SCOTUS Just Made It Even Harder To Sue an Abusive Federal Agent

The Supreme Court continues to shield federal officers who are accused of violating constitutional rights.

A series of recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions have made it practically impossible to sue a federal officer over an alleged constitutional rights violation. In a 6-3 ruling released today, the Court doubled down on this regrettable trend.

The case is Egbert v. Boule. At issue were the actions of a border patrol agent who sought to question one of the guests at a Washington state bed-and-breakfast about the guest's immigration status. When owner Robert Boule told the agent, Erik Egbert, to leave his property, Egbert allegedly assaulted Boule. Then, when Boule complained about the alleged assault to the agent's superiors, Egbert allegedly retaliated by asking the IRS to investigate Boule, who was audited. Boule sued Egbert for violating his Fourth Amendment rights (the assault) and his First Amendment rights (the retaliation against Boule's complaint).

In Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (1971), the Supreme Court allowed federal officers to be sued in federal court for alleged Fourth Amendment violations. Unfortunately, the Court has since narrowed Bivens to point of practically overruling it. Today's decision in Egbert v. Boule has shriveled Bivens even further.

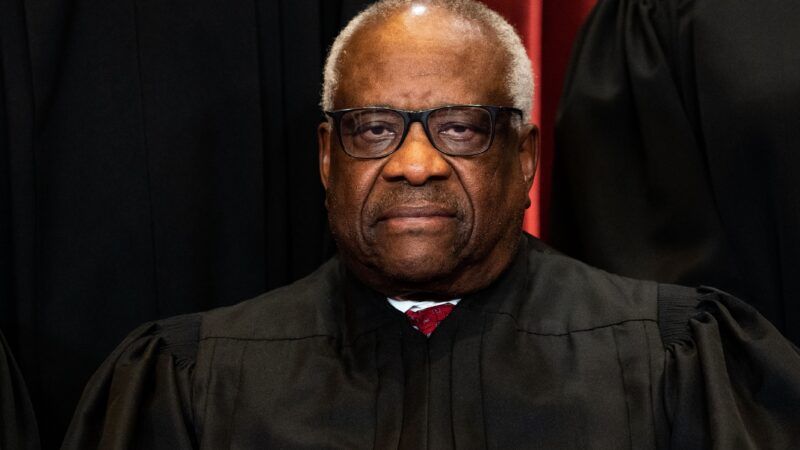

"The Court of Appeals permitted not one, but two constitutional damages actions to proceed against a U.S. Border Patrol agent," complained the majority opinion of Justice Clarence Thomas. "Because our cases have made clear that, in all but the most unusual circumstances, prescribing a cause of action is a job for Congress, not the courts, we reverse." Thomas' opinion was joined in full by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett.

Writing in dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor pointed out that Thomas' decision was plainly at odds with Bivens. "Boule's Fourth Amendment claim does not arise in a new context," she wrote, joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan. "Bivens itself involved a U.S. citizen bringing a Fourth Amendment claim against individual, rank-and-file federal law enforcement officers who allegedly violated his constitutional rights within the United States by entering his property without a warrant and using excessive force. Those are precisely the facts of Boule's complaint."

Justice Neil Gorsuch agreed with Sotomayor about that. "The plaintiff is an American citizen who argues that a federal law enforcement officer violated the Fourth Amendment in searching the curtilage of his home. Candidly, I struggle to see how this set of facts differs meaningfully from those in Bivens itself." Still, Gorsuch concurred with Thomas, arguing that the officer should win this case because Bivens should be overruled outright.

The upshot of today's ruling is that federal officers, who already enjoy extraordinary protections against being sued over alleged rights violations, are now more untouchable than ever.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

WTF does this actually mean? Is he saying that Constitutional rights are meaningless unless Congress passes a law creating criminal statutes protecting them?

And as much as I despise common law and its libraries full of dusty casebooks, isn't creating common law what judges do all the time?

I usually have enough respect for Thomas to think I must have missed something. But not here. This makes no sense to me.

Exactly. A man’s home is his castle…unless the Feds want in.

Sad that Thomas and Gorsuch and ACB could not see this.

You despise common law? Well that's certainly an interesting position to take for a supposed libertarian. What do you prefer? The Napoleonic Code? Roman Law?

I despise precedent as encased in duty libraries. IANAL, so my "common law" is probably not congruent with many other people's definition.

I would rather every single verdict were arrived at from first principles, which in the US case would be the state and US constitutions. Precedents are what allows the current "interpretation" of the US Constitution to differ so radically from what it originally meant. The Slaughterhouse decisions are my favorite example, trashing the interpretations agreed by both pro and con during the debates over the 14th Amendment, the Plessey(?) decision just 30 years later which established Jim Crow was icing on the cake, and then came mandated racism with the Civil Rights Acts. All were based on precedent which was wrongly decided, and I despise it.

