Why Are Half of All U.S. Exonerations of Black Prisoners?

A new report looks at decades of troubling trends of bad convictions in murder, rape, and drug cases.

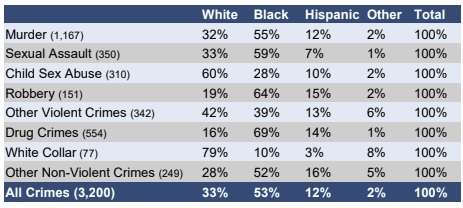

Black people represent less than 15 percent of the U.S. population, but they account for more than half of all exonerations, according to a new report released today.

The National Registry of Exonerations releases an annual report each spring documenting trends in cases the previous year where people who have been convicted of crimes have subsequently been found guilty. Today's report delves into racial patterns of the 3,200 exonerations the registry has documented dating back to 1989.

The registry has taken note in its past annual reports of how black citizens are much more likely to be falsely convicted and then exonerated than white defendants. This report, looking over decades of history, shows that innocent black Americans are seven times more likely than white Americans to be falsely convicted.

There are some categories, like child sexual abuse and white-collar crimes, where a greater percentage of the exonerations are of white defendants. But in all categories except for white-collar crimes, blacks are disproportionately represented compared to their share of the population.

The reasons why are varied depending on the crime. It's more complicated than simply crying "racism," and the report explores some of the systemic issues. When talking about murder, the report doesn't shy away from the high homicide rate within the black community and the fact that the vast majority of homicides among both whites and blacks target somebody of the same race. Nevertheless, you can see big disparities in the likelihood of a black person getting convicted for a murder in which they are innocent. The report calculates that even though 40 percent of defendants imprisoned for murder are black, 55 percent of those exonerated for murder are black.

We shouldn't take this to mean that we should be looking for a more representative balance of race among exonerees. Rather, it's a warning of how our justice systems handle or mishandle investigations or prosecutions when the defendants are black. The report notes, "Official misconduct is more common in murder convictions that lead to exonerations of black defendants than in those with white defendants." The report analyzes several different types of government misconduct—from concealing evidence to witness tampering to perjury by officials—and calculates that such misconduct can be found in a greater percentage of murder cases with black defendants than white defendants. The difference is just 14 percentage points, but when you account for the greater number of black exonerations, official misconduct played a role in twice as many convictions (500 blacks to 236 whites) documented in the registry. And the study attributes the difference in the rate almost entirely to police misconduct.

For sexual assault, nearly 60 percent of all rape exonerations were of black defendants, even though only a quarter of all rape prosecutions involve a black defendant. Most are the result of misidentification by rape victims, most of whom were white. Innocent black people are almost eight times more likely to be falsely convicted of rape.

The misidentification problem is well-established by now, and the report points to the simplest explanation: "One of the oldest and most consistent findings of systematic studies of eyewitness identification is that white Americans are much more likely to mistake one Black person for another than to mistakenly identify members of their own race."

The number of new exonerations for sexual assault has declined, and that's actually good news. The number has plunged because the availability of pretrial DNA testing has made it much less likely that somebody will be convicted due to misidentification. DNA-based exonerations jumped up through the 1990s and early 2000s and then started to decline as the availability of testing stopped innocent people from being convicted in the first place. There have been only two documented cases of misidentified rape victims being exonerated since 2009.

Drug crime convictions also get some heavy analysis here because of the disproportionate enforcement of drug laws and the corruption it fosters in black communities. Even though surveys from the Department of Health and Human Services show that white and black people use drugs at similar rates (12 percent and 13.7 percent, respectively), blacks are up to five times more likely to be arrested for drug crimes, depending on the year surveyed.

The report notes that there's very little effort to exonerate people convicted of low-level crimes, even if they are innocent. Much of the effort focuses on people with very long prison sentences instead. But drug crimes are a big exception. They account for 17 percent of all exonerations, the second largest category after murders.

