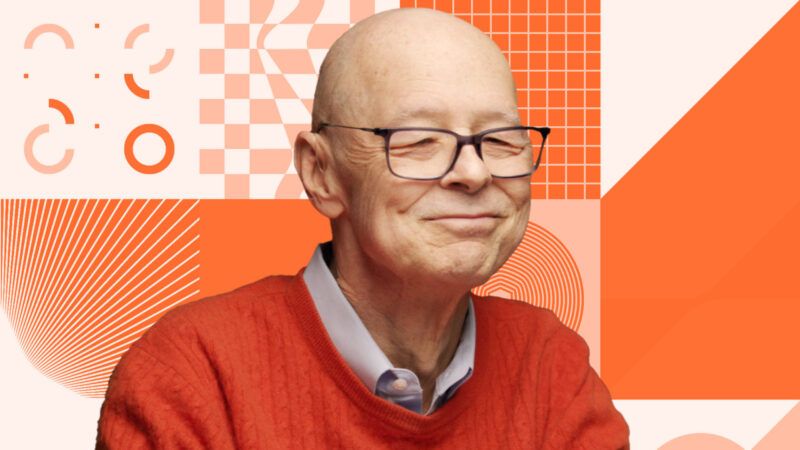

David Boaz, RIP

The longtime Cato Institute executive vice president was one of his era's most effective explainers of libertarianism.

David Boaz, longtime executive vice president at the Cato Institute, died this week at age 70 in hospice after a battle with cancer.

Boaz was born in Kentucky in 1953 to a political family, with members holding the offices of prosecutor, congressman, and judge. He was thus the type "staying up to watch the New Hampshire primary when I was 10 years old," as he said in a 1998 interview for my book Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement.

In the early to mid-1970s, Boaz was a young conservative activist, working on conservative papers at Vanderbilt University, where he was a student from 1971 to 1975. After graduation, he worked with Young Americans for Freedom (YAF), in whose national office he served in various capacities from 1975 to 1978, including editing its magazine, New Guard.

In the 1970s, he recalls, YAF saw themselves as not merely College Republicans but were instead "organized around a set of ideas." When he started with YAF he already thought of himself as a libertarian but saw libertarianism "as a brand of conservatism. But during my tenure at YAF, as I got to know people in the libertarian movement, I came to believe that conservatives and libertarians were not the same thing and it became uncomfortable for me to work in the YAF office."

Now fully understanding libertarianism as something distinct from right-wing conservatism, "I badgered Ed Crane to find me a job and take me away from all this." Boaz had met him when Crane was representing the Libertarian Party (L.P.) at the Conservative Political Action Conference in the mid-'70s and kept in touch with him when Crane was running Cato from San Francisco from 1977 to 1981. Via his relationship with Crane, Boaz became one of two staffers on Ed Clark's campaign for governor of California in 1978, which earned over 5 percent of the popular vote. (Clark was officially an independent because of ballot access requirements but was a member of the L.P. and ran with L.P. branding.)

Boaz then worked with the now-defunct Council for a Competitive Economy (CCE) from 1978 to 1980, which he described as "a free market group of businessmen opposed not only to regulations and taxes but to subsidies and tariffs…in effect it was to be a business front group for the libertarian movement." He left CCE to work on Ed Clark's 1980 L.P. presidential campaign, where Boaz wrote, commissioned, and edited campaign issue papers as well as the chapters written by the various ghosts for Clark's official campaign book. Boaz also did speech writing and road work with Clark.

The campaign Boaz worked on earned slightly over 1 percent, 920,000 total votes—records for the L.P. that were not beaten until Gary Johnson's 2012 run (in raw votes) and 2016 run (in percentages). "The Clark campaign was organized around getting ideas across in a way that is not outside the bounds of what was politically plausible," Boaz reminisced in a 2022 interview. "When John Anderson got in [the 1980 presidential race as an independent], we recognized he was going to provide a more prominent third-party choice, maybe taking away our socially liberal, fiscally conservative, well-educated vote, and he ended up getting 6 percent. We just barely got 1 percent. And although we said, 'This is unprecedented, blah blah,' in fact we were very disappointed."

