Shut Up Already About John Fetterman's Slob Chic

The Senate is an incompetent laughingstock regardless of what its members wear.

Was it really only last week that the biggest story blowing out of Washington, D.C., like smoke from a Canadian wildfire was the announcement that the Senate, the self-described "world's greatest deliberative body" (fact check: FALSE), would no longer enforce its "voluntary" dress code, thereby letting 100 of the luckiest bastards on the face of the Earth have even less to fret over?

And was it only late yesterday that the same legislators who couldn't be bothered to do any substantive work on the $6 trillion–something budget for the fiscal year that starts on October 1 rallied to pass a binding dress code (more on that in a moment)?

These things simultaneously seem like they happened sometime during the second Grover Cleveland administration and maybe 15 minutes ago. Such odd and intense minidramas about insignificant issues are the rule, not the exception, in contemporary politics, and leaders will do anything to avoid confronting serious issues, especially related to ballooning budgets (in nominal dollars, federal spending has more than tripled over the past 20 years).

Now more than ever, we live in a 24/7 doom-loop of the "Roth Effect," which holds that the world is getting ever weirder and less believable on an hourly basis. Certainly, no serious novelist would have scripted last night's GOP presidential debate, which sounded more like a Samuel Beckett play put on by middle schoolers than a meaningful discussion about the country's future.

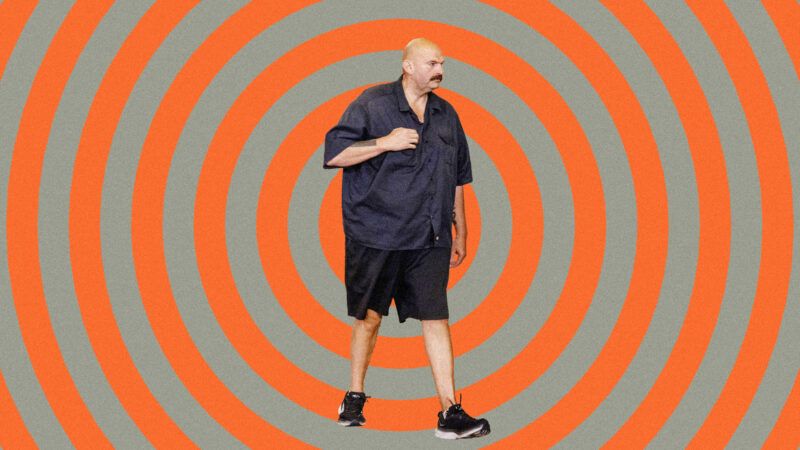

"Senators are able to choose what they wear on the Senate floor," Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D–N.Y.) told the Associated Press last week, which pointed out that lowly aides and support staff don't get the same freedom. The rule change was reportedly made for the benefit of Pennsylvania Democrat John Fetterman, who suffered a stroke during his 2022 campaign against crudité-apocalypticist Mehmet Oz and is widely known for dressing in cutoffs and hoodies or, as he puts it, "like a slob." Fetterman is the Rubeus Hagrid of the Senate, an oversized, sometimes genial, sometimes irascible character who uses "assistive technology" due to his ongoing medical issues and who once threatened to beat me up on Bill Maher's Real Time (it's all good between us, really). It wasn't exactly clear—even to Fetterman—why the change was necessary. "It's nice to have the option," he said, "but I'm going to plan to be using it sparingly." And yet, there he was, almost immediately presiding over the Senate in something less than a jacket and tie.

Despite stakes so small you need a microscope to spot them, the commentariat couldn't let this pass. "Dress codes are a marker of social, national, professional or philosophical commonality," pronounced Southern Methodist University's Rhonda Garelick in The New York Times, in a lamentation titled "What We Lose When We Loosen Dress Codes." "A sea of 100 adults all dressed in some kind of instantly recognizable, respectful manner — a suit and tie, a skirt and jacket — creates a unified visual entity. A group in which individuals have agreed to subsume their differences into an overarching, sartorial whole." Yet even she had to admit that the Senate "has never been more divided" despite its longstanding informal dress code. Precisely how adding sweatpants into the mix was going to make things worse is unclear.

