RIP Marc Sandhaus, Whose Obsession With Cannabis Landraces Finally Bore Flower

The far-traveling smuggler turned breeder "never gave up" on his dream of recovering neglected marijuana strains.

The last time I heard from Marc Sandhaus was on Sunday, February 25, when he sent me a link to a Marijuana Moment article by Paul Armentano, deputy director of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, about the rescheduling of cannabis. The headline: "Is The Government Finally Abandoning Its Anti-Science Stance On Marijuana?"

It was an apt coda for Marc, who died five days later after a heart attack at the age of 73. Since the late 1960s, he had traveled a winding path from teenaged pot smoker in Los Angeles to federal marijuana defendant in Nevada to breeder of heirloom cannabis strains in Washington, which became the second state to legalize recreational use in 2012.

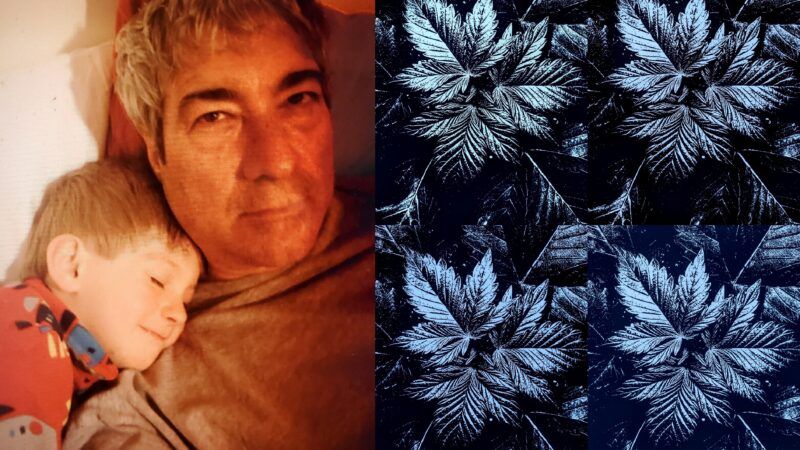

Marc was fascinated by the subject and determined to preserve and patent previously obscure cannabis landraces he had encountered during his wide travels. I knew him as a longtime Reason reader and inveterate tipster who inspired many of my blog posts over the years and generously supplied me with his vivid cannabis pictures, which he let me use as illustrations in exchange for nothing but a photo credit. His friends knew him as a kind, curious, loyal, and principled man who persevered despite daunting medical, professional, and legal challenges.

Brian Clancy, who met Marc when they were both teenagers living in Southern California, says they had an immediate rapport. "He was just a really nice, generous, affable" person who "loved to have fun and joke," Clancy says. "We all sat around and smoked cannabis, weed, marijuana—whatever we called it at the time—and we had a great old time. We instantly had a kind of connection because he was such a sensitive and good person…and an intelligent person, someone you could have a conversation with that wasn't just trivial."

Marc's interest in cannabis went beyond recreation. It became a livelihood at a time when there was no such thing as a state-licensed marijuana business, when anyone involved in that trade was a felon under state as well as federal law. In his emails to me, he repeatedly alluded to the federal marijuana indictment he faced in 1989, which included racketeering charges that could have sent him to prison for a very long time.

In Marc's telling, he "walked on all 38 counts" with the help of a skilled defense lawyer, former Nevada U.S. Attorney Lawrence Semenza II, because the government was "never able to prove one count." Marc said he ultimately pleaded guilty to one count of interstate or foreign travel in aid of racketeering, resulting in a modest fine. According to Clancy, "they put him in jail for about a year" before the charges were dismissed.

What was the nature of the alleged racketeering? The U.S. Attorney's Office in Nevada described it this way:

From early 1970 until approximately August 1993, a marijuana trafficking organization, some of whose members resided in Squaw Valley, California, was involved in the importation and distribution of over 60,000 kilograms of marijuana in the United States and the laundering of hundreds of millions of dollars. The organization operated principally between Southeast Asia and the west coast of the United States, and consisted of over 100 persons. It spanned seven states and 14 countries, including Nevada, California, Florida, Alaska, Colorado, Mexico, Canada, Hong Kong, Japan, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Costa Rica, Germany, Austria, Australia, the Cayman Islands, Panama, and Switzerland. It imported multiple tons of marijuana into the United States from Thailand.

That press release described Marc as one of the operation's "17 top level managers/organizers." Or as Marc put it: "You load 25 thousand kilos, what do you get? A 38 count RICO INDICTMENT."

