Welfare Cuts Are Inevitable Because Congress Won't Touch Social Security

Until Congress is willing to acknowledge that it makes no sense to send monthly checks to wealthy seniors, everything else will be on the chopping block.

Amid the fractious debate over the federal budget, Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy (R–Calif.) has outlined plans for cutting several prominent welfare programs in order to save about $150 billion annually.

According to The Washington Post, those cuts would affect a wide range of federal safety net programs including some—like food stamps and Meals on Wheels—that help feed needy families. Other cuts would affect Federal Pell Grants for low-income college students, grants that help families afford housing, and a program that helps offset high heating bills.

Regardless of whether you think the federal government should be in the business of funding any of those things in the first place, there's no denying the fact that sudden cuts to existing welfare programs can be disruptive to the individuals and families that have come to rely upon them. It's also true that, as Reason's Liz Wolfe points out in this morning's newsletter, the proposed cuts reflect the reality of a government that has been living beyond its means for too long. "It's not exactly a winning PR move to slash the programs that serve needy toddlers and first-generation college kids, but there's an important fundamental truth at the heart of the fiscal hawks' concerns: government spending simply cannot continue at current levels with no consequences," Wolfe writes.

That's true. But here's an element of this debate that doesn't get talked about enough: Cutting welfare programs for needy families is necessary because Congress insists that relatively wealthy senior citizens get paid first.

Budgeting is always, at its core, an exercise in priority-setting. That's especially true when your budget is wildly out of whack and you've been borrowing at an unsustainable rate, as Congress has done for years. When there's no longer enough money to go around, you're faced with a difficult proposition: Who gets paid first, and who has to wait at the back of the line?

In the federal budget, seniors get paid first. Everyone else has to wait.

McCarthy and his fellow Republicans are not proposing any cuts or changes to Social Security and Medicare, the Post notes. That's despite the fact that it's actually the two major entitlement programs that are driving most of the federal government's long-term deficit.

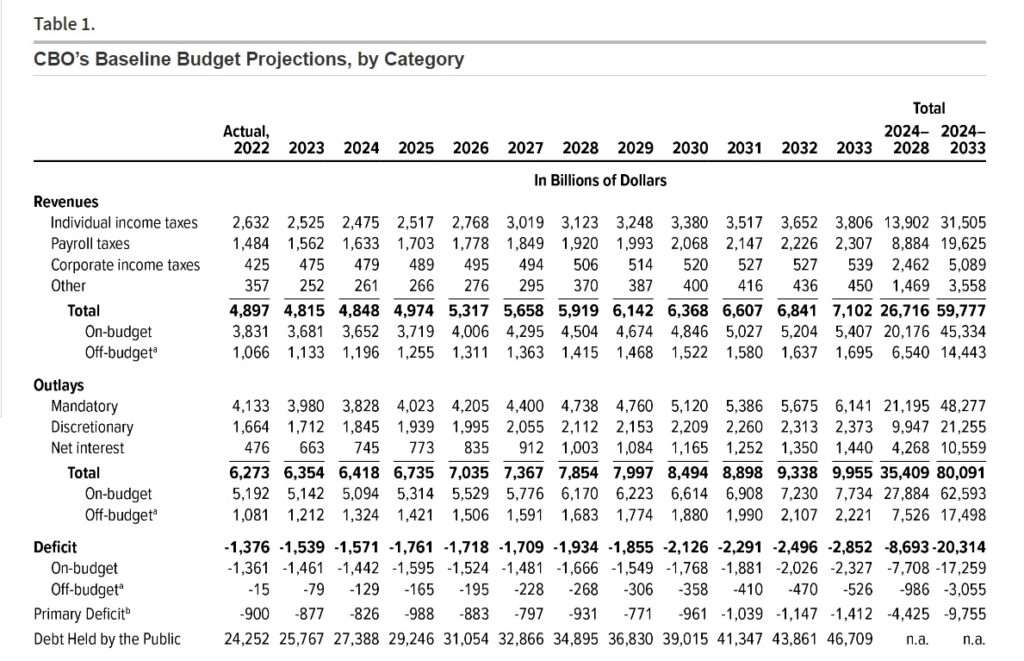

Over the next decade, discretionary spending—which includes those welfare programs the GOP is aiming to cut—is projected to decline relative to the size of the U.S. economy, according to the Congressional Budget Office's (CBO) projections. Meanwhile, Social Security and Medicare are growing, fast. By 2030, the CBO expects so-called "mandatory spending" on entitlement programs to consume more than 60 percent of the federal budget.

Of course, because those programs are funded with a separate revenue stream—payroll taxes—it would be complicated for Congress to cut spending on Social Security to offset cuts on welfare programs.

Even so, the ongoing refusal of either major party to consider any long-term changes to the two major entitlement programs tells you all you need to know about the priorities in Washington.

There is no shortage of alternative ideas out there. Congress could fiddle with the specifics of Social Security to make the program less expensive over the long term—raising the retirement age, for example, or changing how contributions and disbursements work. It could (and should) allow younger Americans to opt out of the system retirement.

It could means-test Social Security benefits to restrict payouts to wealthier retirees, in much the same way that welfare programs already do. That wouldn't save much money in the grand scheme of the federal budget, but it would reflect the economic reality that older Americans are generally wealthier. It makes little sense for the federal government to continue transferring cash from younger, working-age Americans to wealthy retirees—and it makes even less sense when there's a budget crunch.

Until some of these ideas are considered, however, the old-age entitlement programs will continue to be the primary drivers of the federal government's fiscal problems. As the entitlement programs grow more expensive over the next decade, they will continue to squeeze other parts of the federal budget. We'll be back in this same spot next year and the year after that—at least until the early 2030s, when Social Security will hit insolvency and more significant decisions will have to be made.

It is unlikely that any member of Congress will admit as much, but voting for a budget that cuts welfare programs while maintaining the status quo for Social Security and Medicare is a policy choice. It means that some struggling families won't get food stamps, but 70-year-olds with million-dollar nest eggs and vacation homes will keep getting monthly checks from the government.

Until those priorities change, everything else will be on the chopping block.

Show Comments (107)