The registry focuses on these types of exonerations because of how they illuminate some very serious trends in bad policing. The registry notes clusters and groups of exonerations due to bad policing practices that draw in dozens, possibly even hundreds, of false convictions. In Harris County, Texas, for example, 157 exonerations happened over several years of people who had pleaded guilty to drug possession. Subsequent testing uncovered no illegal drugs in the substances that had been seized. And the registry notes that these exonerations only happened because Harris County has a policy of testing the drugs in a laboratory even if the suspect pleads guilty.

In Chicago, 186 people have been exonerated of drug crimes since 2017 due to a pack of police officers planting drugs, falsifying records, and committing perjury as part of running their own drug racket.

The emphasis on race when discussing criminal justice can frustrate people who see it all as a polarizing part of the culture war. The report doesn't treat it that way, fortunately. But what it does note in its conclusion is something libertarian criminal justice reformers note all the time. The elimination of the drug war entirely would result in a more just system that would be less likely to result in minorities as targets for police abuse. The solution to some of this racist police behavior isn't training or empathy or lectures on critical race theory. It's to just end the stupid drug war. The report concludes:

The causes of this extreme racial discrepancy are plain. Black people are much more likely than white people to be stopped and searched by officers who are trolling for drugs, which puts them at risk of false drug convictions based on factual errors. And Black people are the great majority of the victims of police officers who systematically fabricate evidence to frame innocent defendants for drug crimes.

The solution is equally clear: Stop treating illicit drug use primarily as a criminal problem. The War on Drugs is a heavy burden on our country, but the worst costs are born by Black people and other people of color. If white people were stopped, searched and humiliated as often as Black people, would we even have a War on Drugs? What if police across the country engaged in methodical programs of planting drugs on innocent white people? It's hard to believe.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"Black people represent less than 15 percent of the U.S. population, but they account for more than half of all exonerations, according to a new report released today."

Clear and irrefutable evidence of racism in the exoneration program.

Lock up enough of them again to get the percentage back to 15.

They compare overall population, which isn't the right metric. It should be what percentage of prisoners, arrests and convictions. If the arrest population is 50% black, then 50% exoneration would only follow. Another thing to take into account is that many crimes are still convicted on witness statements, however, we know that there is a definite problem with obtaining witness statements or getting witnesses to agree (or even victims) to testify in certain communities. Often these communities tend to be minority communities, ergo, it has extremely hard to tease out causality in this case. It isn't necessarily evidence of any racism.

There's no way to slice it so that it makes sense, because any kind of comparing statistics ultimately leads to nonsense. The lazy part is measuring any two things, insisting as a matter of dogma that they should (in a just and fair world) be equal and then concluding, without any further research, that the reason they are different must be racism. It's simply meaningless noise. Observe:

Suppose blacks were 90% of exonerations, 50% of the prison population, and 15% of the population. What does that mean? It could mean that blacks are falsely convicted a lot of the time (if the number of exonerations is a substantial ratio of convictions). It could also mean that non-blacks are essentially unable to be exonerated (if the number of non-black exonerations is very low compared to the number of non-black convictions). If there were ten billion people in prison and only ten of them got exonerated it could just be statistically irrelevant. It could mean that blacks are more likely to pursue exonerations while non-blacks prefer to sit in prison quietly (e.g. if they took a plea deal).

It is utter rubbish.

"The registry has taken note in its past annual reports of how black citizens are much more likely to be falsely convicted and then exonerated than white defendants"

Can they actually infer that from the available data?

Obviously they can see the trend in exonerations but if that is their only measure of being falsely accused then it is a flawed metric and the statement becomes a narrative rather than a finding.

The article's trying awful hard to stitch a narrative together. It notes that 60% of sexual assault accusations are misindentifications, but the explanation is that wypipo confused one black man for another. Meaning any racial disparity is irrelevant and it's an economic argument. We're wasting money prosecuting the wrong black people and letting the wrong ones go free. Once Wypipo get better at identifying black people (visually or through DNA testing, which Reason also doesn't like), the 60% goes down and we lock more of them up for sexual assault.

