American Steelmakers Are Still Defending Trump's Tariffs That Crushed Consumers

Any gains seen by the steel industry from tariffs have been overshadowed by the losses for downstream companies and higher prices for consumers.

To hear lobbyists from the steel industry tell it, President Donald Trump's decision in 2018 to impose 25 percent tariffs on foreign steel is just about the only thing keeping American steelmakers in business.

"The domestic steel industry was in a state of crisis" before the tariffs, according to a statement submitted by the Steel Manufacturers Association in advance of tomorrow's U.S. International Trade Commission hearing focused on the economic consequences of those tariffs (and others) four years after they were imposed. "The industry was in a tailspin," a separate statement from Nucor, one of America's largest steelmakers, argues.

But data Nucor submitted along with that statement seems to call into question some of those dramatic claims.

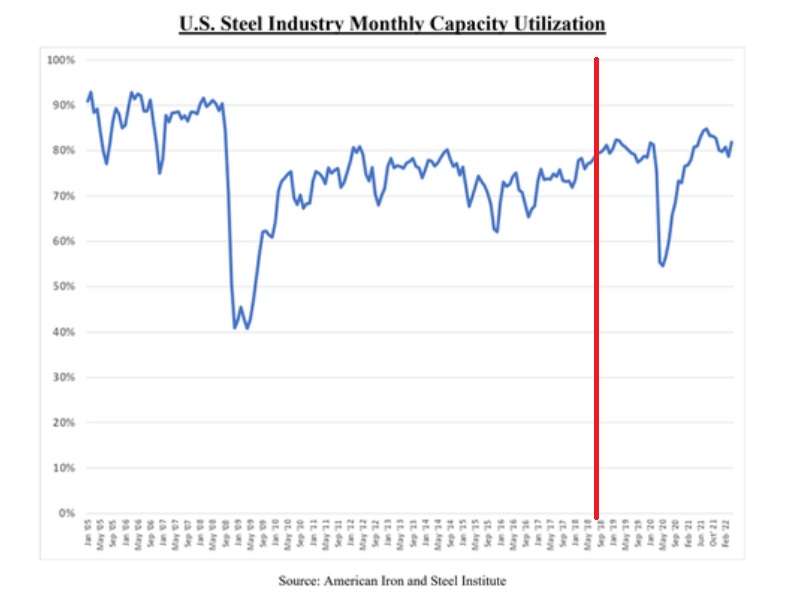

For example, here's a chart showing the American steel industry's monthly capacity utilization—a measurement of how much production capacity is running every month—with an added red line showing when the tariffs were imposed. See if you can find the "tailspin" that necessitated an expensive government intervention:

Lobbyists from steel companies like Nucor and trade groups like the Steel Manufacturers Association are set to testify at Thursday's hearing alongside small businesses and other trade groups that have been harmed by the higher prices created by the tariffs Trump imposed and that Biden has maintained. Those tariffs have shielded the American steel-making industry from some foreign competition, boosting profits and allowing for some marginal growth in terms of capacity and employment.

Those marginal gains have been offset by huge increases in steel prices—increases that have been passed along to steel-consuming industries and, ultimately, to consumers.

Before the tariffs were imposed, a 40-foot-by-60-foot steel building would have cost about $25,000, according to General Steel Corporation, which turns raw steel into finished products. Now, that same structure would cost more than $30,000.

Scott Buehrer, president of Indiana-based metal fabrication business B.Walter and Co., says his company has seen steel prices nearly triple since tariffs were imposed.

"This puts U.S. industrial users of steel in a tough position of deciding how much of the steel cost increase to pass onto their customers," Buehrer wrote in testimony submitted to the ITC in advance of tomorrow's hearing. "Pass along too much of it and risk losing business to foreign competitors who have access to steel at half the U.S. cost. Pass along too little of it and your factory generates insufficient revenue to cover its cost which is not a sustainable situation."

"Any gains seen by the steel industry from the tariffs have been overshadowed by the losses in the companies downstream," sums up Stuart Speyer, president of Tennsco LLC, a Tennessee-based metal fabrication firm, in testimony to the ITC.

Rather than engage with the realities created by tariffs—including higher prices that have rebounded through the economy and helped stoke inflation—the steel industry's approach to the ITC's review relies on denying that the problem even exists.

While critics of the tariffs have claimed downstream industries and consumers are bearing higher costs, the Steel Manufacturers Association argues in its filing with the ITC, "the reality is that these measures have supported the steel industry's recovery without any meaningful negative impact on either consumers or inflation."

The word "meaningful" is doing a lot of work there, considering the piles of anecdotal evidence—from businesses like the ones owned by Buehrer and Speyer—and academic studies that have concluded the exact opposite. Indeed, in the very next sentence of the group's testimony, the Steel Manufacturers Association admits that tariffs resulted in rising steel prices (the group argues those increases were only temporary).

If you discard higher prices as a "meaningful" impact of tariffs—which exist only to force prices to rise—then it is easy to look at the past four years and conclude that American steelmakers have reaped the benefits of a protectionist trade policy with no significant trade-offs. But that's an obviously misleading assessment of the past four years—one that the ITC ought not to believe.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Does Koch Industries ask for these sorts of stories to be written, or do Reason writers just know?

