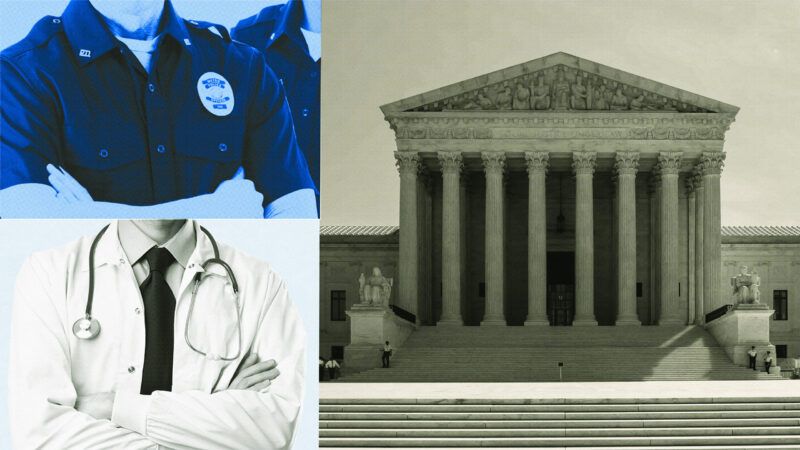

Supreme Court Tells Cops To Stop Playing Doctor

The unanimous decision is a good first step for getting law enforcement out of prescription decisions.

No one witnessing a burglary in progress would call 911 and ask for a doctor. Likewise, it makes no sense for a doctor to consult a cop about prescribing medications. Yet in the past decade, law enforcement, driven by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), has taken a large and inappropriate role in monitoring and dictating the amount and kind of pain medications doctors may prescribe. Once this threshold is crossed, doctors are subjected to tactics that would horrify anyone with even a passing knowledge of the Constitution. Fortunately, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously decided such tactics are unacceptable.

The Supreme Court reined in overzealous prosecutors who arrested doctors for treating their patients as individuals rather than conforming to law enforcement's accepted standards. In Ruan v. United States, the Court overturned a decision that would have sent board-certified pain management specialist Xiulu Ruan to prison for 21 years for not conforming to law enforcement's arbitrary and misguided standards. Ruan was not allowed to introduce expert testimony to argue that his pain management decisions were reasonable and based upon clinical experience as well as his patients' individual needs—a so-called good faith defense.

When the public hears opioids, most reflexively think of prescription pain pills. But the term opioids actually refers to a broad category of drugs, including illicit "street" fentanyl, now widely known as the most dangerous of them all. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 77,000 of the 105,000 drug overdose deaths in 2021 are opioid-related, 90 percent of which are due to illicit fentanyl. The rest are mostly due to heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine.

Although fentanyl alone can easily be lethal, the overwhelming majority of overdose deaths are "polysubstance" deaths: opioids mixed with stimulants, sedatives, and alcohol. To wit, nearly 70 percent of the fentanyl deaths also involved mixtures of cocaine, methamphetamine, and heroin, while the number involving prescription pills was only 16 percent. In 2020, CDC data showed that a mere 7 percent of fatal overdoses involved prescription opioids alone.

Apparently, the Department of Justice didn't get the memo. On June 29, just two days after the Supreme Court's Ruan ruling, the DOJ announced the formation of the New England Prescription Opioid Strike Force, targeting doctors who law officers decide are "overprescribing" opioid pain medications.

There is a term for this: Cops practicing medicine.

The timing of this strike force is curious because the opioid prescribing rate has dropped precipitously—60 percent since its peak in 2011. Furthermore, in 2019, one of us co-authored a paper in the Journal of Pain Research which demonstrated that between 2002 and 2014, per-capita pain reliever prescriptions doubled while nonmedical use of and addiction to prescription pain relievers remained unchanged. The paper's inescapable conclusion was that there is no correlation between the number of pain pill prescriptions and either nonmedical use of or addiction to these pills.

While in the past nonmedical drug users may have preferred "diverted" black market prescription pain pills (they're safer than unknown street drugs peddled by dealers), by 2018, according to a DEA report, the supply of diverted prescription opioids amounted to "less than one percent of the total quantity of pills distributed to retail purchasers." There is another term for this: Chasing the wrong suspect.

The country is not awash in pain pills—quite the opposite.

It is now evident that cops practicing medicine has been disastrous, both for doctors terrified that a strike force might burst into their clinics, and longtime pain patients who have had their medications forcibly tapered or discontinued altogether. Millions of these patients have become "pain refugees." Some, lacking other options, are forced to the street where the "medicine" they purchase is often counterfeit lookalike prescription pain pills laced with fentanyl. Worse still, suicide is becoming an increasingly common option.

Clinicians regularly debate the proper treatment of various conditions, whether hypertension, diabetes, or pain. Patients and clinical contexts vary; there is no one right way to treat any single medical condition. Lacking any medical background, the DEA and other law enforcement agents fail to appreciate this.

Fortunately, all nine Supreme Court justices did. The majority opinion stated, "the Government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant knowingly or intentionally acted in an unauthorized manner." The newly formed New England Prescription Opioid Strike Force should heed the Court's instructions.

The Supreme Court's decision is a good start. Lawmakers can build on it by requiring a warrant from the courts before police or the DEA go snooping through drug prescribing databases. Nineteen states already require this. If police officers find no evidence of a crime yet believe a practitioner's prescribing patterns fall outside the norm, they should only be allowed to report it to a state licensing board for investigation and possible discipline.

Until federal and state lawmakers stop cops from overseeing the practice of medicine, doctors will fear treating pain, and millions will suffer needlessly.

Show Comments (74)