He Immigrated to the U.S. as a Child. He Was Just Kicked Out—Despite Coming Here Legally.

"Documented Dreamers" continue to have to leave the country even though this is the only home many have ever known.

Roshan Taroll says his mother, Beena Preth, brought him to the United States as a child in hopes he would put his nose to the grindstone and shoot his shot at accessing the bounty of opportunity uniquely offered by America. He will not have the chance.

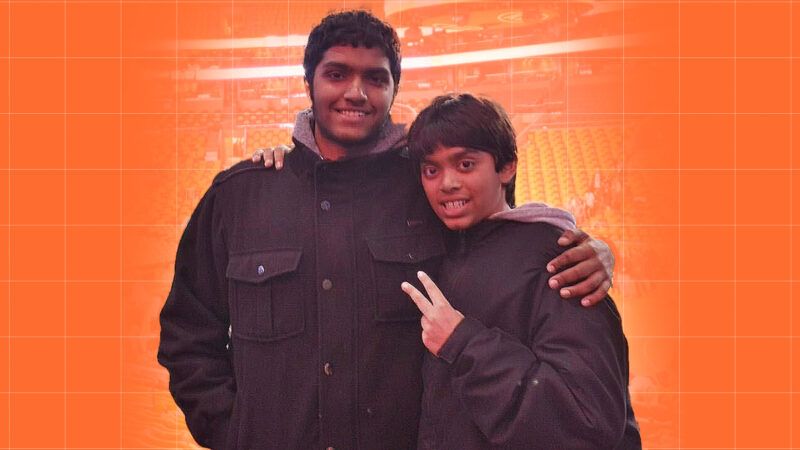

In 2008, Taroll arrived in the U.S. as a 10-year-old with his younger brother and Preth, who had secured a job in the States at a tech company on an H-1B visa. He subsequently became a Dreamer: the moniker given to migrants who arrived in the U.S. as children through no fault of their own.

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), instituted during President Barack Obama's administration, shielded many of those individuals—who often do not know any other country as home—from deportation. But core to being a Dreamer under DACA's purview is that you must be undocumented.

Taroll* and about 250,000 others, meanwhile, are known as "Documented Dreamers": those who came to the U.S. as children lawfully but face self-deportation if their parents cannot help them get a green card, or if they cannot find another visa, before they age out of dependent status at 21 years old. DACA does not apply to them, so in many cases, Documented Dreamers are vulnerable to expulsion not in spite of coming to the U.S. legally—but because of it.

One typical reaction: These migrants must not have done their due diligence in trying to obtain permanent residence; they came here as kids, so they had plenty of time.

It's a core misconception that obscures how topsy-turvy the U.S. immigration system is. It can take decades—or more—to get through the green card application process, thanks to stratospheric wait times wrought by country-of-origin caps.

The federal government allots approximately 140,000 employment-based green cards annually. But each country can nab a maximum of 7 percent of those in a single year, meaning people from nations that produce a disproportionate amount of highly skilled immigrants are punished based on where they were born. And thus the backlog was born.

India, where Taroll is originally from, is a prime example. There are about 1.8 million cases in the backlog. Over one million of those are from India, and they are waiting in a line that continues growing longer and longer with little hope in sight. Many will wait decades. Most perverse is that that is essentially the best-case scenario, as new applicants today now face a wait time that requires defying mortality: about 134 years. Hundreds of thousands will die waiting.

Taroll's mother was one of them. In 2018, Preth died of cancer before she could make it to the front of the line. Although the federal government allows family members to apply for permanent residence after their principal petitioner dies, that hope was more theoretical than practical, as Taroll predictably aged out of dependent status before he, too, could reach the front of the line. He subsequently converted to a student visa to finish his degree at Boston College and then received a temporary work permit allotted to international students who graduate with science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) degrees. His employer, a semiconductor company, submitted Taroll in three H-1B visa lotteries, of which the odds of winning have dropped off a cliff in recent years. He wasn't selected.

