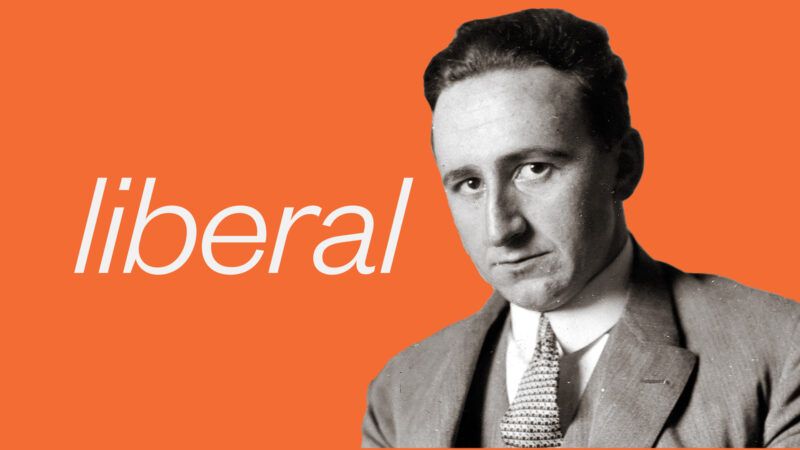

Hayek Was a True Liberal

A new biography tells the story of the economist’s early life and career.

Too many on the left think of the Nobel Prize-winning economist Friedrich Hayek as "conservative," or at best "neoliberal." But Hayek was no conservative. He was a liberal, no "neo" about it. A new biography, Hayek: A Life, by the historians of economic thought Bruce Caldwell and Hansjörg Klausinger, tells the story of his first five decades in 824 pages of mind-stunning detail.

Hayek was a leader in the third generation of the so-called Austrian School of economics. Worldwide now, though a minority view, it did originate in Austria. Starting in the 1870s, the founder Carl Menger developed and defended a radical improvement in the English liberal economics of Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and J.S. Mill.

The opponents of liberalism in Menger's time were devotees of an echt German "historical school," which admired the coercive masters of old and recommended new ones. In the U.S., opponents of liberal Austrian economics were called institutionalists—they sought to impose institutions, whether you like it or not. So too nowadays do neo-institutionalists such as Douglass North and Barry Weingast and Daron Acemoglu.

The Austrian School of Menger, Ludwig von Mises, Hayek, Israel Kirzner, Murray Rothbard, and now Peter Boettke recommends instead that we stick with pretty good spontaneous orders. They arise all over the place from masterless people interacting as they do in, say, the English language, German music, American Wikipedia, Dutch friendship, French cuisine, and the world economy. Except in totalitarian countries like the one Xi Jinping fantasizes about, most of life occurs outside the state. How often, after all, do you enforce a contract in the state's courts?

So Hayek and the Austrian School are liberal, in a modern world lurching between the fatal conceits of left and right. On the left nowadays Acemoglu and James Robinson, and more radically Thomas Piketty and Mariana Mazzucato, recommend a bigger and bigger state. They promise it will be a very nice one, you understand. On the right Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin recommend a bigger and bigger state. They make no such promises about niceness. They envision a state of the sort that Hayek opposed in Russia and then in the German lands, growing up with Viennese antisemitic politics and the street violence of Weimar Germany next door. We liberals stand apart from the usual spectrum, recommending as Hayek did a competent but small state, liberty with love.

The peculiarly American term for such a worldview is libertarianism. The usage delivers liberal over to the social democrats. Hayek and I disapprove. True liberalism adopts instead the strange and wonderful idea arising suddenly by happy accident in northwestern Europe during the 18th century that the ancient hierarchies of husband and master and king should not stand. Ordinary people were to be treated for the first time like adults. Such a liberalism could be called adultism.

In their biographical volume, which covers 1899–1950, Caldwell and Klausinger tell everything about Hayek's youth you wanted to know but were afraid to ask. From his happy childhood in Vienna and foolhardy service as a junior officer in the Austrian army on the Italian front, he went during the 1920s to university and then a research job with Mises. He shifted in his commitments from a sentimental socialism to an intellectual liberalism. So did numerous leftish intellectuals during the 20th century—Leszek Kołakowski, Robert Nozick, Thomas Sowell. I did too, though not as rapidly as Hayek did. The old joke is that if you are not a socialist at age 16, you have no heart. If you are still a socialist at age 26, you have no brain.

