying "no." Motivated rapists are unlikely to be the least deterred by a switch in standards, nor more easily prosecuted.

A Dangerous Norm for Young Women

One of the most dangerous aspects of affirmative consent has to do with the messages it sends to (young) women.

Obviously, women can be sexual aggressors and men can be victims of assault. And, obviously, sex involving same-sex partners or nonbinary people exists. But more often than not, when we're talking about rape and sexual assault, it's a gendered crime, with women as the victims and males as the perpetrators. And, indeed, most discussion about affirmative consent is framed this way too.

What affirmative consent effectively says is that women are too fragile or feeble to be able to express their sexual wishes, even with something as simple as saying "stop" or "no" to a sexual advance they're not into.

The underlying premise here seems very antifeminist to me. (Also confusing: If women are too delicate to express displeasure when presented with an unwanted advance, how are they suddenly confident enough to say "no" when explicitly asked if it's OK?)

What's more, it puts young women at risk. It teaches them they shouldn't have to speak up about their sexual desires or accept any agency in intimate encounters. That the onus is on men to seek their permission and, if they don't, it's regressive to expect women to respond proactively.

Not only is this a philosophically offensive premise, it seems destined to lead to more problems—more women feeling violated, and more women being raped.

We do not live in a world where affirmative consent is the norm, and, even as it's popularized, many people are going to continue to abide by the idea that a lack of rejection is consent. People can bemoan that all they like—and maybe they should—but it's true, and accepting reality is an important step in helping people cope with real-world situations.

If young women are going into sexual encounters being told that it's scary to say no, or somehow not their responsibility, they are disempowered. They're less likely to say "no" or "stop" when it matters and to physically leave situations where their word isn't being heeded. This could leave people who actually are ambivalent about sexual activity as it happens vulnerable to reframing it, or having others reframe it, as exploitation. Worse—much worse—it could lead to women avoiding taking simple steps to stop themselves from being sexually assaulted.

Certainly, many assailants will be impervious to someone saying no. But there are also, clearly, situations in which a person might mistake a lack of rejection for consent, and simply verbalizing that rejection—saying "stop" or "no" or whatever—would lead them to stop.

Would it be better if everyone stopped and got explicit consent when there was any ambiguity? Sure! But absent this very unlikely development, it's better to teach women to clearly express themselves with sexual partners than to let them get raped because of misunderstandings and then be able to prosecute their partners afterward.

South Carolina Bill Would Ban Speech About Abortion

South Carolina Senate Bill 323 would end abortion-ban exceptions for cases of rape, incest, and fatal fetal anomaly and require a video called "Meet Baby Olivia," developed by the pro-life group Live Action, to be shown in public schools. It would also make it a felony to even talk about abortion in some circumstances.

"Pro-choice websites would be illegal, as would hosting or maintaining a website that tells women how to get abortions. Advertising abortion medication, whether for sale or for free, would also be illegal," Abortion, Every Day blogger Jessica Valenti writes.

Valenti is referring to a portion of the bill that defines "aiding and abetting" abortion to include "providing information to a pregnant woman, or someone seeking information on behalf of a pregnant woman, by telephone, internet, or any other mode of communication regarding self-administered abortions or the means to obtain an abortion, knowing that the information will be used, or is reasonably likely to be used, for an abortion." Aiding and abetting abortion would also include "providing a referral to an abortion provider" or "hosting or maintaining an internet website, providing access to an internet website, or providing an internet service purposefully directed to a pregnant woman who is a resident of this State that provides information on how to obtain an abortion, knowing that the information will be used, or is reasonably likely to be used for an abortion."

Violating these rules could result in a prison sentence of up to 30 years.

More Sex & Tech News

• BuzzFeed founder and CEO Jonah Peretti is helping to launch a new social media platform "built specifically to spread joy and enable playful creative expression"—and has penned a quite long and pretentious preamble to his announcement.

• On life, liberty, and the right to shitpost

• The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) is fighting against a Washington bill that would require disclosure notices on AI-generated content. The "government can no more compel an artist to disclose whether they created a painting from a human model as opposed to a mannequin than it can compel someone to disclose that they used artificial intelligence tools in creating an expressive work," FIRE Legislative Counsel John Coleman said. "Developers and users can choose to disclose their use of AI voluntarily, but government-compelled speech, whether that speech is an opinion or fact or even just metadata…undermines everyone's fundamental autonomy to control their own expression."

• "A New York doctor has been indicted in Louisiana on felony charges for allegedly providing an abortion across state lines via mail," Reason's Autumn Billings reports. "This is the first case in which a doctor has been criminally charged for sending abortion-inducing drugs across state lines since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022."

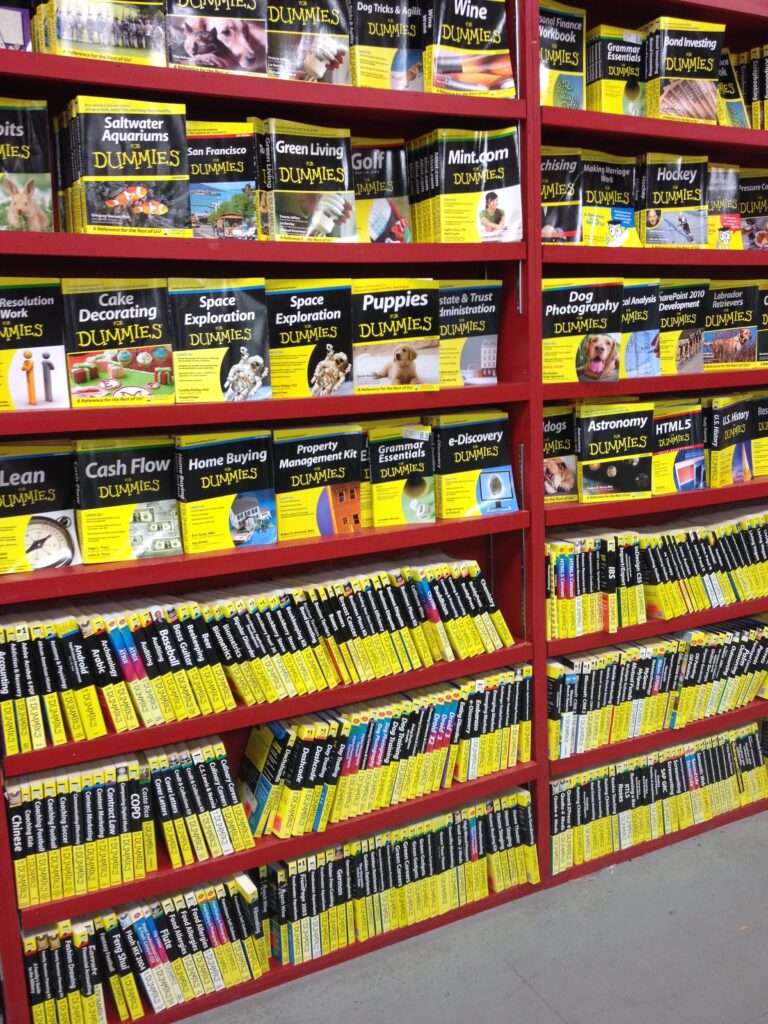

Today's Image

Show Comments (33)