Hayao Miyazaki's The Boy and the Heron Is a Dream-Like Swan Song for a Great Animated Filmmaker

A magical, mysterious deeply personal movie about creation and legacy. And also, murder parrots.

I'll be honest: I'm not entirely sure I understood everything about The Boy and the Heron, famed Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki's latest—and likely last—film. But I am quite certain it's the best movie I've ever seen about giant talking murder parrots.

Like so many of his previous films, especially Howl's Moving Castle and Spirited Away, The Boy and the Heron plays like a strange dream faithfully depicted on screen. It's whimsical and magical and mysterious and personal, with a classic child's fantasy story structure that nods to both Alice and Wonderland and The Chronicles of Narnia without coming across as in debt to either. Which is to say that it's an animated children's movie, though it doesn't play quite like any kid's movie made in America in the last 30 years.

The Boy and the Heron starts in World War II era Tokyo when a boy named Mahito learns that his mother has died in a hospital fire. This early sequence, frantically rendered in harsh flames that char flesh and overtake the screen, grounds the movie in a deep sense of loss, a world where children must learn to deal with adult problems, whether or not they are ready. It's not gratuitous or graphic, exactly, but in its fiery immediacy, it's a far cry from the sort of soft, emotionally sanitized moments of personal pain that mark even the best American children's movies. It's a reminder of the way that children's stories, from the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Anderson, used to feature something more like real loss and terror, often mixed with strangeness and a sense of fundamental mystery about the world.

To be clear, Miyazaki isn't a hyper-realistic downer. A few years later, Mahito has moved to a country house to live with his father, who has remarried his wife's younger sister, Natsuko. At school he's bullied, but when not in class he explores the sprawling country estate. It's home not only to his father's factory, which makes cockpit tops for Japanese warplanes, but to a mysterious tower filled with books—and a bird, a heron, that seems to be its avatar.

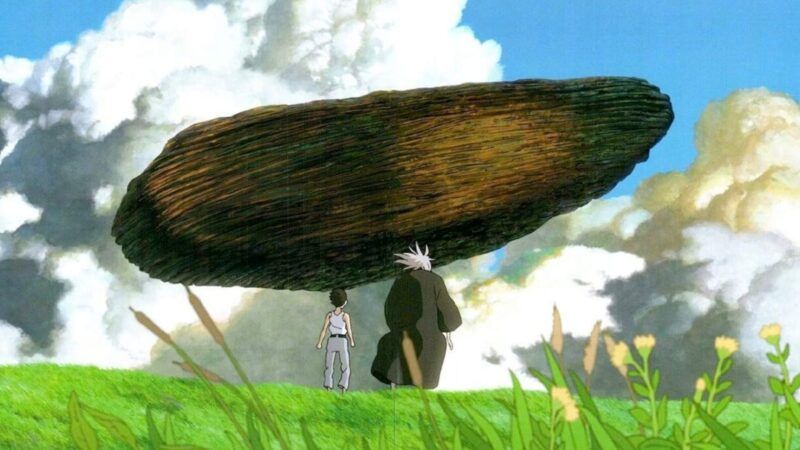

The heron begins to pester the boy, at first with uncanny interest, and eventually, by speaking to him. After Natsuko goes missing, the boy, the heron, and one of the estate's elderly maids, Kiriko, enter the tower and find themselves sinking into a strange and unfamiliar world.

Unfamiliar, that is, if you've never seen a Miyazaki movie: The Boy and the Heron exhibits the same sort of semi-spiritual animism as many of his previous works. As in Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away, Miyazaki has crafted a magical ecosystem that seems to work on its own hallucinatory logic. There are balloon-like nature sprites that become souls and sea birds that feast on the sprites as they make their way into the real world. And eventually, there are the murder parrots—squawking, knife-wielding, giant, multi-colored, talking, parrot people ruled by the Parrot King (amusingly voiced in the English dub by Dave Bautista).

If none of this quite makes sense when described, well, don't worry—it's not exactly crystal clear on screen either. The point of a film like Heron is not to find some concrete coherence, but to let the dreamlike imagery work its magic, and follow it wherever it leads.

That turns out to be a sort of time palace, ruled by an ancient king who happens to be Mahito's long-lost uncle, a brilliant man who spent all his time reading books but was always said to have gone mad before he went missing. The magical otherworld is his creation and his responsibility. But he hopes to pass on his duties of care to his young progenitor, keeping the world alive while allowing Mahito to make it his own.

The boy then faces a choice: Stay and be a caretaker of his brilliant relative's magical legacy? Or return to the real world, the land of war and suffering and ordinary living, and try to make a life there?

Miyazaki, now in his 80s, is probably the most important animated filmmaker of the last 40 years. His final work reckons with legacy and the end of a life defined by wondrous creation. It's a strange and beautiful swan song—or perhaps a heron song?—a bow from a great artist after a life well-lived.

Show Comments (3)