Rent Free Q&A: Bryan Caplan on Build, Baby, Build

The George Mason University economist talks about his new housing comic book and how America could deregulate its way into an affordable urban utopia.

People write and write and write about the need to deregulate housing construction, and yet some days it seems like minimal progress is being made. Perhaps Yes In My Backyard (YIMBY) reformers would be better off drawing the argument against zoning instead.

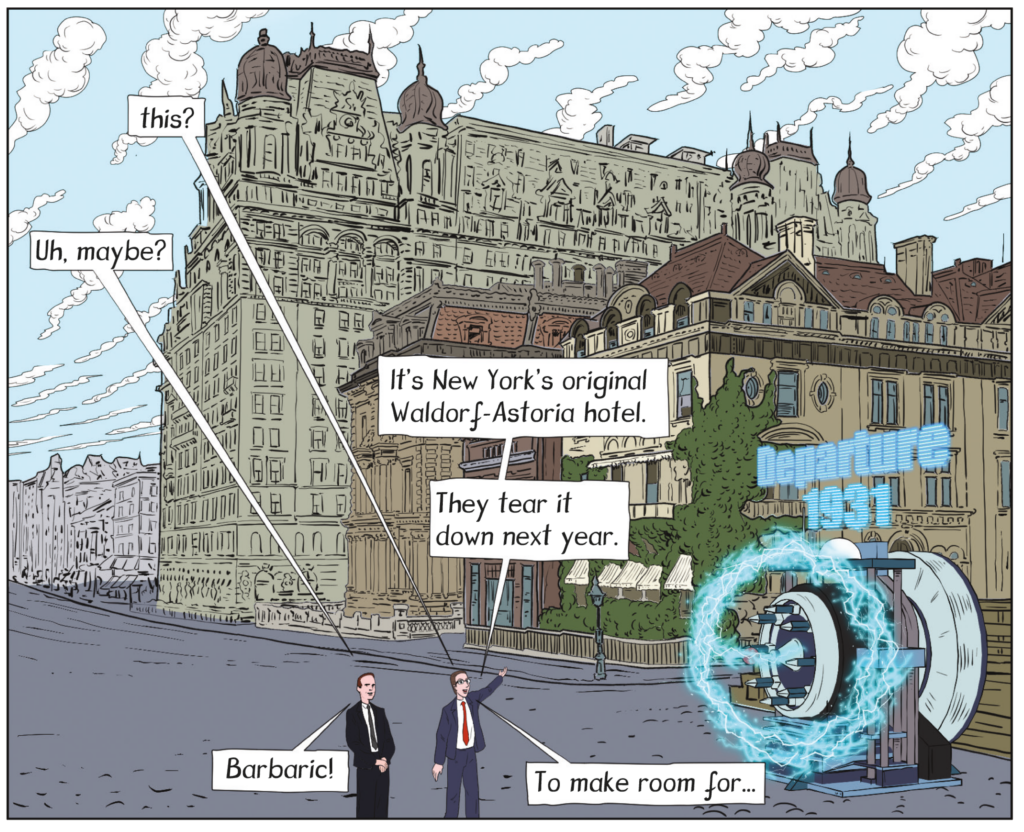

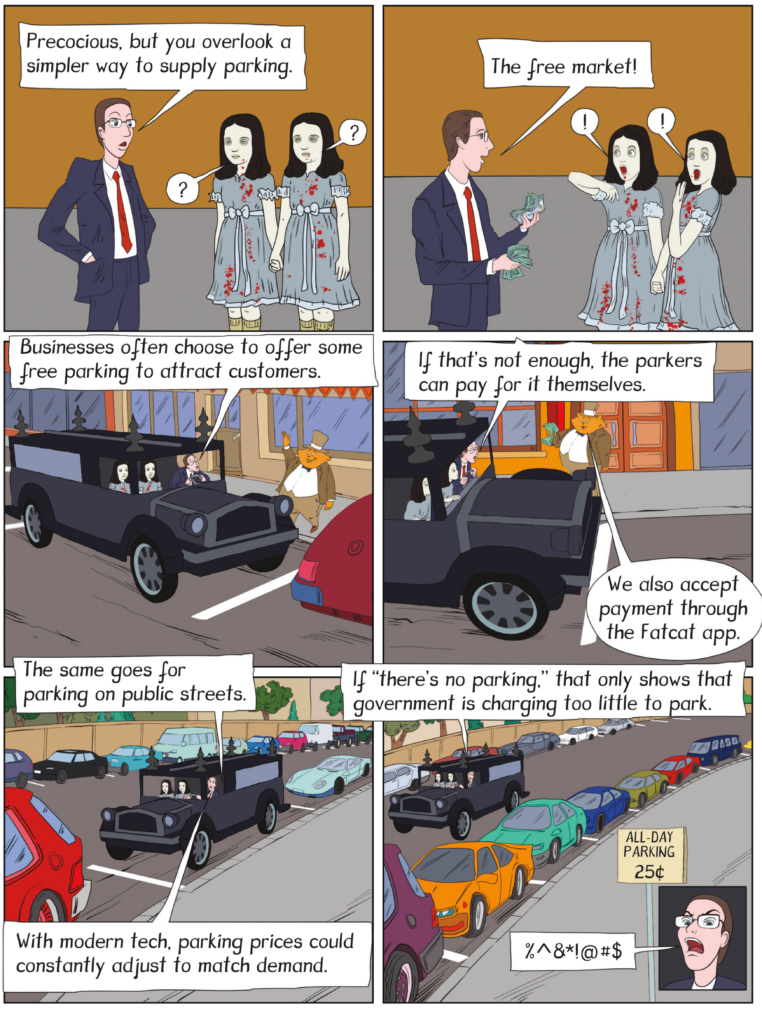

That's certainly the view of George Mason University economics professor Bryan Caplan. His new comic book Build, Baby, Build: The Science and Ethics of Housing Regulation makes the illustrated case for eliminating basically all restrictions on building new homes.

This is Caplan's second comic book. His first, 2019's Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration, made the radical libertarian case for eliminating all restrictions on immigration. Now Caplan and illustrator Ady Branzei do the same thing for housing.

In Build, Baby, Build, Caplan explains to readers why regulation makes housing so expensive, how building more of it would lower prices, and the tremendous knock-on benefits that would flow from more affordable shelter.

Rent Free Newsletter by Christian Britschgi. Get more of Christian's urban regulation, development, and zoning coverage.

The book is a surprisingly thorough treatise on how America, with some serious deregulation, could build its way out of its seemingly most intractable problems. The occasional appearance of a city-wreaking Not In My Backyard (NIMBU) Uncle Sam and a deregulation-loving Dracula makes it a breezy and entertaining read for people who otherwise don't care much about debates over minimum lot sizes.

For this week's edition of Rent Free, I talked to Caplan about why he decided to make the YIMBY case in comic form, why abolishing zoning really is a panacea, and why even selfish NIMBYs should love more home construction.

Q: Why make the case for more housing in a graphic novel form? What do you think that adds to the argument?

A: There is so much high-quality research out there on the topic and yet, almost no one would ever read it because most of it is really boring. Which means that I look at this bounty of knowledge that we've got and I'm just sitting there saying, "How could I communicate this to anyone else in the world?" Honestly, I'm just looking for some way of getting other people interested. The main pitch that I've been giving for this book when someone just gives me 20 seconds is, "I've written the most fascinating book that has ever been written on housing regulation."

Q: You make the strong case that ending zoning and most building regulations is a panacea that will solve so many of our problems. Why that is?