Marc "was accused of being like a kingpin," Clancy explains. The operation, he says, involved "huge loads of cannabis coming from Thailand on big ships and then being offloaded into smaller ships throughout the Bay Area and Seattle, and along the Lost Coast of Northern California, which is where they got in trouble." One night, a cop noticed light signals between the boats and people on shore, and "they just rolled everybody up from the bottom towards the top, and the people folded on everybody."

Dave Barsky, another longtime friend, recalls that the Thai marijuana, known locally as "seaweed," came in "hundred-pound tins" that "were released from the mothership off the Northern California coastline to distract the attention of the authorities," which "worked pretty good." For a while.

Despite his grave legal jeopardy, Clancy says, Marc refused to testify against any of the other defendants, which "his moral compass" precluded. Washington marijuana activist Don Skakie—who met Marc in 2012 at Seattle's Hempfest, where Skakie was promoting the legalization of homegrown marijuana in Washington—likewise says Marc "would never give the other people up."

Marc "was never found with a single joint, one piece of marked money, any evidence whatsoever," Barsky says. "He was indicted on the testimony of three other people who were trying to avoid doing time."

After Marc was freed, his longstanding interest in photography led him to the business of selling Edward Curtis goldtones at an art gallery in Santa Fe. But his life was disrupted by a leg infection that nearly killed him and left him disabled. "He was doing quite well for himself until he became ill," Skakie says. "He had flesh-eating strep after walking in the mountains and went into a coma. And when he came out of that coma, it was so devastating to him personally and financially. I really don't think he ever recovered from that."

During the last six years of his life, when Marc lived on Skakie's property in Renton, Washington, he devoted much of his time to promoting neglected marijuana strains. He consulted with researchers such as Ethan Russo and marveled at a 2,000-year-old date palm seed that Israeli scientists had managed to germinate. "Marc never gave up on the hope and the belief that he could find some scientific way to bring [old cannabis strains] back," Clancy says, "or, if not, get the genetic code out of it."

Skakie, who tried a Nepalese strain that Marc recovered, says "there's nothing like the landrace—the original, uncrossed cultivars that really hold the original genetics of the plant." Marc was focused on "getting his genetics into retail," Skakie says, and looked into obtaining patents for those strains with an eye toward his two children.

"He really was very passionate" about the project because "he wanted to leave this legacy of these landrace seeds to his children," Skakie says. "He would've given them away for free if it wasn't for his children. He wanted to provide for his children. He always did. That was his true desire: to leave his children something from all of his adventures and travels and collecting those seeds."

Marc "traveled the world from Kerala, India, to Nepal, Mexico to Amsterdam, Jamaica, Hawaii, importing photography, folk art, and furnishings, smuggling cannabis genetics," says his friend Leslie Banionis. "He grew cannabis in most places he lived, preserving landrace seeds [and] cross-breeding modern cultivars for desired traits such as humulene, a terpene that ameliorates nausea secondary to pain."

Going through Marc's belongings after his death, Skakie was again struck by how much Marc "adored his children." Skakie came across "artwork going back to the second grade" and found that Marc had "kept every letter they ever wrote him."

Marc "was a very gentle soul, and he really loved living life," Skakie says. "He loved his children. He had faith in his fellow man, [believing] that a handshake still meant something in business."

Marc "loved his kids," Clancy says. "That was probably his number one thing that he would talk about if it wasn't cannabis."

Marc "was eternally interesting, though he fought depression," says his friend S. Rowan Wilson, who nicknamed him Eeyore. "We have no idea what will become of some of his landrace plants and info."

The conversations with Marc's friends were consistent with my impression of him as a reader who paid close attention to my work and frequently offered positive feedback along with links to useful information. In April 2021, he was excited about working as the "chief hybridizer" on a medical research project. "In 1989 I had a 38 count federal Racketeering Indictment for cannabis," he wrote. "Thai sticks, they allege. So if anyone truly appreciates what you are writing about cannabis, it's me."

Marc came of age at a time when most states still treated simple marijuana possession as a felony. By the time he died, 38 states had legalized marijuana for medical use, including two dozen, accounting for most of the U.S. population, that also allow recreational use. According to the latest Gallup poll, 70 percent of American adults favor legalization, up from 12 percent when Marc was smoking pot with Brian Clancy in Santa Monica. Marc did not live to see the end of federal marijuana prohibition, but it seems likely that I will.

After half a century of agitation, and despite the anti-pot backlash of the 1980s, marijuana reformers finally achieved the seemingly impossible dream of toppling prohibition, just as Marc's obsession with reviving cannabis landraces finally bore flower. Despite "all of the mishaps that happened to Marc," Clancy says, he "was always a very positive person who was always gonna get this to work. He never gave up."

Show Comments (3)