Boaz began working at the Cato Institute when it moved to D.C. in 1981, where he became executive vice president and stayed until his retirement in 2023. He was Cato's leading editorial voice for decades, setting the tone for what was among the most well-financed and widely distributed institutional voices for libertarian advocacy. Cato, with Boaz's guidance, provided a stream of measured, bourgeois outreach policy radicalism intended to appeal to a wide-ranging audience of normal Americans, not just those marinated in specifically libertarian movement heroes, styles, and concerns.

Boaz was, for example, an early voice getting drug legalization taken seriously in citadels of American cultural power with a forward-thinking 1988 New York Times op-ed that concluded presciently: "We can either escalate the war on drugs, which would have dire implications for civil liberties and the right to privacy, or find a way to gracefully withdraw. Withdrawal should not be viewed as an endorsement of drug use; it would simply be an acknowledgment that the cost of this war—billions of dollars, runaway crime rates and restrictions on our personal freedom—is too high."

Boaz wrote what remains the best one-volume discussion of libertarian philosophy and practice for an outward-facing audience, one that while not losing track of practical policy issues also provided a tight, welcoming sense of the philosophical reasons behind libertarian beliefs in avoiding violence as much as possible to settle social or political disputes, published as Libertarianism: A Primer in 1997.

Boaz's book rooted its explanatory style in the American founding, cooperation, personal responsibility, charity, and uncoerced civil society in all its glories. He explained the necessity and purpose of property, profits, entrepreneurship, and how liberty is conducive to an economically healthy and wealthy society, and how government interferes with the growth-producing properties of the system of natural liberty. He discusses the nature and excesses of government in practice and applies libertarian perspectives to many specific policy issues: health care, poverty, the budget, crime, education, even "family values." Boaz's book is thorough, even-toned, erudite, and thoughtful and intended for mass persuasion, not the sour delights of freaking out the normies with your radicalism.

Meeting Boaz in 1991 when I was an intern at Cato (and later an employee until 1994) was bracing to this wet-behind-the-ears young libertarian who arose from a more raffish, perhaps less civilized branch of activism. As a supervisor and colleague, Boaz was a civilized adult, stylish, nearly suave, but was patient nonetheless with wilder young libertarians, of whom he'd dealt with many.

His very institutional continuity—though it was barely two decades long at that point—was influential in a quiet way to the younger crew. It imbued a sense that one needn't frantically demand instant victory, no matter how morally imperative the cause of freedom was. Boaz's calm sense of historical sweep both as a living person and in his capacious knowledge of the history of classical liberal ideas was an antidote to both despair and opportunism for the young libertarians he worked with.

His edited anthology The Libertarian Reader: Classic & Contemporary Writings from Lao-Tzu to Milton Friedman—which came out accompanying his primer in 1997—was a compact proof of libertarianism's rich, long tradition, showing how it was in many ways the core animating principle of the American Founding and to a large extent the entire Enlightenment and everything good, just, and rich about the whole Western tradition. The anthology featured the best of libertarian heroes both old and modern, such as Thomas Paine, Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson, John Stuart Mill, Herbert Spencer, Lysander Spooner, and Benjamin Constant from previous centuries and Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, Ayn Rand, Murray Rothbard, and Ludwig von Mises from the 20th, as well as providing even wider context with more ancient sources ranging from the Bible to Lao Tzu. He also placed the libertarian tradition rightly as core to the fights for liberation for women and blacks, with entries from Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Angelina and Sarah Grimké.

Asked in 1998 why he chose a career pushing often unpopular and derided ideas up a huge cultural and political hill, Boaz told me: "I think it's satisfying and fun. I believe strongly in these values and at some level I believe it's right to devote your life to fighting for these values, though particularly if you're a libertarian you can't say it's morally obligatory to be fighting for these values—but it does feel right, and at some other level more than just being right, it is fun, it's what I want to do.

"I like intellectual combat, polishing arguments, and I also hate people who want to use force against other people, so a part of it is I am motivated to try to fight these people. I wake up listening to NPR every morning and my partner says, 'Why do you want to wake up angry every morning?' In the first place, I need to know what's going on in the world, and in the second place, dammit, I want to know what these people are up to! It's an outrage what they're up to and I don't want them to get away with it. I want to fight." For decades, at the forefront of the mainstream spread of libertarian attitudes, ideas, and notions, David Boaz did.

Show Comments (30)