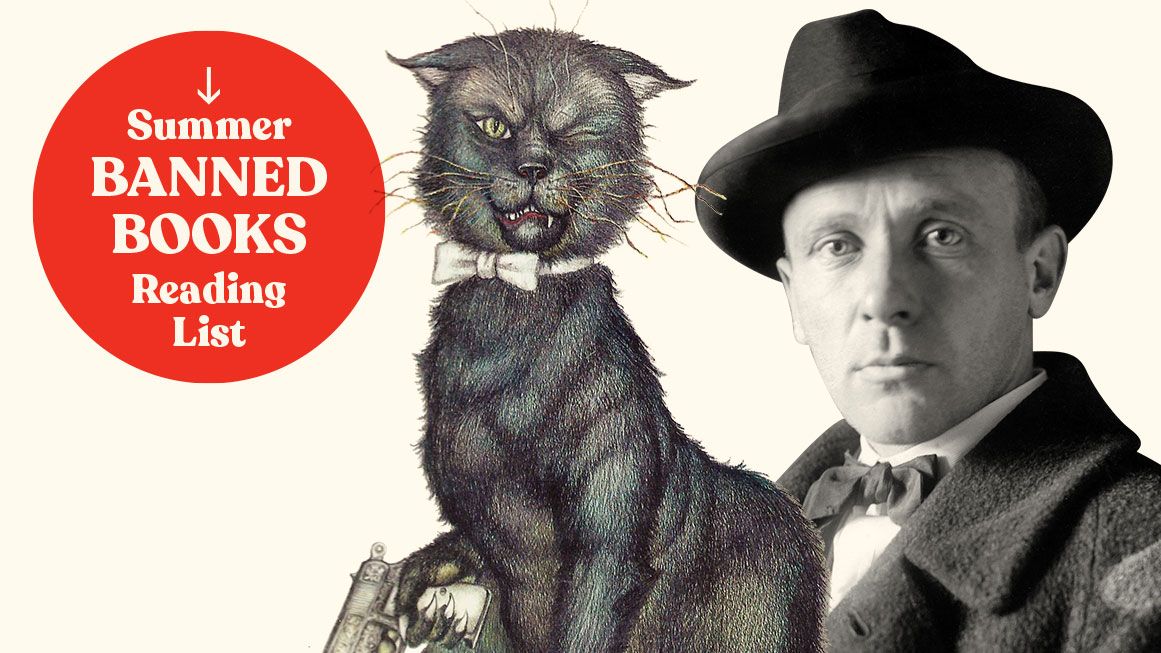

How Stalin Toyed With Mikhail Bulgakov

The author of The Master and Margarita faced a bewildering mixture of rewards and censorship.

The devil went down to Moscow not long after the Bolshevik takeover, along with a valet, a vampire, an assassin, and a gunslinging man-sized cat called Behemoth. That's the setup for Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita, a scathingly satiric tale of Soviet censors, informers, and intellectual courtiers that doubles as an unorthodox retelling of the Book of Matthew. Finished in 1940, the novel was not formally published until the late 1960s, and then only in heavily censored form. The full novel finally appeared in 1973, but even then Russian readers were more likely to encounter a samizdat edition than the hard-to-find official printing.

Bulgakov had the misfortune of being a writer in the Soviet Union—worse yet, Josef Stalin's Soviet Union. The dictator took a personal interest in the author, much as a sociopathic boy might take a personal interest in a pet he alternately rewards and tortures. Stalin admired some of Bulgakov's plays (he reportedly watched The Days of the Turbins more than a dozen times), was known to intervene on his behalf, and refrained from imprisoning the man even when his work mocked the state. But that didn't mean the mockery always made it to the stage or page: He constantly censored Bulgakov as well. At one point, hoping to lighten the repression, Bulgakov wrote Batum, a glowing play about Stalin to be performed on the dictator's birthday. Stalin responded by banning Batum too.

Paradoxically, the censorship freed Bulgakov to make The Master and Margarita as subversive as possible: Once he realized the book was unlikely to appear in his lifetime, he poured ideas into it that he could never say publicly. And eventually it found an enormous audience. When I visited Russia in 1995, it seemed like everyone I spoke with about it had read it. One woman told me she knew people who carried a copy wherever they went.

Much of the novel's action takes place at a Moscow apartment where Bulgakov had lived, and his fans have made the site a shrine of sorts. This began illicitly in the '80s: They started leaving graffiti in the stairwell, returning to redecorate the walls whenever the authorities whitewashed them. By the time I stopped by, the apartment had become a formal tribute filled with Master-inspired paintings. But the stairwell was still covered with graffiti, some of it opposed to Russia's war in Chechnya. The dissent, it seemed, had spilled out of the book and onto the walls below.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Master and Margarita."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Oh, if he wasn’t imprisoned, then he wasn’t really censored. The government just told the printer not to print it, and that was totally Muh Pryvit Companeez decision

That rule only applies when Democrats do it.

I wonder how well any of his work translates well, into either a different language or to the current times. Seems to be pretty specific to the time and place. Maybe Putin's Russia is close enough to work there now, but an English translation might need a lot of explanatory notes to make much sense. I suppose that is one indication that modern America is not as bad as Stalinist USSR.

"I wonder how well any of his work translates well, into either a different language or to the current times. Seems to be pretty specific to the time and place."

