Gerrymandering Is Making Elections Less Competitive

Cynical single-party gerrymandering contributes to and is driven by the hyperpartisanship that defines American politics right now.

By the time voters go to the polls in November's midterm elections, the vast majority of congressional races will have effectively been decided.

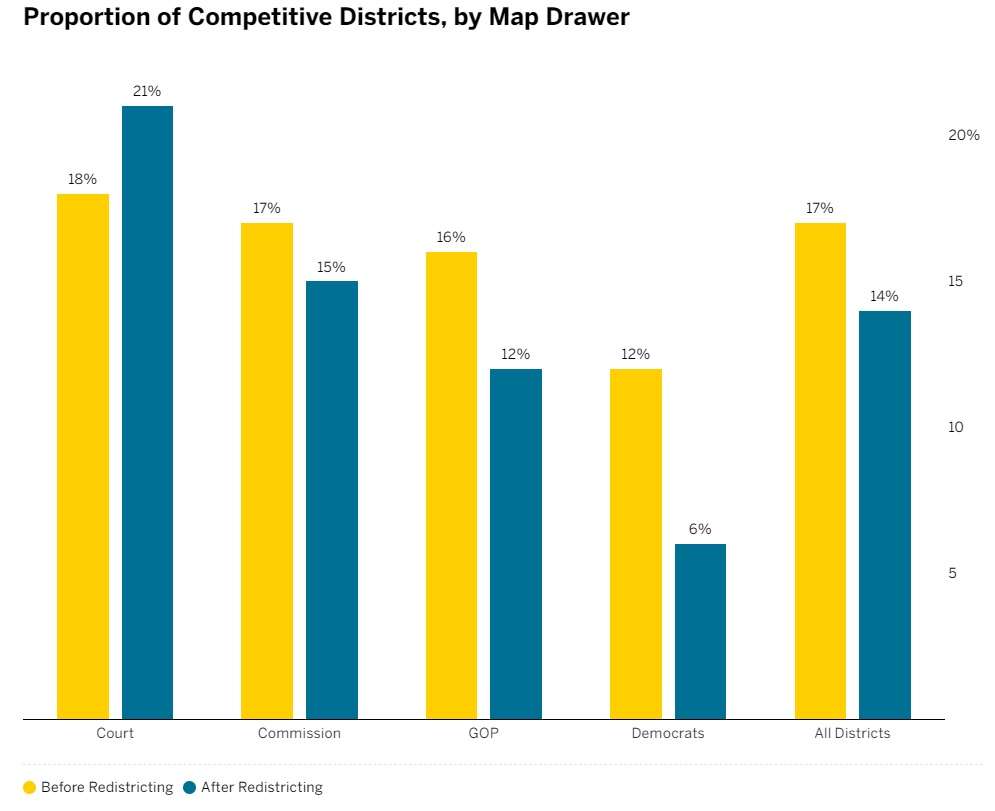

That's because the number of competitive congressional districts has declined sharply since two years ago, thanks to the bipartisan effort at carving safe seats during the once-per-decade redistricting process. Under the new congressional maps recently approved by state governments, there will be just 60 districts (out of 435 in total) that would have been decided by fewer than eight percentage points in the 2020 election, according to a recent analysis from the Brennan Center for Justice, a pro-democracy think tank housed at New York University.

Both Republican-drawn and Democrat-drawn maps trended toward less political competitiveness during the most recent round of redistricting, according to the Brennan Center's review. But the decline in the overall number of competitive seats was more noticeable in states where Democrats controlled the mapmaking process. In those states, just 6 percent of all congressional districts are competitive, down from 12 percent previously.

To understand why this happens, take a look at Illinois—where the new congressional map was drawn by the Democrats who control the state Legislature. As I wrote last year, Democrats were focused on packing as many of the state's Republican voters into as few districts as possible, thus maximizing the number of districts where Democrats would be favored to win. The result is three deeply red districts and 14 blue districts, many of which are nearly impossible for Republicans to hope to win—though a few of them rate as barely competitive. The map got a grade of "F" from the independent Princeton Gerrymandering Project, but fairness isn't the goal of the partisans who control redistricting in many states. Maximizing victories is.

But that means many voters don't get a meaningful say in who represents them in Washington. Cynical single-party gerrymandering contributes to—and, circularly, is driven by—the hyperpartisanship that defines American politics right now.

"As a district leans further toward one party or the other, the general election becomes increasingly insignificant while the favored party's primary becomes the real contest," write Brennan Center analysts Michael Li and Chris Leaverton. "As a result, primary voters can effectively decide which candidate will represent the district in Congress, even though they make up a small fraction of the electorate and are often far more partisan than the average general election voters."

That effect is compounded in states where strict ballot access laws limit the ability of third-party and independent candidates to compete as well. The two major parties limit competition between their own candidates by drawing single-party districts, then keep anyone who can't win a Republican or Democratic primary election off the ballot as well—a pretty neat trick!

Of course, looking at the 2020 election and overlaying those results using [OK?] the new district lines is only one metric for scoring a district's competitiveness. But other measures also show that the number of contested congressional races has been declining in recent decades as both major parties have gotten progressively better (thanks to technology) at drawing single-party districts.

According to the Cook Partisan Voting Index, which scores each congressional district along a Republican/Democrat axis based on registration totals and recent election results, the number of swing districts has been shrinking dramatically. In 1998, there were 105 districts rated "hyper-competitive"—that is, with a rating of between R+3 and D+3—in the Cook system. Now, there are only 45.

Yes, efforts to "fix" redistricting are imperfect at best, but attempts to make the process even marginally more legitimate in the eyes of the public should be taken seriously.

The alternative is the current scenario where a few handfuls of districts scattered across the country effectively determine which party controls Congress. Giving voters fewer choices might benefit the powerful political parties who rig the game by carefully gerrymandering districts—but like in any market, monopolies aren't great for the public.

Show Comments (139)