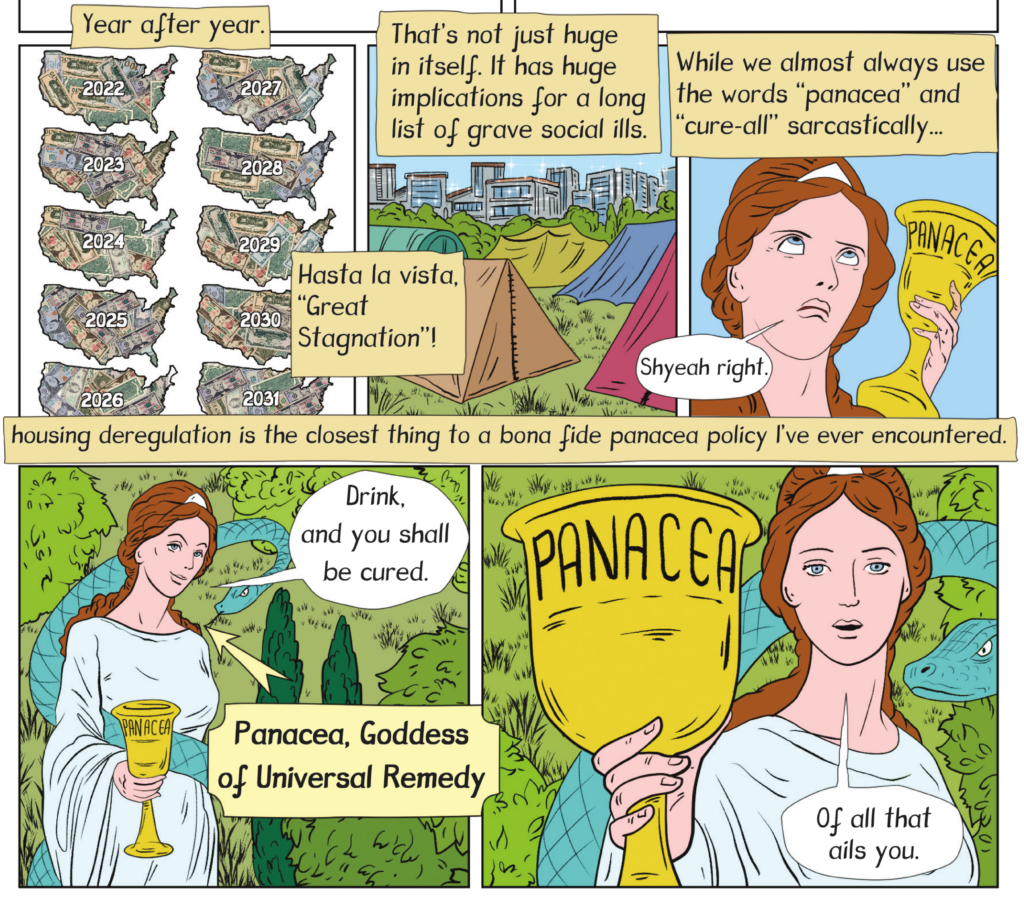

A: I am careful to not say "solve" because solve sounds like 100 percent. What I will say is it's like a panacea because it makes a big dent in a bunch of problems that often we think of as just individually unsolvable. The idea that there's one policy that can go and work some magic on all of them simultaneously is hard to believe. But that is my story.

You've just got to go through issue by issue. I start off with the basics. Housing regulation has greatly inflated the price of housing and deregulation would get the price of housing back down. This is such a large part of the typical person's budget. Getting the price of housing down by 50 percent is not like getting the price of chewing gum down by 50 percent. It is making a big difference in the overall standard of living.

Once you realize that, then it's like, "Well, but it's not going to have equal effects on everybody, right?"

For people who are poor, they right now spend a larger share of their income on housing, so it's going to give them extra help. That's going to reduce inequality, which is another thing people talk about.

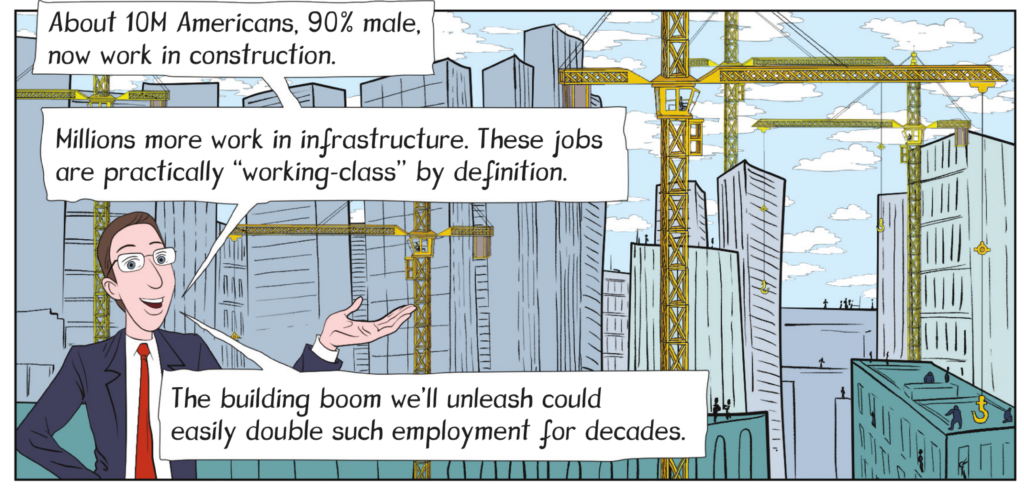

There would be a lot of additional employment for people in the construction industry, which is a demographic that has done really badly in the past few decades; non-college-educated males. Well, that's basically the main kind of people that work in the construction industry.

If you're really worried about non-college males and how they're faring and how they haven't really adapted well to a service sector economy or office jobs, here we've got a way to go and create a lot of additional traditional masculine, non-college jobs. And once again, because it is still a very large industry, this isn't just like doubling employment in chewing gum.

Do you want me to keep going on the list of problems or is that enough?

Q: Yeah, give me one more if you've got another one.