You don't need to wonder. You can read Bulgakov's work. Some of the references may be obscure. Behemoth carries around a primus stove, which was in common usage but not seen by the public as a desirable substitute for proper cooking apparatus. If the full length Master and Margarita seems too daunting, the short story Heart of Dog is just as sharply satirical, about some of the Bolshevik's crackpot medical theories.

Master was a good book. You just have to keep a notepad with you to keep track of things,

Heart of a Dog is my favorite—and I think a lot of folks here would both get and appreciate it. Hardest hit: everyone who thinks Communism can be “gotten right”

It's further down my list. Right now I'm busy relaxing with Arturo Perez-Reverte. I may read Darkness at Noon next.

Incredibly I myself haven’t read Darkness At Noon wt. (I think it got eclipsed by Vasily Grossman’s novels)

How am I to compare it with the original, if I can't read the original?

How am I to read it with his experience, when the time and place are inaccessible to me?

How am I to read it with his experience, when the time and place are inaccessible to me

Hang around here for a few more years.

I’ve read both. Like so much good Russian prose, it translates very well in the hands of a capable translator. Now great Russian poetry (not just Pushkin but Akhmatova, Mandelshtam Yesenin et al…well yeah. No translation does the original justice.

an English translation might need a lot of explanatory notes to make much sense

It's very accessible, actually. I recommend it highly. (And as mtrueman says, Heart of a Dog is good too.)

Heart of a Dog was mad into a god movie too—I watched and laughed heartily with my Russian friends in St Petersburg summer of 92. I don’t know if it’s available with English subtitles. The actors who played Sharik and Filip Filipovich were superb.

Good to hear. I might check this one out.

Makes me think, though. The translation can sometimes make all the difference in these things. Have you ever read the Three Body Problem? Chinese sci-fi, and a lot of what happens in the setup revolves around Mao's time, struggle sessions, the great leap forward, and just general Chinese common knowledge. The translator was extremely good at footnoting things that any Chinese reader would know, culturally.

"Bulgakov had the misfortune of being a writer in the Soviet Union—worse yet, Josef Stalin's Soviet Union."

Perhaps writing under Lenin, who banned newspapers the first day he took power, would have been worse. Stalin had something of a soft spot for writers, had his poems published, and had worked as an editor and translator as a young man. In power he overturned Lenin's ban on Dostoevsky and green lighted Russia's first Korean language newspaper.

Bulgakov was censored but he lived, and continued to write. Isaac Babel, a huge literary figure in the days after the revolution, stopped writing in the 30s, and was caught up and executed in the purges on false charges of Trotskyism. Killed, essentially, not for what he wrote, but for not writing, not fulfilling his literary quota.

Isaac Babel, a huge literary figure

Towering, one might say.

With a name like that, there's no way his story ends badly.

I agree that Stalin treated writers with relative forbearance.

Probably Mandelshtam was arrested only because he goaded Stalin with a personal attack, called by a fellow writer a "suicide note."

(Look up "Stalin epigram" in Wikipedia.)

(2) Babel' may have paid with his life for personal involvement with NKVD (secret police) chief N.I. Yezhov and especially Yezhov's wife Khayutina. Yezhov fell severely out of favor in 1939 (by all reckonings deservedly) and brought down all his associates with him.

Bulgakov is lucky that Stalin merely toyed with him. Others (including Babel) died or killed themselves.

Btw, the US had a sort-of playboy Ambassador in Moscow, a Philadelphian named Bullitt. His wild embassy parties, to which writers (incl. Bulgakov) were invited, were the inspiration for the New Year's Eve party in The Master and Margarita. I was a Russian language student when that wonderful novel was first published. I recall that it spent 27 years in Glavlit, the Soviet censors, the longest time ever for a work.

Stalin did enjoy his cat and mouse games with writers—including calling them at home. You’d answer the phone and an operator would say, “Please hold for Comrade Stalin…” After but a couple of clicks you’d hear the all too familiar piping high voice …

One infamous instant (the great Poetess Anna Akhmatova was there and confirmed it)—After the arrest f the poet Osip Mandelshtam (who died in a transit camp soon after) Stalin called the poet Boris Pasternak (Dr Zhivago, anyone?) at home to query him on his own relationship with Mandelshtam. At the very end of the call, Pasternak said: “Listen, Iosif Vissarionovich, whenever it would be convenient for you zI would like to sit down with you face to face for a discussion.” After a phase, Stalin asked, “On what topic?” Pasternak replied, “On the topic of life and death.” There was another, longer pause and then the sound of Stalin slowly hanging up the receiver. Pasternak suffered no reprisals, but he couldn’t one that at the time. (Unpredictability was part of Stalin’s mind games.$

Stalin's favorite writer was probably Ernest Hemingway. Or at least whoever was running the NKVD in the 40's, when he was on their payroll.

(not making that up, BTW)

From what I understand - this book inspired the song Sympathy for the Devil.

https://www.masterandmargarita.eu/en/05media/stones.html

Stalin took a nation of peasants and turned them into a super power.

40+ years of trickle-down/supply-side Satanomics, aka Conmanitalism, is taking a super power and turning it into a nation of peasants.

Tsar Nicholas II bequeathed a semi-industrialized Russia to Lenin and Stalin, with a good rail network and the industry to support it. Stalin would be good at building steel mills and tanks (useful for fighting Hitler in 1941-1945), but was far less good for the peasants, reducing them to serfs on backward collective farms.