I without a doubt have made $18k inside a calendar month thru operating clean jobs from a laptop. As I had misplaced my ultimate business, I changed into so disenchanted and thank God I searched this easy task (neh-07) accomplishing this I'm equipped to reap thousand of bucks simply from my home. All of you could really be part of this pleasant task and will gather extra cash on-line

travelling this site.

>>>>>>>>>> http://getjobs49.tk

How dare you publish another article describing The Con Man's big government ways.

Trump is the most dreamy libertarian since George W. Bush according to his cult.

How dare you continue to normalize pedo behavior on this site.

A few years back you posted kiddy porn to this site, and your initial handle was banned. Rather than follow the will of Reason’s staff, you resurrected that identity and continue to post here. A decent person would realize how abhorrent this behavior is, burn the SPB identity and return under some new handle. While that wouldn’t change your despicable appetites, it would at least respect a community’s wishes to not mix with pedophiles. But since you have no shame, the only thing I and others can do is point out your past behavior rather than converse with you.

It will never not amaze me how quickly and easily Trump broke so many people.

Sometimes it feels like every libertarian writer here learned one buzz word and dedicated their entire career around that one buzzword, without doing any type of secondary or in depth analysis to the complex issue. Then filled in the rest with twitter and journolist talking points.

It’s fascinating, isn’t it? We have literally hundreds of taxes on the books, many much larger and more destructive than steel tariffs.

If we could replace all federal taxes with tariffs, the country would be a lot better off and a lot more libertarian.

But Reason writers obsess about tariffs. Is that ignorance? Stupidity? Or is it the financial interests of their sponsors?

Steel costs more?

Why? Is it made of spittin tobaccy?

New day, same old shit...

https://reason.com/2020/01/22/trump-campaigned-on-saving-factory-jobs-but-u-s-manufacturing-just-went-through-a-year-long-recession/

Clear-cut case below, showing the UTTER FAILURE of protectionism in general, and Trumpist protectionism specifically:

Meanwhile in the real world…

https://reason.com/2019/04/22/trumps-washing-machine-tariffs-cleaned-out-consumers/

Trump’s Washing Machine Tariffs Cleaned Out Consumers

A new report finds the tariffs raised $82 million for the U.S. Treasury but ended up increasing costs for consumers by about $1.2 billion.

PROTECTIONISM DOESN’T WORK!!! DUH!!!

Protect American washing-machine makers from Chinese competition? The FIRST thing that American washing-machine makers do, is jack UP their prices… AND the prices of dryers to boot, too! To SOAK the hell out of all of us consumers!!!

From the above-linked Reason article about washing machines…

“All told, those tariffs raised about $82 million for the U.S. Treasury but ended up increasing costs for consumers by about $1.2 billion during 2018 … (deleted). Although the trade policy did cause some manufacturers to shift production from overseas to the United States in an effort to avoid the new tariffs, the 1,800 jobs created by Trump’s washing machine tariffs cost consumers an estimated $820,000 per job.”

Summary: Nickels and dimes to the USA treasury; boatloads of pain for consumers. USA jobs created? Yes, at GREAT expense! Putting these 1.8 K workers on a super-generous welfare program would have been WAY better for all the rest of us! Plus, you know the WORKERS don’t make super-huge bucks (no $820,000 per job for THEM); the goodies flow to the EXECUTIVES at the top of the washing-machine companies! The same ones who play golf with The Donald, and join him for gang-banging Stormy Daniels! Essentially at our expense!

Stupid Reason. Higher steel prices mean steel producers pay people lots of money to make steel which they use to buy stuff. Just like breaking windows, it stimulates the economy. That's why protectionism is so awesome!

Steel tariffs are a drop in the bucket compared to other taxes.

How about you apply all that sarcasm and vitriol to a repeal of what actually hurts people : the income tax and capital gains taxes?

So, eighteen months into the Biden-Harris presidency these tariffs still belong to Trump and his administration. It's as if the current administration is mired in maintaining policy or has no economic sense of its own. Which is it? When does the blame come to reside with Biden-Harris? After the midterms?

From the article... "...created by the tariffs Trump imposed and that Biden has maintained."

Both sides!!! Yes, really! They are BOTH, both stupid AND evil!

"...tariffs that crushed consumers"

I was crushed? I guess nobody told me 🙂

(Was supposed to be a new post, not a reply.)

Boehm doesn't mention the new steel mills that were to be built, thus lowering costs by having more steel produced in the US. The same mills that can't be built because of the Unions and/or environmentalists. That was the idea. Put the tariffs in place to make it economical to produce more steel in the US and lower the cost of US steel.

So, the cost of a 40x60 steeling building has gone up by about 5k. OK, is that all due to the tarriffs, or did the decimation of the economy with supply chain issues and rampant inflation play a part? Also, one question I want answered, is this building that costs a little more made with American steel? If so, I'm good with that.

To hell with shit Chinese steel, we did it best first, and we should be able to do it again. I am a huge proponent of supporting American manufacturing, and having us be major exporters, instead of having to import inferior foreign goods and getting shafted in the international markets.

And American corporations are still advocating for flooding the US labor market with cheap third world labor while pushing the resulting costs onto US tax payers. They even use organizations like Reason and Cato to do it.

Lobbying in their own interests is what corporations do. Surprise!

Eric Boehm --- Still pushing for ZERO taxes for foreign goods while completely being ignorant of the 80%+ on domestic. Still waiting for anyone at Reason to comment on the 'taxes' on a domestically created loaf of bread..