How Stalin Toyed With Mikhail Bulgakov

The author of The Master and Margarita faced a bewildering mixture of rewards and censorship.

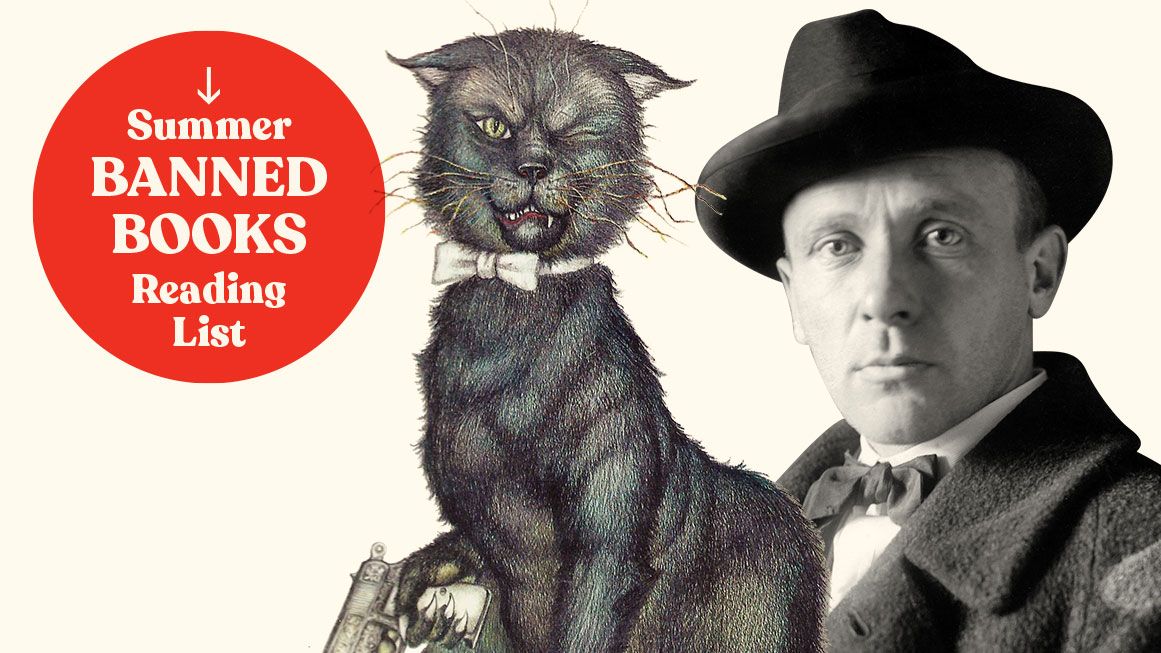

The devil went down to Moscow not long after the Bolshevik takeover, along with a valet, a vampire, an assassin, and a gunslinging man-sized cat called Behemoth. That's the setup for Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita, a scathingly satiric tale of Soviet censors, informers, and intellectual courtiers that doubles as an unorthodox retelling of the Book of Matthew. Finished in 1940, the novel was not formally published until the late 1960s, and then only in heavily censored form. The full novel finally appeared in 1973, but even then Russian readers were more likely to encounter a samizdat edition than the hard-to-find official printing.

Bulgakov had the misfortune of being a writer in the Soviet Union—worse yet, Josef Stalin's Soviet Union. The dictator took a personal interest in the author, much as a sociopathic boy might take a personal interest in a pet he alternately rewards and tortures. Stalin admired some of Bulgakov's plays (he reportedly watched The Days of the Turbins more than a dozen times), was known to intervene on his behalf, and refrained from imprisoning the man even when his work mocked the state. But that didn't mean the mockery always made it to the stage or page: He constantly censored Bulgakov as well. At one point, hoping to lighten the repression, Bulgakov wrote Batum, a glowing play about Stalin to be performed on the dictator's birthday. Stalin responded by banning Batum too.

Paradoxically, the censorship freed Bulgakov to make The Master and Margarita as subversive as possible: Once he realized the book was unlikely to appear in his lifetime, he poured ideas into it that he could never say publicly. And eventually it found an enormous audience. When I visited Russia in 1995, it seemed like everyone I spoke with about it had read it. One woman told me she knew people who carried a copy wherever they went.

Much of the novel's action takes place at a Moscow apartment where Bulgakov had lived, and his fans have made the site a shrine of sorts. This began illicitly in the '80s: They started leaving graffiti in the stairwell, returning to redecorate the walls whenever the authorities whitewashed them. By the time I stopped by, the apartment had become a formal tribute filled with Master-inspired paintings. But the stairwell was still covered with graffiti, some of it opposed to Russia's war in Chechnya. The dissent, it seemed, had spilled out of the book and onto the walls below.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Master and Margarita."

Show Comments (25)