So last month, Taroll was forced to self-deport to Taiwan, where his employer was able to secure him a spot. He does not know the language nor does he have any family ties to the country. "I grew up in my hometown of Boston as just a regular kid, never imagining that my status would define my decisions later in life," he tells me. "And like many Documented Dreamers, we only truly understood the ramifications once we get closer to aging out and have to start planning for ways to remain in the only country that we know as home."

Though the architecture of the law doomed Taroll's chances at getting permanent residence from his mother, some Documented Dreamers never have any such hope to begin with, as certain visas do not have pathways to permanent residence or citizenship. In 2005, Laurens van Beek's parents moved him from the Netherlands to Iowa on an E2 small business visa, which allows for extensions so long as they meet certain requirements.

It does not, however, allow them to get in line for a green card. Van Beek attended the University of Iowa on an international student visa and, like Taroll, received a temporary extension based on his studies in STEM. But in 2022, after three failed H-1B visa lottery attempts, he had no choice but to leave the country. At the time of his expulsion, van Beek says, his father—who remained in Iowa to run his small business, Jewelry by Harold—was suffering from grave kidney disease. "I believe DACA is a good thing," van Beek tells me, "however why are these protections not extended to Documented Dreamers as well? Or at least something to prevent us from having to give up our lives and roots?"

Some lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have tried to answer that question. In 2021, Rep. Deborah Ross (D–N.C.) introduced a bill in the House to effectively close the Documented Dreamer loophole and pave a pathway for citizenship. It also would have addressed another one of the more harebrained inconsistencies with DACA, whose recipients can apply for work permits. Documented Dreamers cannot. "When I was a freshman and sophomore, I didn't go to any of the career fairs," Documented Dreamer Pareen Mhatre told me in 2021, "because I knew that I wouldn't be able to apply for any of the internships."

That same legislation was introduced in the Senate by Sens. Alex Padilla (D–Calif.) and Rand Paul (R–Ky.). "My bill America's Children Act fixes the documented dreamer problem by prioritizing the children of legal immigrants for permanent status," Paul tells Reason. "So, a child whose parents came legally will not have to face deportation when they turn twenty-one."

In 2022, it looked like change was nigh. A version of that bill passed the House as an amendment in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). And then it was laid to rest in the Senate's legislative graveyard after Sen. Charles Grassley (R–Iowa) rebuffed the proposal. So the change, despite being widely uncontroversial and not rupturing along predictable partisan fault lines, remains paralyzed for now. "Comprehensive immigration reform has become the enemy of incremental reform," adds Paul.

The momentum isn't dead. In June, Padilla and Ross submitted a bipartisan letter, signed by 43 lawmakers, urging President Joe Biden's administration to make the plight of Documented Dreamers less tenuous via executive action, although a legislative solution is by far the superior option, should Congress find the political will to do its job. "Every day without action results in young adults, who have been lawfully raised in the United States by skilled workers and small business owners, to be forced to leave the country, separating them from their families and stopping their ability to contribute to our country," says Dip Patel, founder of Improve the Dream, a group that advocates for Documented Dreamers. "The economic case is clear and the moral case is clear. It is common sense."

Taroll is just one such casualty. He still hopes he'll get a different ending. "This country means everything to me and I owe everything to it," he says. "While I always say that my parents raised me and my brother, I also believe that this country raised us. It afforded us the opportunities to participate academically, personally, and professionally. We always saw it as home and as a duty always made sure to leave our positive mark on it." Van Beek agrees: "My current hope is that my employer is able to secure a visa for me to come back to the United States," he tells me, "but in the meantime I'm doing my best to stay positive."

Both also have strong familial reasons to return to the U.S., albeit in different ways. Van Beek's father "is not in the best medical state," he says, but he survived—after one of his employees donated her kidney to save him. Taroll's mom, meanwhile, has been gone for over six years. But he still wants to come back for her. "All she wanted was for me and my brother to work hard and have a chance at the American dream," he says. "It feels as though I am letting her down by not fulfilling her one wish."

*CORRECTION: The original version of this article partially mischaracterized Taroll's relationship to DACA.

Show Comments (85)