Not only that but there is a hell of a lot of statistical abuse going on. Population overall instead of inmate population to infer the exonerations are out of line, prosecutions not convictions (which aligns with victim reports by race) to claim rape prosecutions are racially motivated. It's just a shitty proggy propaganda piece just like I've come to expect from the pedo defending "criminal justice" crowd of Reason writers actively cheering political prosecutions but ignoring the failures of every Soros DA initiative.

Not to take from the issue of white folks thinking that black folks look alike in a pinch, but, the same applies to other racial groups' perceptions of blacks, whites, Asians, Latinos. The facts are, witnesses are notoriously unreliable when it comes to visual identification, and every group is to some degree xenophobic. This canard that shackford trots out is ignorant at best.

I picked up on this as well. The article was working very hard to make a case for systemic/endemic racism. They touched on some confounders but you can tell they really wanted this to be about "white people are racist, the system is racist".

Need I remind you that Reason is run by progressives claiming to be libertarian?

Additionally, we have to take into account that finding exonerating evidence is largely a matter of luck, especially with murder, so you have to widen the error margins quite a bit.

40% of murder convictions are black. 55% of exonerations are black. That's fairly close and with a relatively small sample size. It might indicate only a very few bad actors or even random chance.

It means blacks are OVER represented in exonerations, and therefore more non-blacks need exonerated. That's how disparate impact works, right?

There is a matter of backlogs. Even after he was shot full of holes, Democrats overwhelmingly favored George Wallace if the Hero of Chappaquiddick couldn't be repackaged and sold. Bobby had earlier been riddled with bullets. So with southern rednecks of both looter persuasions packing prisons with nonviolent nonwhites, pressure from the LP is reversing that process and releasing persecuted minorities now looks like favoritism. (https://bit.ly/3Cg0cEU)

It doesn't work that way in the eyes of some people.

Several years ago a City Councilwoman in Pittsburgh complained that 80% of the people arrested in her District were Black. When it was pointed out to her that over 90% of the people in her District WERE Black, she said "I don't care. Arrest more White people."

Funny thing was that about six months later she was arrested.

Yup, the only absolute number given is the ‘problematic’ one, it’s lying with statistics. It’s not good that we’re exonerating thousands of people, but the homicide rate has hovered around 6 per 100K for the same 3 decades. Meaning around 600,000 homicides, and that if all 3000 exonerations were for homicides, we’re talking less than 0.5% of convictions.

Edit: And that's assuming the manner in which the exonerations were collected was a perfectly representative sampling.

It's also a matter of how much is invested in post-conviction exoneration efforts and sometimes the political optics.

So, my question is, is anyone who was responsible for the wrongful prosecution that resulted in a person (of any race) being incarcerated (police, investigators,witnesses, prosecutors, judges) ever held to account?

Many of the cops are given the dreaded two weeks paid vacation, while judges and prosecutors are slapped with the much harsher sternly-worded letter.

It's aggregate statistics that roughly correlate with the underlying conviction statistics. What are you going to convict them of, 'marginally above average misidentification'? Set a quota of misidentified black sexual assaulters every year and once that number is reached no more white women can accuse black men of sexual assault?

My guess is that the only way that will happen is if progressives can use it as a cudgel against conservative judges. And they can create an equity based climate of fear that sentencing any minority offender could possibly lose you your job or freedom.

It’s info I wish could be collated by lawyer and judge so that, come election time, you can see who prosecuted or tried exonerated cases.

No. Essentially, juries are blamed - the jury convicted, it's all the jury's responsibility. Even when actual criminal actions are discovered it's 'old news' and no one want to go through the effort.

Typical prosecutor: "It's the jury's fault they believed my lies!"

Only 50% of black prisoners have been released? Equity demands that we release 150%!

Black people represent less than 15 percent of the U.S. population, but they account for more than half of all exonerations, according to a new report released today.

