A Taxpocalypse of Rising Rates Is Coming For Americans if Congress Doesn't Act

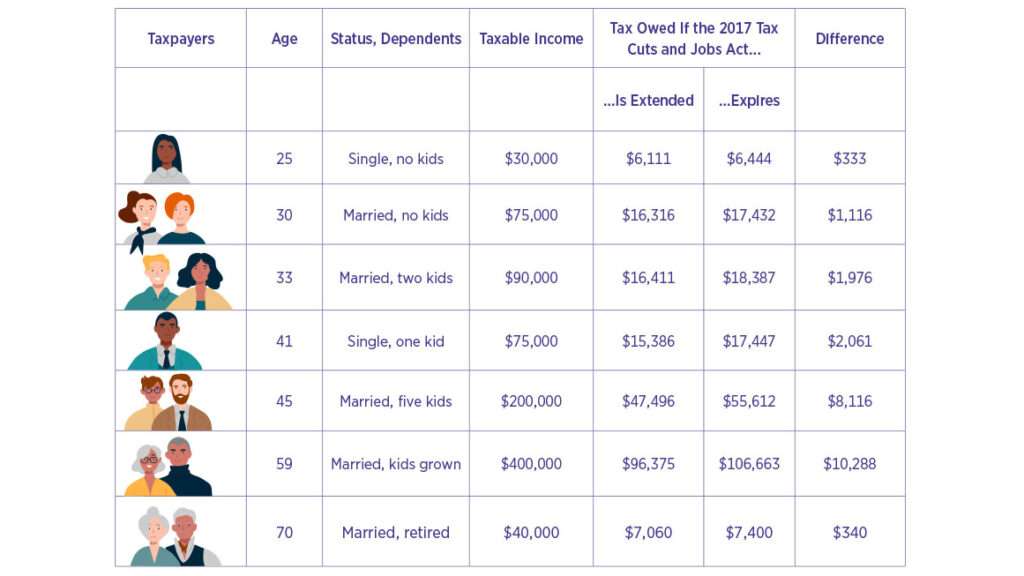

Here's how expiring tax cuts could affect you.

When the new session of Congress opens on January 3, the clock will already be ticking toward the most important set of fiscal decisions lawmakers will make this decade.

Decisions made through the end of 2025 will determine the fate of literally trillions of Americans' dollars. Will they remain in wallets, bank accounts, and retirement portfolios, or will they flow to the U.S. Treasury to fund wars and welfare?

This "fiscal cliff" is eight years in the making. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) revamped both the federal corporate and individual income tax codes. But while the new, lower, corporate income tax rate (and associated changes) were made permanent, many changes to the individual tax code were temporary. That includes the higher standard deduction, expanded child tax credit, and the lower tax rates that have allowed nearly all taxpayers to keep more of their own money these past several years.

Unless those provisions are extended or made permanent by the end of 2025, the higher pre-TCJA policies will automatically return. That would mean higher taxes for nearly all taxpaying Americans.

Of these complex and interconnected issues, those individual income tax rates are the most pressing for Congress to solve. Under the TCJA, the top marginal rate was reduced from 39.6 percent to 37 percent—with rates for other tax brackets falling similarly.

Donald Trump's victory and the Republican takeover of the U.S. Senate (the U.S.House majority was undecided when this issuewent to press) will undeniably shape the negotiations. But neither party made the approaching fiscal cliff a major issue during the run-up to the election, and there is not a unified position on either side of the aisle. Many Republicans and Democrats are on the record as supporting an extension of the lower TCJA rates for most taxpayers, but there are those who disagree. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.), for example, has called for Democrats to allow the TCJA to expire in full. Meanwhile, some figures on the so-called New Right have suggested that Republicans should allow the individual tax cuts to expire and should partially undo the corporate tax changes made in 2017 to hike taxes on businesses.

Fiscal realities may bite too. When the TCJA passed, analysts projected that it would add to the budget deficit and national debt—and it did. But those problems were more easily waved away when the country was running significantly smaller annual deficits and the debt-to-GDP ratio wasn't reaching levels unseen since the height of World War II.

A full extension of the TCJA would add another $4.6 trillion to the deficit over the next 10 years, the Congressional Budget Office projects. When the economic benefits of lower taxes are taken into account, the extension would still reduce revenue by $3.5 trillion, according to an estimate by the Tax Foundation, a right-leaning think tank. With current deficits already approaching $2 trillion annually, lawmakers must now face the disconnect between how much government Americans are getting vs. how much they are paying for.

Ideally, Congress would offset the continued tax cuts with spending reductions. In reality, that's borderline impossible, since much of the expected spending growth over the next decade is for entitlement programs running on autopilot and mandatory interest payments on the debt that's already accumulated.

If spending cuts don't happen and the appetite for more borrowing is limited, then taxes simply must increase. But who should shoulder that burden?

The individual tax rates and brackets are only a part of that arithmetic. Lawmakers will also have to decide whether to retain the TCJA's cap on the state and local income tax deduction. Removing that would benefit wealthy taxpayers in high-tax locales like New York and California while adding to the deficit. The elimination of that tax credit, on the other hand, could net $2 billion in revenue over 10 years.

Similarly, they must decide how to handle the child tax credit, which was made more generous by the TCJA. Simply extending the child tax credit in its current form would cost an estimated $600 billion over a decade. Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle want to expand it again, but providing a greater benefit to families means requiring others to pay more (or adding yet more to the deficit).

It would have been useful to have the 2024 election season focused on candidates' tax and spending proposals so voters would be more keenly aware of the coming fiscal cliff and the difficult tradeoffs necessary to navigate it. That didn't happen, but there are at least a few broad, competing visions being sketched out by tax-focused think tanks.

On the left, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) stresses that high-income earners should see their tax rates revert to the pre-TCJA levels. Allowing the lower rates to expire for taxpayers earning over $400,000 annually would avoid more than 40 percent of the full cost of extending TCJA's policies, according to the group's calculations. The CBPP is also pushing for raising the corporate income tax to offset the maintenance of lower personal income tax rates.

The Tax Foundation, meanwhile, warns against using higher taxes on corporations or wealthy individuals as a tool to "pay for tax breaks for some at the expense of economic growth for all." The group is also skeptical of plans to use tariff revenue to offset tax breaks, since those tariffs would create a variety of economic harms—and would end up being paid by Americans anyway.

Optimistically, one might view this fiscal cliff as an opportunity for Congress to bring deficits under control and restructure Americans' fiscal relationship with the federal government. But it is also a messy tangle of overlapping political and policy intentions, one that would be difficult to solve even in an era when Congress was less fractured and more serious about policymaking.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Taxpocalypse."

Show Comments (54)