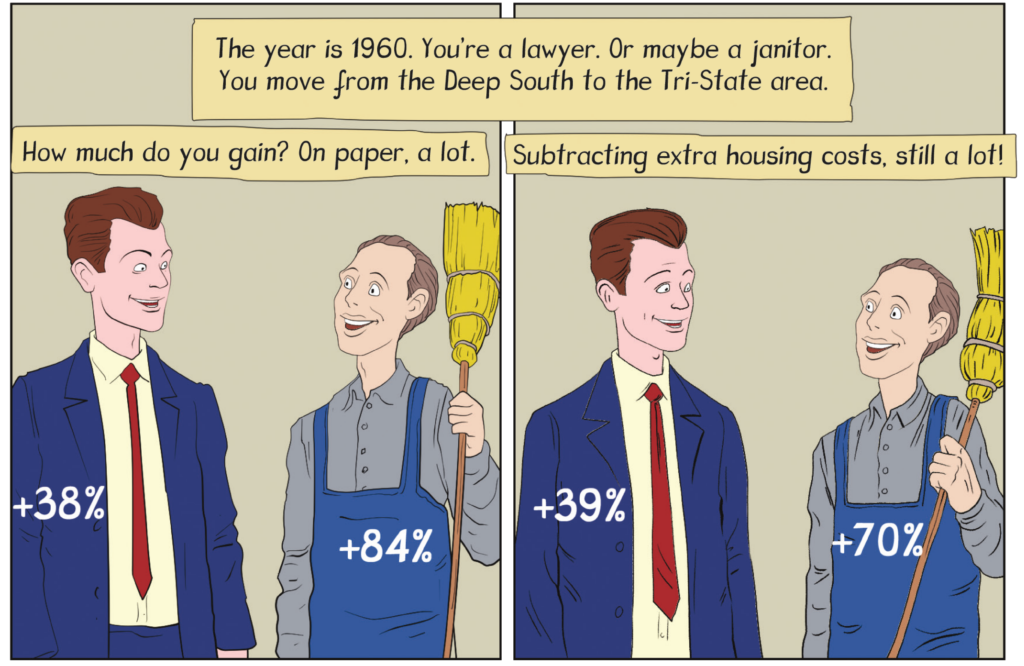

A: There's a traditional path of upward mobility that Americans used to have, which is just to move to the highest-wage parts of the country. This is pretty much foolproof.

You just say, "I'm going to leave the South and go to California," or "I'm going to leave the Midwest and go to New York City."

This doesn't work anymore because housing prices have gotten so high in what we call our gold rush areas of the country that they eat up more than 100 percent of the wage gains you get.

Right now, we have this weird, historically unprecedented situation where people are leaving high-wage areas to go to low-wage areas to get a worse job because the housing cost savings are so large, that they'll actually have a higher standard of living.

You can enhance not just equality, but social mobility by deregulating housing so that housing prices will be lower in the boom areas.

Q: Your last comic book was making the case for open borders. How much of a connection do you see between immigration and housing and the radical libertarian position on those issues?

A: The big connection is just this: If you measure how distorted the market is, the most distorted market is the international labor market. If you understand your basic economics, the more distorted the market is, the greater the gains are from deregulation. Housing is not as bad as the international labor market, but it's really bad.

We take a product that's a large share of people's income and we strangle it so that it's just really hard to lawfully do the things that are physically doable. That is just a big part of it.

These are policies that are so taken for granted that people don't even think of them as policy. People don't usually think about immigration restrictions. It's not really a policy, it's just a fact of life.

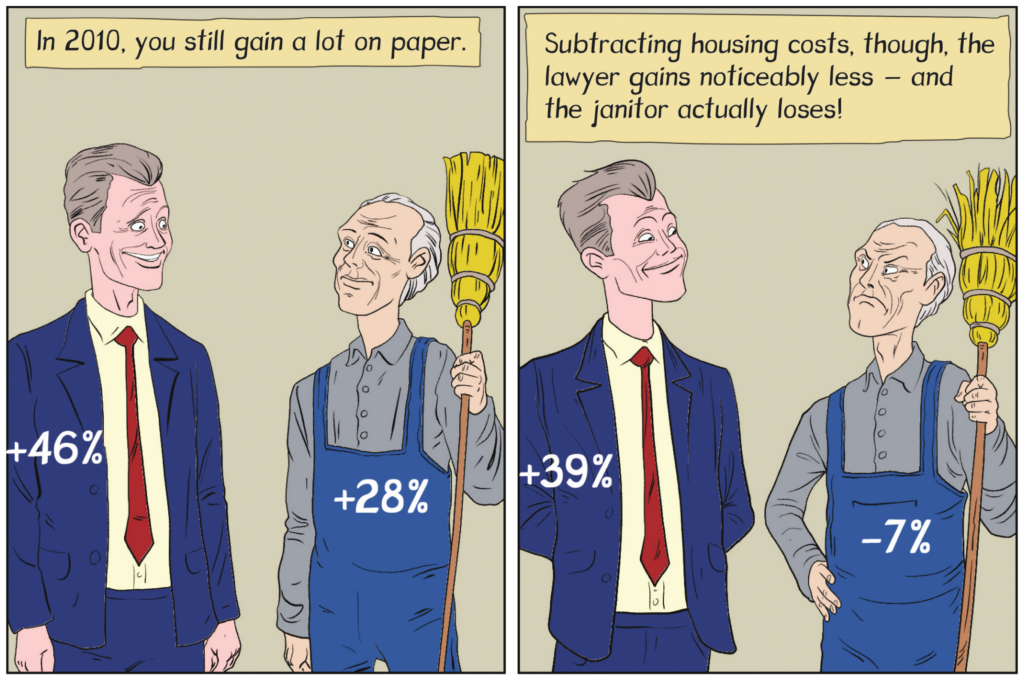

The same thing goes for housing regulation. You just walk around Central Park and look and you say, "Huh, there are a couple of skyscrapers here. Otherwise, the park is ringed by a bunch of buildings that are maybe six stories tall." Given the profitability of building skyscrapers here in a free market, they would just be demolishing hundreds of buildings and replacing them with skyscrapers.