Hayek was partly converted as early as age 23 by Mises' 1922 book Die Gemeinwirtschaft (Collectivized Economy; published in English in 1936 as Socialism). "I had already grown very skeptical [of central planning]," he wrote, perhaps from watching the Austrians and the Italians do utterly incompetently what states are primarily formed to do, waging bloody war. Some in my generation drew the same lesson from the blood of Vietnam. Yet, like me and many others, Hayek could not for a long time fully embrace what he already knew: "I would not have said then—as I do now—that socialism is not even half right, but totally wrong."

My own conversion book was Nozick's 1974 Anarchy, State and Utopia. Back in college a dozen years earlier my roommate Derek and I, majors in the Keynesian economics on offer then, sneered loftily at our electrical engineer roommate David for reading Mises' 1949 Human Action. David, relaxing from solving second-order differential equations, would light up an unfiltered Gauloises cigarette, lean back in his office chair, and perch the old Yale Press edition on his knees. If I had not sneered but read, I would have saved at least a dozen years—more like the 30 or so it took me to grasp much of the Austrian contributions to economics, especially in its theory of markets and discovery.

Caldwell and Klausinger move through Hayek's unhappy first marriage, his rejection of Viennese antisemitism, his teaching at the London School of Economics in its creative decade of the 1930s, and his composing in the 1940s The Road to Serfdom. In April 1945, that work was condensed in a famous issue of Reader's Digest for 5 million subscribers and given free to millions of soldiers. In the harsh pro-socialist climate of the time among the intelligentsia, the book ruined Hayek's then-lofty reputation as an academic.

In 1947, he led the first Mont Pelerin meeting of the handful of anti-socialist liberals, at the high point of world socialism. Hayek served as the president of this alarming discussion group of professors from 1947 to 1961, as he turned from technical economics to political philosophy, where he at length rebuilt his reputation—but those developments await the reader in Volume 2.

That volume, to be co-authored by Klausinger and the brilliant Bulgarian-German Stefan Kolev, will have to find its way through conflicting accounts of Hayek's controversial statements on Chile and his interactions with Augusto Pinochet. (Yet the Chicago Boys, so often unfairly tarred with the sins of that Chilean strongman, were mainly taught price theory at the University of Chicago by a liberal named, uh, McCloskey.) That volume will tell of his The Constitution of Liberty (1960), his depression when he realized that few were listening, and his rise to world prominence after the Nobel Committee smiled. The Committee likes to pair opposite candidates, in a characteristically nonfunny Swedish joke. So it awarded the glittering prize in the same year to Hayek and to the Swedish socialist Gunnar Myrdal.

In 1960, Hayek wrote a persuasive appendix to his own big tome, The Constitution of Liberty, explaining "Why I Am Not a Conservative." (That didn't stop the conservative National Review from ranking it ninth among the 100 best books of the century.) Hayek noted that the political right wants to coerce us to construct a fantastic version of a lovely past and the left wants to coerce us to construct a fantastic version of a future heaven. We liberals do not want to coerce anyone. And we don't like fantasies.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Google pay 200$ per hour my last pay check was $8500 working 1o hours a week online. My younger brother friend has been averaging 12000 for months now and he works about 22 hours a week. I cant believe how easy it was once I tried it outit..

🙂 AND GOOD LUCK.:)

HERE====)> http://WWW.WORKSFUL.COM

I get paid over 190$ per hour working from home with 2 kids at home. I never thought I'd be able to do it but my best friend earns over 10k a month doing this and she convinced me to try. The potential with this is endless. Heres what I've been doing..

AND GOOD LUCK.CLICK HERE...............>>> onlinecareer1

I get paid over 190$ per hour working from home with 2 kids at home. I never thought I’d be able to do it but my best friend earns over 10k a month doing this and she convinced me to try. The potential with this is endless. Heres what I’ve been doing..