New York Post political reporter Jon Levine, who helpfully exposed the designer of Democratic New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's notorious "Tax the Rich" Met Gala gown as a tax cheat, tossed on Fetterman garb and tried to get seated at the Big Apple's finest eateries. He mostly got turned away, but the three-Michelin-star Eleven Madison Park, where a nine-course, vegetarian tasting menu costs $365, told him he'd be welcome. What this proves is unclear, even if it provides raw material for Twitter feuds and Halloween costumes.

The momentary suspension of the dress code roused to life the frustrated standups of the Senate, such as chucklemaster Susan Collins (R–Maine), who joked, "I plan to wear a bikini tomorrow to the Senate floor." On a more somber note, Sen. Roger Marshall (R–Kan.) told the A.P.: "I represent the people of Kansas, and much like when I get dressed up to go to a wedding, it's to honor the bride and groom, you go to a funeral you get dressed up to honor the family of the deceased." Marshall is hardly alone in invoking funerals when discussing the Senate, where the median age of members is 65.3 years, by some accounts the second-oldest cohort in history. The only question: Who exactly is the corpse in his scenario?

Maybe it's democracy itself. In 1974, Congress revised and updated its budget process into its current form, with the House and the Senate mandated to pass appropriations bills governing outlays for the coming fiscal year before it begins each October 1. You would think that authorizing federal outlays—however misguided they may be—would be the minimum accomplishment of any given Congress, the equivalent of just showing up for class. Yet since 1977, the first year that the new rules were in effect, Congress has managed to actually get its budget work completely done on time just four times—in fiscal 1977, 1989, 1995, and 1997. Instead, it half-asses everything for as long as it can and then relies on various types of resolutions to keep on spending until our elected leaders get around to letting us know how much we're on the hook for.

As the Pew Research Center notes, since fiscal 1997, "Congress has never passed more than five of its 12 regular appropriations bills on time. Usually, it's done considerably less than that: In 11 of the past 13 fiscal years, for instance, lawmakers have not passed a single spending bill by Oct. 1" (emphasis in original). That will almost certainly hold true for this fiscal 2024, alas.

The inability to get anything done helps to explain the history of government shutdowns, including the most recent—and longest—one, which started in December 2018 and carried over into the next year. Absent some probable last-minute deal making, the next one is due to start on Sunday.

Of course, shutdowns are far from the worst thing that can happen, especially given the massive and rampant waste in spending (most of which is on autopilot, coded as "mandatory spending" that doesn't need to be reauthorized each year). The hysteria that surrounds any minor hiccup in federal outlays is inevitably overwrought and ridiculous, but it is revealing nonetheless. It's good to know, for instance, that the Pentagon has unilaterally declared Ukraine aid sacrosanct. Sadly, the shutdowns don't actually prevent any spending from happening. They just push back its timing by a few days, weeks, or months.

More important, shutdowns borne out of congressional laziness are a sign that our leaders are fundamentally unserious, regardless of whether they dress flamboyantly like Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (I–Ariz.) or rock Carhartt hoodies like Fetterman. The "new, enforceable" dress code that was pushed through last night by Sens. Mitt Romney (R–Utah) and Joe Manchin (D–W.Va.) calls for business attire for men—"a coat, tie and slacks or other long pants." It's not exactly clear what it means for female senators, who caused a fuss by daring to wear pantsuits back in the 1990s. That passing a dress code will likely be among the greatest legislative achievements of Manchin and Romney (who is stepping down at the end of his current term) is a sad commentary on their Senate runs.

Judging by their record when it comes to the budget process, it's too much to expect that members of the "world's greatest deliberative body" will do their jobs, much less actually cut spending, reduce the size and scope of government, or even forego alleged bribes. But at least there is one less distraction when it comes to holding them accountable for record-high levels of debt.

Show Comments (98)