Exonerations are pulled from the population who have been convicted, not the US population.

When you start a rant with bullshit like this people stop listening.

Amen.

However, people with a racial agenda smile and beat their chests, especially with an election that will "literally determine whether Democracy survives" is pending.

Skin color is the most important thing

A color blind society is a racist society...

And Democracy means the minority rules over the majority.

Freedom is Slavery after all.

Absolutely. Other media love talking about disproportionate (fill in the blank) but then use the wrong statistics to try and support their social justice based claim.

Black people represent less than 15 percent of the U.S. population, but they account for nearly half (48.9%) of all homicides, according to FBI statistics.

Don't toss out the first one without the second.

A third: Black men represent about 7.2% of the population, but commit almost 40% (39.6%) of all homicides.

"Even though surveys from the Department of Health and Human Services show that white and black people use drugs at similar rates (12 percent and 13.7 percent, respectively), blacks are up to five times more likely to be arrested for drug crimes, depending on the year surveyed."

Semi-serious question: what gets counted as a "drug crime"? Only simple possession? Or things like assault by a perp who happens to be carrying?

Looting a WaWa with a bag of coke in your pocket? There seems to be far less care in criminal activity these days. If I'm carrying drugs, it seems like it would be prudent to go out of my way not to get involved with the police.

The myth that it is the common drug user is in prison in prevelant. But false. Very few are in prison for simple personal use. Almost all of the prison population in for drugs is for trafficking or selling, or tagged onto another crime.

The myth is so prevelant it is hard to find the studies disproving it. But here is an example.

https://www.davealbo.com/index.php/2020/08/24/debunking-non-violent-drug-crime-myth/

So using drug use rates is also dishonest.

“Even though surveys from the Department of Health and Human Services show that white and black people use drugs at similar rates (12 percent and 13.7 percent, respectively), blacks are up to five times more likely to be arrested for drug crimes, depending on the year surveyed.”

Maybe, because one group is more careful about where they commit their "drug crimes"?

The emphasis on race when discussing criminal justice can frustrate people who see it all as a polarizing part of the culture war.

No shit.

It’s almost like the assholes behind the scenes of all this perpetual culture/race war bullshit are following a fucking textbook:

"Pick the target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it.” - S. Alinsky

One sixth of those are not crimes at all, for vices have no victims or mens rea. The LP has for 50 years published platforms calling for repeal of drug laws. Yet The Kleptocracy adds asset-forfeiture looting and immunity for killer cops and bans all the safe drugs. The Quing Dynasty did this... Nullifying laws against non-addictive drugs eliminates opiate markets. Anyone upset over the violence of drug laws need only vote libertarian. But hurry. Trumpanzee infiltrators may try to delete repeal planks and add a girl-bullying plank instead.

The misidentification problem is well-established by now

White clerks identified White customers most accurately, Black clerks identified Black customers most accurately, and Hispanic clerks identified Hispanic customers most accurately.

Setting aside that the above statement is ambiguously incorrect, it’s interesting that a problem arising directly out of and directly associated with diversity gets labeled a misidentification problem rather than a diversity problem. If we were so diverse that nobody of any race could recognize anyone well enough to attain a valid conviction, all of our problems would be solved!

Circling back to the ambiguously incorrect statement to highlight the idiocy of diversity, black clerks identified white and hispanic customers more accurately than whites or hispanics (even among themselves). So, just make black people the victims of all the crimes and our race-based witness identification will be as good as it can possibly be!

Isn't that redundant?

Convict first, ask questions later!

I wondered how long it would take for someone to report this editing cerebral flatulence.

And, not to be pedantic, but exonerated isn't the same as didn't do it. There are still innocent people in jail, and guilty people free. Over reacting to this takes focus an resources from fixing bigger issues. Like how many homicides are unsolved.

End blanket prosecutorial immunity.

Or put PDs in jail? I mean, the issue isn't just bad prosecutors, but bad defenders.

