Supreme Court Reins in EPA Overreach

Thanks to Sackett v. EPA, the feds can no longer treat a backyard puddle like it's a lake.

The U.S. Supreme Court in a 5–4 decision reined in the Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) effort to impose extensive federal land use regulation through its broad interpretation of the Clean Water Act (CWA). The decision in the case of Sackett v. EPA turns on the question of the proper definition of the term "the waters of the United States" (WOTUS). Interestingly, all the justices concurred in the judgment that plaintiffs Michael and Chantell Sackett's property and actions were not covered by the CWA.

In the case, the Sacketts had purchased property near Priest Lake, Idaho, and began backfilling the lot with dirt to prepare for building a home. The EPA claimed that the property contained wetlands over which the agency exercised authority under the Clean Water Act which prohibits discharging pollutants into "the waters of the United States." The EPA threatened to impose a fine of $40,000 per day if the Sacketts did not desist.

The majority opinion written by Justice Samuel Alito noted that EPA bureaucrats had "classified the wetlands on the Sacketts' lot as 'waters of the United States' because they were near a ditch that fed into a creek, which fed into Priest Lake, a navigable, intrastate lake." The EPA's ruling against the Sacketts was upheld in federal district court and the 9th Circuit Appeals Court.

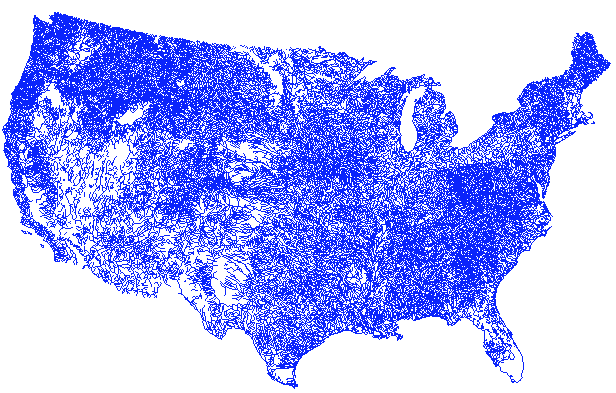

The majority decision reaches the commonsense conclusion that waters of the United States refer to what in ordinary parlance are streams, oceans, rivers, and lakes and includes adjacent wetlands with a "continuous surface connection" to such waterways. Under the "significant nexus" test developed by Justice Anthony Kennedy in the 2006 decision Rapanos v. United States, nearly any body of water, no matter how isolated or impermanent, can be defined by the EPA as being part of the waters of the United States and are therefore subject to federal regulation under the Clean Water Act. "By the EPA's own admission, nearly all waters and wetlands are potentially susceptible to regulation under this test, putting a staggering array of landowners at risk of criminal prosecution for such mundane activities as moving dirt," observes the court in its syllabus of the case.

The syllabus argues that the CWA applies to adjacent wetlands when those wetlands are "indistinguishable" from other properly regulated bodies of water. Adjacent wetlands are covered by the CWA when they have "a continuous surface connection to bodies that are 'waters of the United States' in their own right, so that there is no clear demarcation between 'waters' and wetlands."

In his concurring opinion joined by three other justices, Justice Brett Kavanaugh observes that the majority decision "invokes federalism and vagueness concerns. The Court suggests that ambiguities or vagueness in federal statutes regulating private property should be construed in favor of the property owner, particularly given that States have traditionally regulated private property rights."

As Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in his concurring opinion, "The Court's opinion today curbs a serious expansion of federal authority that has simultaneously degraded States' authority and diverted the Federal Government from its important role as guarantor of the Nation's great commercial water highways into something resembling 'a local zoning board.'"

Kavanaugh then counters that the "Federal Government has long regulated the waters of the United States, including adjacent wetlands." Well, yes. But the question is whether the Clean Water Act actually confers that regulatory authority. In arguing that it does, Kavanaugh argues that the CWA refers to "adjacent" wetlands which would include those that do not have a continuous surface connection to navigable waterways. Therefore, the Court's majority decision inappropriately narrowed the definition of "adjacent" with respect to the EPA's jurisdiction over wetlands.

I am definitely not a legal scholar, but the majority of the Court is entirely right when it points out that the "system of 'vague' rules" devised under the EPA's expansive interpretation of the CWA left landowners subject to uncertain and capricious enforcement. This decision should now provide landowners more legal certainty and security as they formulate their plans with respect to how they want to manage and care for their property.

Show Comments (52)