Voters Approve Redistricting Reforms in Colorado, Missouri, Michigan (and Maybe Utah, Too)

Taking redistricting power away from lawmakers isn't a foolproof strategy for ending gerrymandering, but it's probably a modest step in the right direction.

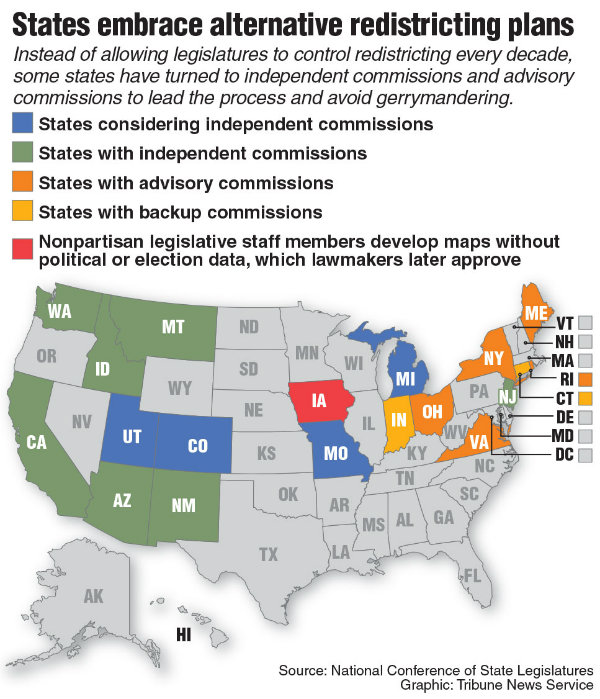

Voters in three states—Colorado, Michigan, and Missouri—approved ballot measures Tuesday that will transfer some redistricting authority away from state lawmakers by creating independent commissions for the purpose of redrawing congressional and state legislative district lines after the next census.

The three measures approved Tuesday vary slightly from state to state, but the general consensus across all three states, where the initiatives got more than 60 percent approval, seems to be that voters are interested in trying a new approach to one of the most important and most political aspects of American democracy. (In Utah, a similar ballot initiative to create a redistricting commission remained too close to call on Wednesday afternoon. With 74 percent of precincts across the state reporting, "Yes" had a narrow 4,000-vote lead.)

Colorado's initiative would create a 12-member commission for the purpose of redrawing congressional districts. Half of the members would be selected by a panel of state Supreme Court justices, and half would be selected by the majority and minority leaders of the state legislature. Speaking of: Rocky Mountain voters also approved a separate ballot question to create a different 12-member commission to redraw state legislative districts. Under the ballot initiatives, the commissions would each include four registered Republicans, four registered Democrats, and four people who "will not be affiliated with any political party."

That wording seems to exclude members of third parties, something that has rankled the state's Libertarian and Green parties, as Reason has previously reported.

Michigan's redistricting initiative would create a similar scheme. The new, 13-member redistricting commission would have to include four Democrats, four Republicans, and five independents or members of third parties. Passing a new redistricting plan will require the approval of at least seven members, including at least two Democrats, two Republicans, and two of the other members.

Missouri's redistricting reforms were included in an omnibus ballot question that also included changes to the state's lobbying laws and imposed campaign finance restrictions for state legislative candidates. The measure creates a new, nonpartisan position known as the state demographer, who will be appointed by a consensus of the state auditor and Senate leaders from both parties. The state demographer will provide a series of redistricting options for state lawmakers to choose between—rather than allowing legislators to draw their own.

Limiting redistricting is a worthwhile project that could produce more competitive House elections and help nudge American politics away from the fringes. When so many districts are carved to give one party or the other a clear advantage, it makes low-turnout primary elections more important and encourages politicians on both sides to pander more to their own parties' outer flanks than to the ideological middle, where most voters reside.

That said, handing redistricting power to a so-called independent commission is not a foolproof strategy for fixing gerrymandering.

The same political pressures that cause state lawmakers to draw districts that favor one major party or the other are still present, and some redistricting commissions have actually done a worse job of drawing competitive districts that the state legislatures they replaced. Who ends up being appointed to those commissions, how they are picked, and what oversight (from courts, for example) exists are probably more important than the simple fact that a commission has been created.

Several other states—most notably California, Arizona, and Iowa—experimented with redistricting commissions in 2010, and legal challenges to legislative-drawn maps in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and North Carolina reached the Supreme Court last year, further raising the profile of redistricting battles.

It also won't put an end to partisan complaints—primarily from Democrats—about the makeup of House districts. It's true that gerrymandering played an important role in giving the GOP an advantage in House races since 2012, but other geographic factors—like the fact that Democratic voters tend to be concentrated in cities—would give Republicans an advantage even if all districts were more compactly drawn.

That's not an argument against mechanisms that result in more compact districts, of course, but merely a function of the fact that the two major parties have essentially divided along urban/rural lines.

Still, it probably makes sense to remove that power from the direct control of state legislatures, particularly in places where they have wielded it irresponsibly. Doing so may, in some small way, increase the level of trust the public has in the redistricting process.

Show Comments (41)