Sure there are incompetent PDs but even the best lack the resources available to prosecutors.

I guess the US has affirmative action in college admissions and prison admissions.

Aren't blacks 50 percent of prisoners? Don't these sorts of organizations target minorities for help with exonerations? Aren't white people rich and can afford better lawyers so there are fewer railroadings?

White people have White Privilege. They never go to jail.

87% of the Black population identify as Democrats.

70% of the Prison population identify as Democrats.

70% of 87% = 61% expected to be in prison.

The world makes sense after all.

You cannot brainwash people that they are entitled to STEAL and expect them to stay out of prison. F'En Nazi's.

The difference is just 14 percentage points, but when you account for the greater number of black exonerations, official misconduct played a role in twice as many convictions (500 blacks to 236 whites) documented in the registry. And the study attributes the difference in the rate almost entirely to police misconduct.

--------------------------------------

I'm shocked. Shocked, I tell you !

Why? Here's my guess. The people working to free innocent prisoners are more interested in the cases of blacks than whites.

Or alternatively, prosecutors work harder at white convictions making better cases that resist being overturned. With a black defendant the prosecutor can count on systemic bias to aid the conviction allowing a sloppier case.

You don't have to prove that you are both biased and ignorant by writing biased and ignorant opinions.

Yes, it's a guess! Like coin toss? Ratiocination might lead one to intuit that the black person may be more likely to have evidence planted against him or, the black person couldn't afford an attorney and end up with a work-overloaded "court appointed attorney".

"The people working to free innocent prisoners are more interested in the cases of blacks than whites."

Exactly, and it is because of the twin lies that "we are committing mass incarceration" and that "blacks are overrepresented in prisons".

You may have a point there.

whites are being discriminated against by being left in jail?

One of the oldest and most consistent findings of systematic studies of eyewitness identification is that white Americans are much more likely to mistake one Black person for another than to mistakenly identify members of their own race."

I won't deny the is an issue here but it is not this simple. There are a full spectrum of hair and eye colors in whites; the majority of black men and women have brown eyes and brown hair. White skin reflects light differently than black skin. An APB for whitey typically has a lot more specific information.

With the exception of sexual assault I assume we are talking about situations where a crime was unambiguously committed. The desire to get their man is in play, but the desire to get a black man is not such a simple inference. This is more complicated than The National Registry of Exonerations wants it to be.

I’m sorry, Scott, but are you really that stupid or do you think readers are that stupid? Others have already pointed out the idiocy of that "analysis", so I'm not going to repeat it.

That’s because many of those “exonerations” are probably based on claims of racial bias.

Let’s also be clear here: most “exonerations” don’t mean that the person didn’t commit a crime, it simply means that either they committed a lesser crime, or that there was a procedural error in their conviction, or that they couldn’t be found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Guess that assumption of innocence I hear so much about get thrown out the window. What you are saying is they are guilty it's just a technicality that their conviction did not hold.

Guess that assumption of innocence I hear so much about get thrown out the window. What you are saying is they are guilty it’s just a technicality that their conviction did not hold.

Your illiteracy is biting you on the ass again. No, that's not what he's saying.

I am saying that in many cases be based on a technicality or reasonable doubt.

For you to portray my statement as a “they are” kind of statement is dishonest and manipulative of you.

The “presumption of innocence” just means that the government has to prove guilt (as opposed to the defendant having to prove innocence), nothing more.

But what matters here is the burden of proof. In criminal convictions, it means that guilt needs to be proven “beyond a reasonable doubt”. That standard means that many people who are not legally guilty did, in fact, commit the crime they were charged with.

In fact, many people who are found criminally “not guilty” of a crime are nevertheless held responsible for that crime in civil court, where the burden of proof is lower.

Consider the source. For it, the only factor is apparently that of outcome based on skin color. The possibility that the people being exonerated may be guilty is of no concern. The possibility that the program is racist is of no concern. The fact that other inmates may be far more deserving of assistance certainly seems to have been missed. M4e is not much of a thinker.