HERE====)> http://WWW.RICHSALARIES.COM

Great article, Mike. I appreciate your work, I’m now creating over $35000 dollars each month simply by (gbf-52) doing a simple job online! I do know You currently making a lot of greenbacks online from $28000 dollars, its simple online operating jobs.

Just open the link———————————————>>> http://Www.RichApp1.Com

I am making $92 an hour working from home. I never imagined that it was honest to goodness yet my closest companion is earning $16,000 a month by working on a laptop, that was truly astounding for me,

she prescribed for me to attempt it simply. Everybody must try this job now by just using this website. http://www.LiveJob247.com

"We liberals stand apart from the usual spectrum, recommending as Hayek did a competent but small state, liberty with love."

Love? No thanks.

Love implies caring, and caring motivates (and justifies) interference with specific intent.

How about a small, disinterested state?

"Love" is one of those chameleon words which means whatever the user wants it to mean, and sows confusion in all recipients. We love pizza, our dog and truck and its bumper stickers, special songs, our children be they criminals or geniuses ... loving a sunset does not involve any caring which can turn to coercion. Think of "liberty with love" as "enjoyment" or "appreciation". There are plenty of non-coercive words which will do.

We love pizza, our dog and truck and its bumper stickers, special songs, our children be they criminals or geniuses … loving a sunset does not involve any caring which can turn to coercion. Think of “liberty with love” as “enjoyment” or “appreciation”. There are plenty of non-coercive words which will do.

Well, don’t let Rev. Artie hear any of this Tom T. Hall stuff or he’ll accuse you of being a slack-jawed, country-come-to-town, can’t-keep-up, clinger!

🙂

But if Rev. Artie does show up, play this to him and make him puke! 🙂

I Love--Tom T. Hall

https://youtu.be/65AuuFpNFxY

My last month's online job to earn extra dollars every month just by doing work for maximum 2 to 3 hrs a day. I have. joined this job about 3 months ago and in my first month i have made $12k+ easily without any special online experience. Everybody on this earth can get this job today and start making cash online by just follow details on this website.OPEN>> ONLY USA JOBS

How about a state so small you can stuff it in a shoebox and launch it into the sun?

I want one big enough to pile all the leftists onto it.

Love means letting go. You love your child so you let them grow up and leave. Love is not controlling. Love is not stifling.

Government is not a person, however, and can't love. Only individuals can love. But liberalism (the real liberalism, not that progressive shit that took over the word) is individualist, and individuals love.

On the right Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin recommend a bigger and bigger state. They make no such promises about niceness.

Conservatives need a bigger and bigger state to implement their authoritarian vision of society.

Good essay. Of course as a Hayek liberal I am showing my bias. Hayek would no doubt despise Trumpian policies.

A few years back you posted kiddy porn to this site, and your initial handle was banned. The link below details all the evidence surrounding that ban. A decent person would honor that ban and stay away from Reason. Instead you keep showing up, acting as if all people should just be ok with a kiddy-porn-posting asshole hanging around. Since I cannot get you to stay away, the only thing I can do is post this boilerplate.

https://reason.com/2022/08/06/biden-comforts-the-comfortable/?comments=true#comment-9635836

Don't respond to SPB, just shun him.

“A decent person would….”

…….have no interest at all in finding or posting cp. Can’t get back to “decent” from there just by honoring a ban.

Might I suggest a slight edit to your boilerplate?

It would also be helpful if said boilerplate included the promised "all the evidence". As provided, it proves absolutely nothing and, indeed raises interesting questions about how our valiant anti-SPB--er, anti-CP--sleuths managed to determine the allegedly illegal nature of the alleged linked content without themselves ever downloading it.

Ideally I would prefer Shrike to be no longer alive.

Google pay 200$ per hour my last pay check was $8500 working 1o hours a week online. My younger brother friend has been averaging 12000 for months now and he works about 22 hours a week. I cant believe how easy it was once I tried it outit..???? AND GOOD LUCK.:)

HERE====)>>> GOOGLE WORK

You are not a Hayekian liberal, just another progressive pretending to be a libertarian.

Not seeing it. Buttplug says some stuff I disagree with, but it's all within the libertarian spectrum.

The people who like to accuse others of gaslighting are fond of telling people they are wrong when they say what they think, and then telling them what they really think.

