Alabama Pastor Can Sue the Cops Who Arrested Him For Refusing To Show His ID

A federal judge rejected the officers' claims of qualified immunity.

A federal judge is allowing a lawsuit to go forward against the Alabama cops who arrested a pastor as he was watering his neighbor's flowers.

The officers were apparently confused about Alabama's "stop and identify" law. The statute, which has already led to similar lawsuits, allows police to demand that individuals provide their name, their address, and an explanation of their actions when there is "reasonable suspicion" that they are committing a crime. Officers frequently use the law as a pretext to demand that someone hand over a physical ID card, even though a physical ID has significantly more information than people are required to give under the law.

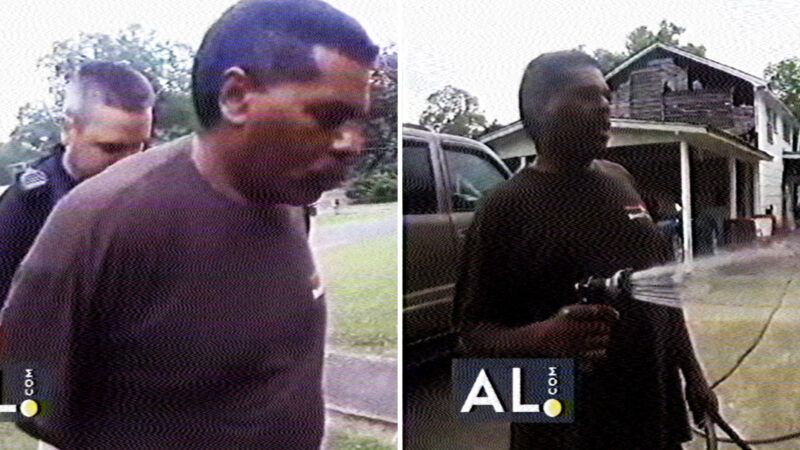

On May 22, 2022, Michael Jennings, a pastor at a church in Childersburg, Alabama, was watering his out-of-town neighbor's flowers when another neighbor called 911 to report a suspicious person. Two police officers, Christopher Smith and Justin Gable, soon arrived and began questioning Jennings.

Body camera footage of the incident shows that Jennings told the officers that his name was "Pastor Jennings" but refused to hand over his I.D. card, saying "I'm not gonna give you no I.D., I ain't did nothing wrong….I used to be a police officer."

"Come on man, don't do this to me. There's a suspicious person in the yard, and if you're not gonna identify yourself—" said one of the officers, before Jennings interjected, "I don't have to identify myself."

The officers arrested Jennings, and he was booked at the Childersburg City Jail on obstruction of government operation charges. The charges were dropped just days later, and he then sued, claiming that the officers wrongfully arrested him and violated his constitutional right to be free from unreasonable search or seizure.

Last December a judge dismissed the suit, ruling that the officers had qualified immunity, protecting them from civil liability. (Qualified immunity is the doctrine that shields officials from federal civil rights claims unless their alleged actions violated "clearly established" law, with "clearly established" defined extremely narrowly.) But Jennings appealed, and last Friday a three-judge panel for the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the decision.

The court's decision concluded that the police didn't even have "arguable" probable cause to arrest Jennings. The court not only dismissed the officers' claim that Jennings intimidated and physically interfered with their investigation of the 911 call, but it pointed out that the officers' claim that Jennings violated Alabama's ID law was obvious nonsense.

Even if the officers had a right to demand Jennings identify himself, Jennings still complied with the state's ID requirements. He told the officers who he was, that he lived across the street, and why he was in his neighbor's yard.

"While it is always advisable to cooperate with law enforcement officers," the opinion reads, "Jennings was under no legal obligation to provide his ID. Therefore, officers lacked probable cause for Jennings' arrest for obstructing government operations because Jennings did not commit an independent unlawful act by refusing to give ID."

With the court's decision, Jennings can continue suing the officers who wrongfully arrested him. But it shouldn't have taken this intervention for Jennings to be able to lodge his lawsuit in the first place. Stringent qualified immunity protections made police officers—and other government actors—virtually unaccountable for violating citizen's rights. The fact that Jennings' clear-cut case was dismissed in the first place reveals the deep flaws in that system.

Show Comments (30)