Guess that assumption of innocence I hear so much about get thrown out the window.

Once convicted, yes. We should still err on the side of innocence, but the presumptions have been definitively addressed and dispensed with.

This article (and the underlying study) opens with a statistical fallacy. The ratio of exoneration (by race) to the total population is irrelevant. The relevant ratio is exonerations compared to convictions by race.

The article is on stronger ground when it gets to findings about discrepancies in the latter ratio but the difference is not nearly as striking and may not even be statistically significant given how finely they had to slice and dice their data to make their desired points.

Yes, the Drug War is evil and yes its evils have landed heaviest on disenfranchised subsets of the population. You don't need carelessly sloppy statistics to make that point.

You only have to youtube or google exonerations for about 15 mins before you start to notice that the evidence for convicting a black person can be flimsy as all heck and still work. Everybody / anybody can be the victim of a well orchestrated railroading , but it seems like a lot of freedom stealing against minorities (especially black) takes only bare minimalist effort to be successful for years.

You'll find the same is true for anyone who cannot afford a decent lawyer. Income level or class is likely a better way to look at who is likely to suffer most at the hands of the judicial system.

Why Are Half of All U.S. Exonerations of Black Prisoners?

Because, to the organizations that do 'exonerations' there's far more political clout to be gained by 'exonerating' black people than anyone else.

Why Are Half of All U.S. Exonerations of Black Prisoners?

Why are the overwhelming majority of exonerations men (not a biologist, just quoting the The National Registry of Exonerations)? Is "the system" railroading people-of-prostates or is "exoneration rate" a topic the statistically challenged social scientist should shy away from? Why am I asking so many questions?

This isn't very difficult to grasp unless you are a mindless sheep. Blacks are disproportionately exonerated because commit disproportionately more crime. Derp Derp Derp

What a dishonest article. I haven't seen a statistic murdered this gruesomely since Biden reduced the deficit by slowing down the spending he created.

A more important question is:

Why do African-Americans murder each other at ten (10) times the rate that White-Americans murder each other?

(Removed cuz not meant to be response. Cant remove fully, would just leave blank comment as i just saw)

Perhaps the high rate of exonerations of black prisoners is a function of the racial and political biases of the types of people who do the legal work of exoneration? In my experience, most of them lean heavily into the ‘woke left’ camp. In my experience, they seem to get a bigger thrill helping minority victims of the Great White Patriarchy (whether innocent or not) and don't think of white people as potential 'victims' of anything. The more downtrodden the minority, the more it assuages their White Guilt and balances the Patriarchy's rigged scales of justice.

I was railroaded for a violent crime based on crooked cop and a stranger’s testimony that I assaulted him. Truth is, he attacked me with an axe. Not a scratch on him, so should’ve been an easy case to tear apart with minimal legwork. Legal aid seemed interested…until they saw I was a white male, and then in so many words invoked my ‘white privilege’ as suddenly tempering their zeal to help me.

Of course, plenty of Americans are wrongfully convicted for a variety of reasons, and the Drug War is a disaster that should done away with immediately.

Scott Shillford bustin’ statistics 101 to write an article and make a dime. News at 11.

What % of exonerations are men? Over 90%? OMG… what does that mean? That police must have a bias against men? No… it’s just that over 93% of all prisoners are men. Blacks account for nearly half of all US prisoners. They commit more than half of all homicides. So the fact that they account for half of all exonerations is EXACTLY what we’d predict statistically. Exonerations have nothing to do with overall population demographics… they’re related to prison demographics. So it doesn’t matter if blacks are only 15% of the population (they are, in fact, less actually)… what matters is what % of the PRISON population they are.

I'm not sure if you're being openly dishonest or if you're just stupid. I really hope it's the second one.