I’ve noticed.

Yeah, you fags are big fans of the pedophile. Goddamn Sarc, this doesn’t help you. Just clear out and show some fucking grace for once.

Conservatives need a bigger and bigger state to implement their authoritarian vision of society.

Now do democrat socialists.

The difference between the political left and the political right at this point is not control versus liberty. Nope. Except for guns, the right doesn’t give a whit about liberty. The differences are only over what they want to control and who they want to control it. Liberty isn’t even on the radar.

Pretty much this.

Conservatives are not natural libertarians, as Hayek noted. They prefer order and hewing to tradition. Conservatives are the more libertarian party in the USA because the Founders were decidedly libertarian, and founded the government on libertarian principles.

But liberals have no allegiance to the past, and will embrace change if it might improve the human condition. Unfortunately they are beyond gullible and immune to evidence when spending more doesn’t work (or pretty much when any government policy or mandate doesn't work as intended), and easy marks for those who want to accumulate power and enrich their allies.

That’s why liberals aren’t liberal anymore. They’ve been consumed by the cancer that is Marxism and are no hollow, soulless, wokie husks.

When exactly were US "liberals" ever liberal?

Why bother? Both halves of The Entrenched Looter Kleptocracy are identical in all but ignorant violence, which Grabbers Of Pussy have down pat. All improvement this past half-century, such as the Roe v Wade decision and weakening of shoot-first prohibitionism, has been copied from LP platforms thanks to spoiler votes.

Roe v Wade is not part of the LP platform, and if it was unconstitutional, it's not an improvement.

RvW was unconstitutional. It was judicial activism is the truest sense. The ruling, written by the court not the legislature, became law. It was legislating from the bench. So overturning it was a good thing. If the Democrats had been on the ball when they had majorities and the White House, they could have codified the ruling into legislation and it would have stuck. But because it was a court ruling, not something passed by the legislature and signed by the president, it was overturned.

Edit: Democrats had fifty years to turn that ruling into law. But they didn't. They've got nothing to cry about.

Change it into law? And lose all those fundraising dollars?? For all their talk, the last thing the Dems want is abortion codified at the federal level.

The overturning of RvW is a double bonus for Democrats.

People who think illegal abortion is the end of the world are voting in droves, and people who think legal abortion is the end of the world are staying home.

Hank loves infanticide as much as Shrike loves raping children or Sarc likes getting blackout drunk.

Hank loves infanticide more than almost anything.

Whereas the Democrats spend more than any previous government in recorded human history only to help the truly needy and to build a society we can all take pride in?

I get paid over 190$ per hour working from home with 2 kids at home. I never thought I'd be able to do it but my best friend earns over 10k a month doing this and she convinced me to try. The potential with this is endless. Heres what I've been doing..

AND GOOD LUCK.CLICK HERE...............>>> onlinecareer1

Trump is not 'on the right' or conservative in any traditionally accurate description.

He was able to get the right to make a hard left turn on economics.

Sure he did.

I am old enough to remember when protectionism and closed borders were things of the Left, policies arising from the quasi-Marxist trade unions that the Democrats were championing. The Right wanted Free Enterprise, the more radical on the Right openly used terms like Laissez Faire. A welcome of legal immigrants and an clear pathway to citizenship. The Right used to praise new citizens. Used to promote free trade. It was the Left that wanted endless tariffs and trade controls and closed borders and union membership for all God fearing White men.

Not conservative in the reactionary sense as the Left defines it, but conservative in the Burkean sense (himself a classic liberal). If not for the destructive influences of the Cold War that drove them to distraction, the American Right could well have been small L libertarian.

I read "Why I'm Not a Conservative" to mean that they didn't ever want to progress but were just a ball and chain attempting to slow the left and Hayek wanted to progress in a different direction than the left, towards liberty. Not that the right "wanted a big coercive state".

G. K. Chesterton said "The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of Conservatives is to prevent mistakes from being corrected."

Each recognizes the other is wrong, but refuses to recognize both are wrong.

Yes, this. And Hayek saw liberals as more willing to embrace change, and potentially more receptive to radical libertarian ideas than conservatives, who hew to the past.

