The Vast Majority of People Who Want To Immigrate to the U.S. Have No Legal Option

A new Cato Institute report highlights just how hard it is to come to the U.S. legally.

Critics of illegal immigration often say that foreigners should simply wait in line and come to the U.S. the "right" way. But "fewer than 1 percent of people who want to move permanently to the United States can do so legally," according to a new report by David J. Bier, associate director of immigration studies at the Cato Institute.

"Legal immigration is less like waiting in line and more like winning the lottery," writes Bier. "It happens, but it is so rare that it is irrational to expect it in any individual case."

In a 2018 Gallup poll, 158 million adults interested in leaving their home countries said they most wanted to relocate to the U.S., the Cato analysis explains. (Even with a more liberal U.S. immigration system, George Mason University professor Ilya Somin correctly points out that some of those 158 million would likely be deterred by "moving costs" like learning a new language or landing a job.) "While it is not perfect," Bier says, the Gallup poll is "the best available estimate of the demand for green cards." He continues:

Meanwhile, administrative data indicate that roughly 32 million immigrants—adults and children—were attempting to become U.S. legal permanent residents in 2018, and the United States granted legal permanent residence to only about 1 million people….This means that about 80 percent of people wanting to immigrate to the United States could not even attempt the process, and about 99.4 percent did not yet qualify that year.

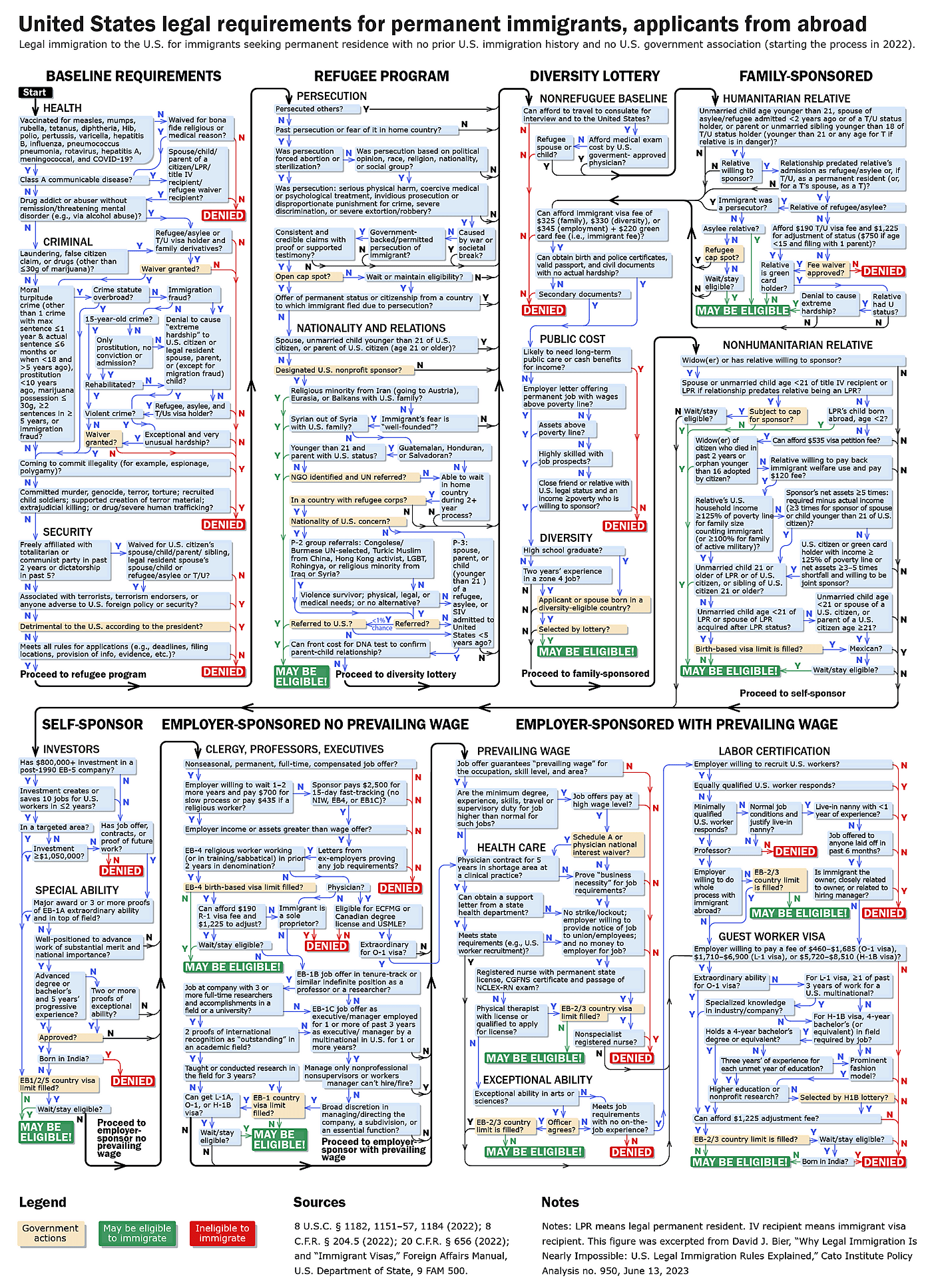

A foreigner who wants to secure a green card—which allows them to live and work in the U.S. indefinitely and later apply for citizenship—must qualify for one of five selective categories, says Bier. There's the refugee program, where "qualified refugees have less than a 0.1 percent chance of being selected for resettlement" and only some nationalities are eligible; the diversity lottery, where "applicants have a 0.2 percent chance of receiving a green card"; family sponsorship, which is capped for relatives beyond spouses, minor children, and parents; employment-based self-sponsorship, which requires high professional or financial standing; and employer sponsorship, a pathway so byzantine that very few employers actually use it.

Many factors keep foreigners from qualifying for those categories. Those include low annual visa caps, a lack of U.S.-based sponsors (whether employers or qualifying family members), narrow definitions of eligible nationalities, and cost. Some groups, including Indian nationals, can face decadeslong or lifelong waits for green cards—even if they're already in the U.S. on renewable work visas.

Today's legal immigration system is drastically different than what it was historically. Post-independence, the U.S. took a broadly liberal approach to welcoming newcomers. "Even when it finally adopted some rules in the late 19th century, immigrants were presumed eligible for permanent residence unless the government showed that they fell into specific and usually narrow ineligible categories," writes Bier.

Now, would-be migrants have to prove their eligibility based on strict prerequisites that vanishingly few can fulfill. That shift hasn't reduced demand for migration pathways—it's just created a black market, much like other forms of prohibition. Rather than looking to a sensible, straightforward, and sanctioned visa application process, migrants of many stripes look to smugglers and illegal entry to reach American soil. This has made their journeys far more dangerous (and, in many cases, deadly).

Bier suggests some reforms to help American employers and would-be foreign workers and reduce illegal immigration. One is the creation of "a streamlined work visa program for year-round, lesser-skilled workers." Another is the repeal of "overall and country-based employer-sponsored caps" for visas, which can lead to unfathomable wait times, barring workers from bringing their skills to the U.S. economy.

Liberalizing the immigration system would be a boon to both migrants and native-born Americans, to say nothing of the huge benefits that would come from new Americans starting businesses, filling critical jobs, and contributing to their local communities.

Show Comments (285)