I think openly dishonest to manufacture an “idea” for an article and make a couple bucks.

how are you going to talk about the percentage of exonerations compared to the general population and not even mention the percentages in the races in prison? Whether or not that is all on the up and up is another discussion, but it seems natural that half of the exonerations are black if half the prison population is black. Does Reason think we are stupid? I am still praying for the day when libertarians can get their crap together so I have someone worth voting for.

Maybe because they commit the majority of crimes! As per FBI statistics. Oh n call me a racist…I don’t give a fuck.

I have little doubt that there is something there to talk about... but the way this data is presented is so deliberately misleading, it is difficult to even take this seriously.

Nobody accidently says "Black people represent less than 15 percent of the U.S. population, but they account for more than half of all exonerations" as the lede accidentally. That is deliberately misleading, to the point that trust has been broken between the reader and the author.

By putting that nonsense as the lede, you announce loudly that you are lying. So even if your intent is honest, no intelligent audience would hear you out. Nobody who writes that as their opener intends to honestly inform the reader.

Considering that the majority of inmates are black it's not surprising in the least bit. The USA incarcerates far too many citizens and often for the crime of being too poor to defend themselves. The USA has far too many laws where every citizen accidentally and unaware will commit a "Crime" every day.

Maybe it’s because of: https://cwbchicago.com/

https://www.foxnews.com/us/philadelphia-high-school-student-14-dead-quadruple-shooting-after-football-scrimmage

Gee I don't know--maybe because the vast majority of heinous crimes are committed by these vile animals---most of whom can't seem to be able to walk more than three steps without stopping to rape, rob, beat, or murder someone?

You racist bastard.

I did notice that the racial breakdown of those convicted of the listed crimes isn’t given (except for murder, where the number imprisoned and the number convicted are presumably the same). We are told the percentage of blacks among those prosecuted for rape, and among those imprisoned for murder, but the only racial breakdowns given for other crimes are the percentages among those exonerated after conviction. Similar breakdowns for (1) those indicted for or charged with such crimes, and (2) those convicted of such crimes, could be useful in evaluating those stats for the exonerated.

“Why are so many blacks criminals?” ... At least a PARTIALLY true answer is "because it is criminal to be black!" Driving while black, jive-talking while black, "acting disrespectful" (AKA "acting black") in front of a LEO, and, last but not least... BLOWING UPON A CHEAP PLASTIC FLUTE (in an unauthorized manner) while black!

Stay ye SAFE from the Flute Police!!!

To find precise details on what NOT to do, to avoid the flute police, please see http://www.churchofsqrls.com/DONT_DO_THIS/ … This has been a pubic service, courtesy of the Church of SQRLS!

Duh. Thomas Jefferson.

At least the cops won't handcuff them to railroad tracks.

https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2018/crime-in-the-u.s.-2018/topic-pages/tables/table-43

Right Sqrlsy, all those white folks be killing black people and just leaving the neighborhood with none the wiser. Or, you dumb piece of cat shit, homicide rates are a good indicator for general criminality of a populace since bodies dropping are harder to cover up than anything else.

Some cops are named Snidely Whiplash

Go look at the arrest data.

40%+ of the violent crimes are committed by black men who make up 6.5% of the population.

https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2018/crime-in-the-u.s.-2018/topic-pages/tables/table-43

I just worked part-time from my apartment for 5 weeks, but I made $30,030. I lost my former business and was soon worn out. Thank goodness, [asn-07] I found this employment online and I was able to start working from home right away. This top career is achievable by everyone, and it will improve their online revenue by:.

.

EXTRA DETAILS HERE:>>> https://extradollars3.blogspot.com/

So if 40% of prisoners are black men, and they get 50% of the exonerations, aren't they ahead of the game?

-jcr

I work from home providing various internet services for an hourly rate of $80 USD. I never thought it would be possible, but my trustworthy friend persuaded (emu-054) me to take the opportunity after telling me how she quickly earned 13,000 dollars in just four weeks while working on the greatest project. Go to this article for more information.

…..

——————————>>> https://smart.online100.workers.dev/