Q: Your book presents big cities as bright, fun, futuristic places. How much of the case for cities rests on the aesthetic case and the economic arguments are secondary?

A: For me the economics is definitely primary. This is why I wanted to do this issue. But I was very mindful of the fact that for a lot of people, it's just the aesthetics that are bothering them.

I think most people can get used to a lot of different aesthetics, but the status quo bias is so strong that if you're used to things looking a certain way, not having skyscrapers around Central Park, then it's easy to convince yourself this is the only good way for things to look.

What I wanted to do in this book was to fight aesthetics with aesthetics and say, "Look, you're so convinced it's going to look bad. Let me get my artist to go and draw looking good, and maybe that will open up your mind."

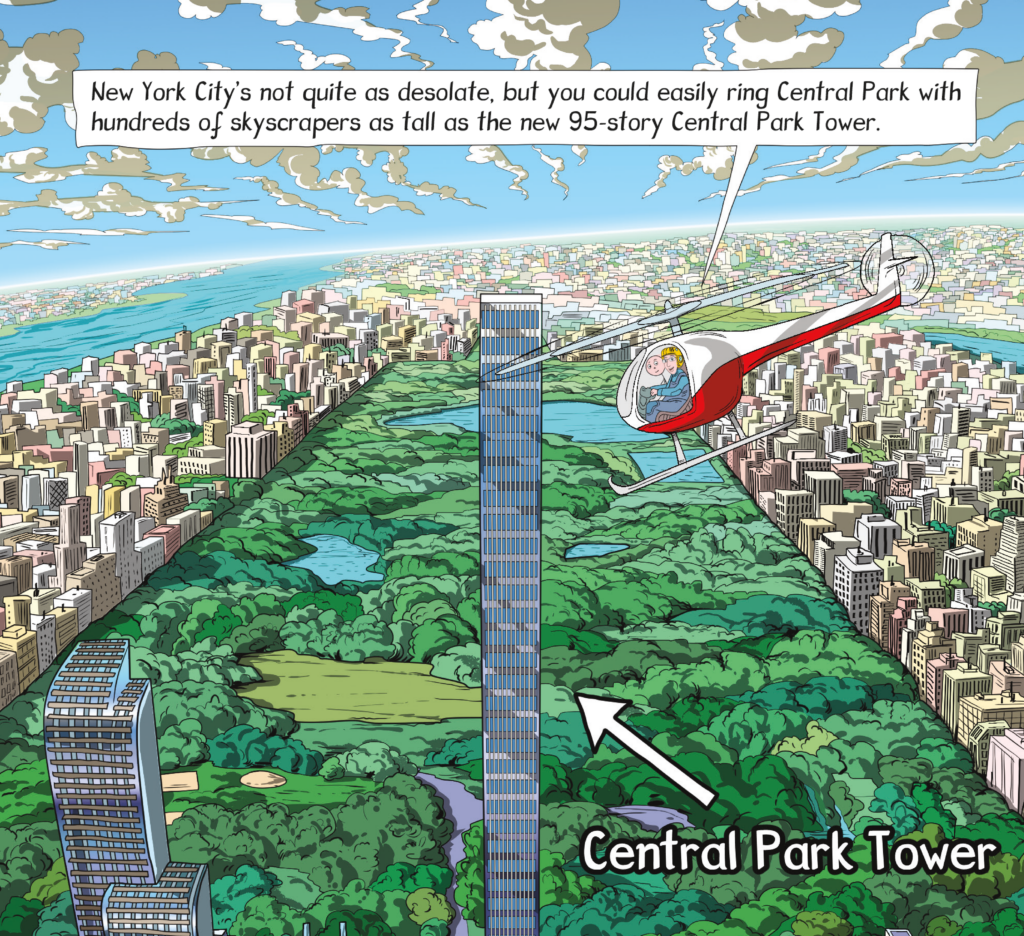

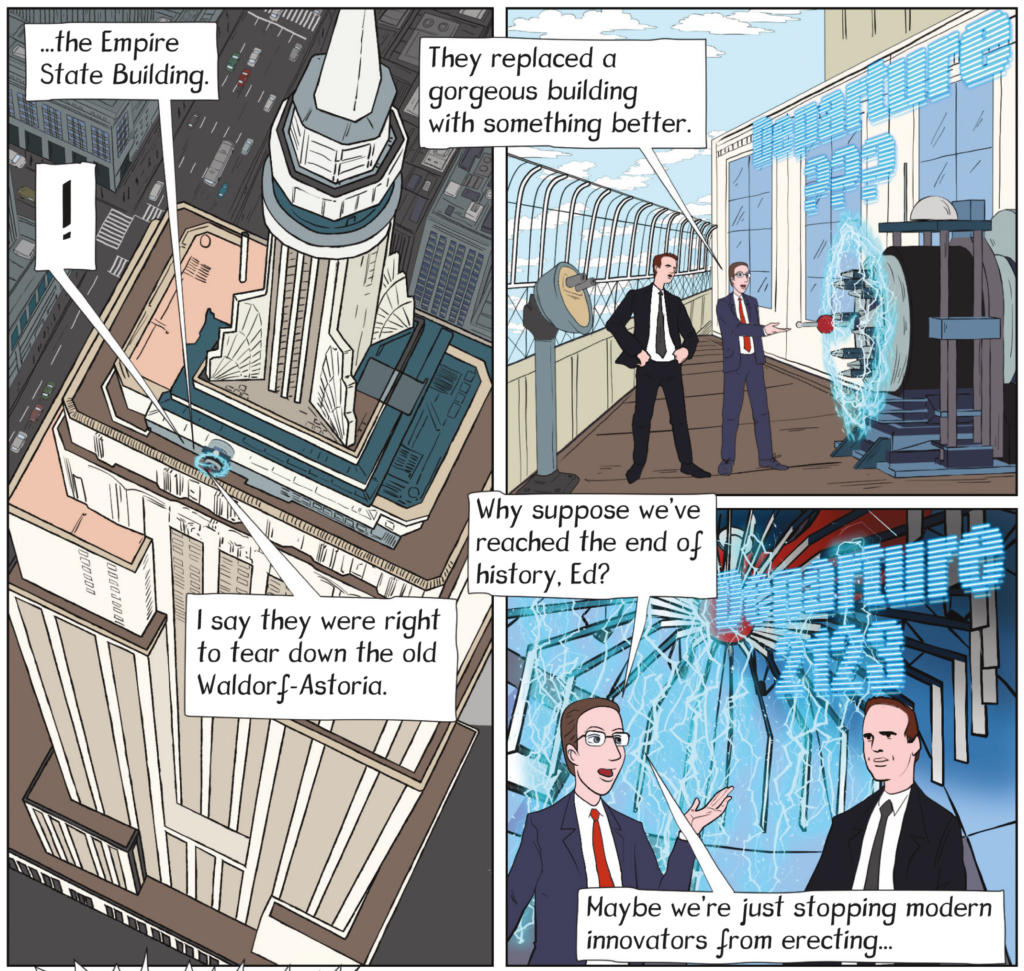

One of my favorite parts in the book is I am hanging out with [Harvard urban economist] Ed Glaeser and I've got a time machine and I take him back to New York City right before they build the Empire State Building and I show him the building that used to be there.

It was the original Waldorf Astoria hotel, and it's awesome. When you see this building, it's like you can't do better than that. And it's like, okay, well, let's go forward in the time machine. It's like two years later, all right, now what do you think? Okay, now this is the best building that could possibly be here.

I said, "Look, you should always be thinking about maybe when we knock down some historic building that people like, maybe we're building the history of the future." Maybe we're building something that people in the future will say, "That was really awesome." You don't need to be a Philistine about it and just say that, "I don't care what it looks like as long as people pay money for it."

Q: A common accusation you hear is that people who oppose new housing are just trying to selfishly prop up the value of their homes. You argue in the book that NIMBYs should support new housing out of self-interest. Why is that?

A: People's political views very reliably have almost nothing to do with their income or their station in life and almost everything to do with their high-level philosophy. If you think their high-level philosophy is just a smoke screen for objective self-interest, it just isn't.