Hayek also said the highest priority for libertarians should be abolishing the entitlement state. If the government is in charge of your retirement and your health care (Social Security and Medicare), people will grow dependent on the government and learn to love spending.

The whole point of Socialist Security was to make sure the impoverished elderly who were too proud to accept charity or a government handout, and would rather starve, freeze, and dogfood themselves to death, could cash a check from the government that they had "paid into".

And it worked. Now no one is too proud to cash stimulus checks and clamor for more.

The only way to keep the great majority of people interested in keeping the government small is to not send checks to the great majority of the people.

Hayek wasn't opposed to welfare or medical care (Medicaid) to the truly needy. Now conservatives oppose both of those safety net programs and stare down anyone who won't "keep your hands of my Social Security and Medicare!"

Well that book certainly looks like a too long for me to read book. But volume 2 might be better if it includes a lot of why and how he changed emphasis towards the neural science stuff

If Hayek were alive he'd have been a very vocal critic of Trump, and as a result most of the people in these comments would be calling him a progressive.

Because tiny minds who see politics as left or right interpret any criticism or disagreement with their team as support for the other team.

It's really sad. Very sad. So sad it almost makes me sad.

Nah. You’re just an angry drunk that is as obsessed with hating Trump as you are getting blackout drunk.

So besides crib from Adam Smith, Frédèric Bastiat, HL Mencken and Lysander Spooner, what has this latest Anschluss transportee from Germany's AfD actually done? Rothbard, von Mises and even Milton Friedman failed miserably when it came to explaining the various Crashes and Depressions. Even Hitler was able to disagree with his fellow socialists and make predictions just as wrong--big, fat, hairy deal. What successful predictions has Hayek chalked up?

"What successful predictions has Hayek chalked up?"

Describing markets as a product of human action, not human design, is kind of like saying predictions are useless.

Rothbard failed to explain why the Federal Reserve, an entity founded to "smooth out the business cycle", instead made recessions and depressions far worse? I think he explained it a lot better than some current Nobel Prize Winning Economist could.

IIRC, Rothbard thought Hayek was a sellout.

Rothbard's disapproval would be something to wear with pride.

Just like yours.

I cannot now remember which I read first - "The Moon is a Harsh Mistress" or "Atlas Shrugged" - but they were both responsible at about the same time for my conversion from socialism to liberty. Most people do not read economic books for entertainment, so unless you are an economist or economics student, you are most likely to flirt with libertarianism for the first time because of sci-fi. I think I read "Economics in One Lesson" before I read Hayek, and I'm pretty sure that I watched "Free to Choose" on PBS long before it became available on DVD.

Heck, I had Free To Choose on VHS.

Yeah, but with VHS, you weren't Free To Choose Betamax or Laser Disc! 😉

It was NOT Ayn Rand for me. Nope, not atheism, it was the Christian Anti-Communist Crusade newsletters my mom subscribed to. Rather than shout "godless" like most anti-communist groups, it actually took the time to explain the basics of economics and why communism and central planning didn't work. It explained individualism and collectivism. In retrospective, it was very much influenced by Mises and Hayek.

Also, at the time the local, state, and national farm bureaus and chamber of commerces were quite free market and free enterprise. So I was primed. All I needed was a pamphlet from the LP and I was sold. Drugs and prostitution? Moral sins to be sure, but it was not the business of government to police morality.

I despise that phrase "If you not a socialist when you're 16..." There is no excuse, either at 16 or 26, for advocating a system that killed 100 million people, at least half of whom were killed before the author was born.

Blaming it on a youthful heart is bullshit. Just apologize for it, preferably to the families of those who were murdered by socialist regimes. Then "Go and sin no more".

Former socialists almost always have a socialist residue that keeps them from acknowledging individual rights. Hayek rejected the idea of inherent rights. His defense of the free market is peppered with a kind of proto post-modern epistemology of ignorance.

It is not ignorance or conceit that make it impossible to run an economy from the top. It's the fact that humans possess free will and create things that cannot be known in advance because they can only be known once they exist. Individual rights, in particular property rights, are the recognition that human beings exist by virtue of their capacity to create the things they need.