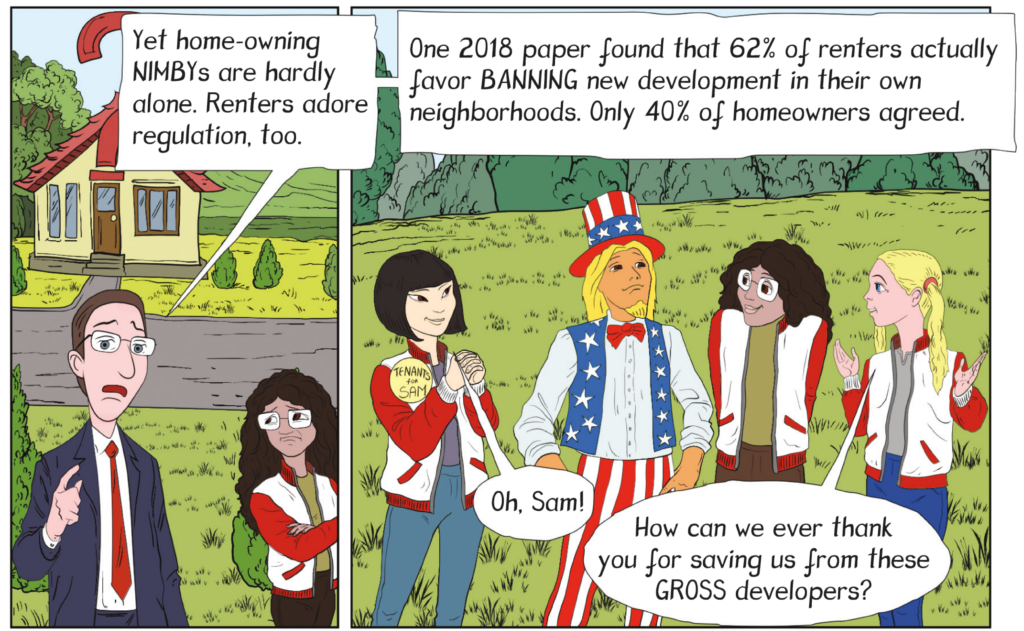

There's been research done on homeowners versus tenants and how supportive they are of new housing. Tons of tenants are against deregulation too. They are the people that bear the full cost of the regulation and they still do not believe [in deregulation]. Instead, they make the same arguments that homeowners do about neighborhood character, traffic, and parking.

There are actual experiments where they ask people to make predictions about what will happen when you allow more construction. The median answer in America is nothing. Roughly speaking, one-third say, if you allow new construction prices to go up, one-third say nothing happens, and one-third say they go down. It's the most basic economics in the world. And essentially two-thirds of the country just says, "No, no. I refuse to believe that."

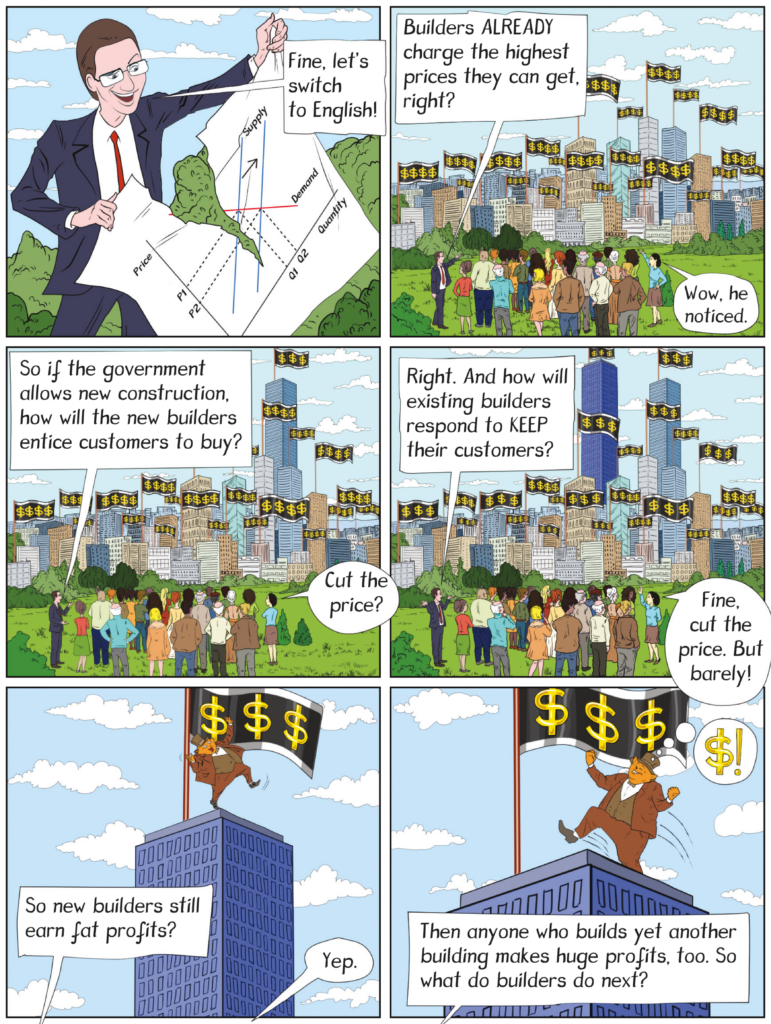

If you dig deeper, a lot of it is just like "I just refuse to believe that developers and landlords are going to be nice to people. Just because you let them build more stuff, doesn't mean they'll cut the price."

No economist ever said they're doing it to be nice. They said they're doing it to get customers. You cut the price when there's a lot of stock because if you don't cut the price, you can't sell it all. That's the correct story. Again, this is just not what is believed by most people.

Studies have shown that just telling people that developers will make a lot of money off of a project will dramatically reduce the support for it.

If it was really self-interest, we could take out our wallets and say, "How much money is it going to take to get you to agree [with housing deregulation]?"

It'd be that easy. You go to the people in your historic neighborhoods in San Francisco and say, "We'll pay double the price and then it'll be legal. Okay, fine, triple. Fine, five times."

There'd be some price where they would just say, "Sold and shut up." But that's not the way the real world works. It's more like a philosophy seminar.

If you imagine going to a philosophy seminar and just saying "How much money is it going to take to go and make this whole God issue go away?" It's like this is not an issue of money.

Q: Do you think that if we hadn't set up this system that lets people complain about new developments in public meetings, people wouldn't have these attitudes? Or is it natural that people don't like change?

I think it's an interaction between the two. I think that it is totally normal to have a bunch of complaints. But, it's also totally normal to not do anything about them.

Before housing regulation was important, people still were complaining. I just think they were complaining less because they just didn't feel as entitled to having a say on what everyone around them does. There was more of a sense of, "Well, I do what I want on my property. They do what they want on their property."

Of course, people complained before we had our current system of housing regulation. But in the earlier system, there just wasn't any real channel for the complaining. It was basically just, "Yeah, well. Too bad."

Now we have a lot of things we complain about, but they're not politicized and so we don't really think about it.

It's like what does the government do about the bad boyfriend situation? People complain about bad boyfriends all the time, but it's not like we have a Department of Boyfriend Analysis that will start licensing boyfriends. This is one thing where people just are like, "All right. Look, I'm going to complain." But it doesn't really register that the government could do anything about it.

Once you do create a whole system for going and taking complaints and allowing people to vent, then it does go and lead to a lot more action. It leads to the creation of people who are professional complainers—people who are especially neurotic and difficult.

Q: In the book, you go through the different intellectual traditions and how they should all support deregulating building. Why do you think people with such different views are coming up with the same policy solutions on this one issue?

A: My story is when the evidence is really strong, then it is just easy to go and make the case for the same policy from very different value premises. So, in that section, I go over the utilitarian, egalitarian, and libertarian views.

Then I also do the progressive view versus the conservative view. All of these can latch on to different benefits of the policy and say, "Those are my main arguments." And what I say is, "Look, you're all correct. These are all of your defenses. There's something to them. And if that gets you on board, great."

In a way I'm thinking if I just give people enough shrewd arguments, some of them are going to stick.

Q: The book is fast-paced, it's optimistic, it's forward-looking. Would you describe yourself as optimistic on this issue? Do you think the YIMBY case will meaningfully change policy?

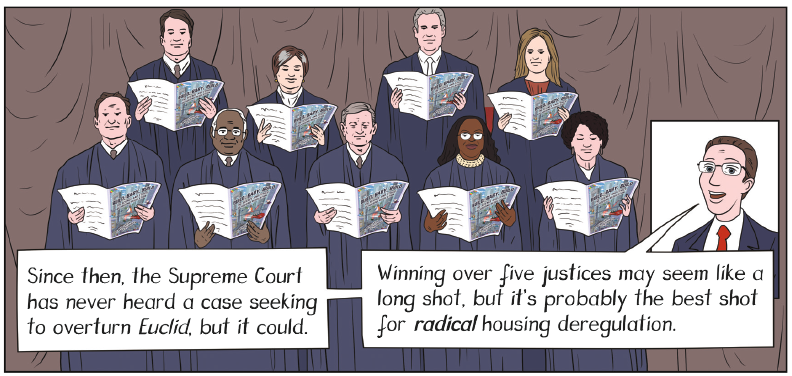

A: I'm a conditional optimist. The policy of [housing deregulation] will work wonders. I can't say that I'm really optimistic about it when coming anywhere close to winning. My prediction would be something like over the next 20 years, housing regulation will get 7 percent less bad. Of course, I love the idea that my book will start a political avalanche and everybody will read it and people wave it on the floor of Congress and 50 different state legislatures. There's actually a panel in the book where every Supreme Court justice is reading my book. I can dream.

At the same time, the fact that we got to where we are is a reason to think that the political system is really dysfunctional. I think the fundamental dysfunction is with the thinking of the typical voter.

Voters just are very innumerate. They're economically illiterate and honestly just paranoid. When I think about talking to people about development, I see bizarre apocalyptic scenarios they start painting as if they are fact. It's astounding to listen to.

I still remember in the late '80s, there was a new development a mile from my house that got approved and my dad was fuming when he came home from work. "Can you believe these corrupt politicians? They went and allowed this horrible development."

The funny thing is, 30 years later, I remember this argument and my dad had just completely forgotten it because things were fine. He stopped complaining because he had nothing to complain about once it happened. Whereas I sit there saying, "If people had listened to you it never would've happened and there would've been no concrete proof that you were wrong." You've got to green light stuff to show how ridiculous these fears are.

Q: In the book, you do give the NIMBYs their due by saying they're not necessarily wrong about traffic or parking or school capacity, but they are wrong to regulate building as a solution. How do you deal with legitimate concerns about development?

A: Absolutely. There's a really simple way to go and handle traffic: charge people for driving, especially when a lot of people want to drive! There's a really simple way to handle parking problems: charge people to park, especially when a lot of people want to park! What is the logic of saying it has to be free and then saying, and because it has to be free, we don't want people around here?

How about you just charge people and then that's your solution? When you regulate housing, there's so much collateral damage.

This interview has been condensed and edited for style and clarity.

Rent Free is a weekly newsletter from Christian Britschgi on urbanism and the fight for less regulation, more housing, more property rights, and more freedom in America's cities.

Show Comments (13)