I agree re Slaughterhouse cases. Interestingly, the based on a discussion of this case (on Advisory Opinions) is seems like decisions like this make overruling the precedents like the Slaughterhouse cases more likely. The argument is that Bivens is really just made up by the Supreme Court and has spawned a variety of kludgy decisions-- just like the Slaughterhouse cases arguably spawned the whole notion of "substantive due process" to replace what really should have been based on the privileges and immunities clause.

I have not read the entire case, but the point here is that folks want the supreme court to create laws by judicial fiat, by interpretation. If I understand it correctly, what they are essentially saying is that the law needs to be changed and the judiciary doesn't do that. Congress does. This case hi-lights a problem that occurs over and over again. Congress either enacts a law it knows is unconstitutional and punts to SCOTUS to take responsibility for pointing it out, years after the law is enacted. OR Congress punts to regulators. Congress makes a law, general in scope and then depends of the regulation arm of the Executive branch to flesh out details that often are regulations, enacted by unelected bureaucrats, who have no accountability to the voters, and are often partisan. We see even today how regulations have created a baby formula problem and then someone takes credit for "solving" the very problem their lack of specificity created in the first place. There was a time when we cared to elect representatives who knew the constitution well enough to mark up legislation that they knew was constitutional in the first place. So YES, congress needs to stop playing their "punt the accountability game" and voters need to ask harder questions of those they vote for. Playing tactics instead of strategy is how some define "the adults in the room", when they are not thinking like adults at all, playing checkers rather than chess. Voters need to exercise their rights as citizens better than listening to "research" without attribution offered by MSNBC or FOX.

Except this isn't that there isn't a law against federal officers doing this sort of thing - there's an amendment against federal officers doing this sort of thing. So the Supreme Court's position is that it's not just illegal, but unconstitutional, but you can't do anything about it because congress never made a law with an explicit remedy.

That's BS for several reasons.

1. Prohibitions on government action without remedies basically aren't prohibitions at all. They're nullifying the bill of rights against the only actors it was originally intended to apply to - the federal government.

2. I'm pretty sure common law at the founding recognized a civil action against such an officer as a valid remedy, even without a statute authorizing it.

3. They say congress needs to create a remedy, but why would government create a remedy to protect citizens against government?

4. The bill of rights shouldn't need legislation to be implemented - those were guarantees extended to convince people to be governed by this government. It's downright breach of contract to say that they're unenforceable. Heck, SCOTUS is basically saying the only interpretation is its fraud by Congress. I'm no lawyer, but isn't there a canon of construction that says courts should not construe laws in these kinds of ways?

The logic here is that while the government can't do unconstitutional things, individual agents of the government have immunity for doing so until and unless Congress waives that immunity. The only redress that we peons get is to a) have the unconstitutional thing undone (such as conviction overturned) and b) throw the bums out in the next election.

Step two of the logic is that Congress did indeed waive immunity in Sec 1983 by granting a right to sue (since the evidence was clear that there were too many conflicts of interest to trust prosecutors and police to police their own ranks) - and the question is the proper interpretation of that waiver. Sec 1983 was passed in (or shortly before?) the Civil War. The interpretation of the scope of that waiver was expanded in the Bivens case (in the late 60s? - and subsequent Congresses have not repudiated that interpretation) but the original basis for that expansion is in debate.

Personally, I'd prefer to see a repudiation of the idea of immunity in almost all cases. Failing that, I'd like a more explicit right of redress that goes beyond just suing for money. But Thomas is right that it's the Legislature's job to fix that.

I'm curious what the original understanding regarding the bill of rights and remedies for violation were. Because I think Thomas et al are wrong for the simple reason that the courts would have understood there to be a common law remedy through civil action for damages in such cases.

re: "there to be a common law remedy"

I don't think that's right, though I'd be very glad to be presented with evidence to the contrary. From everything I've read or seen, the original understanding was that we citizens would keep our government under control by exercising our power at the ballot box. I am not aware of any common law remedy for individual violations, civil or otherwise.

The ballot box is a majoritarian measure. The bill of rights is an anti-majoritarian measure. There's no way the ballot box could protect the bill or rights - that's nonsense. The founders weren't that stupid.

That's an intriguing perspective. And yet, there is no evidence of a direct remedy (common law or otherwise) in place at the time of the Founding.

We didn't have federal police officers at the time of the founding. Part of the problem is in identifying a context in which you could even find that direct evidence.

But surely you don't believe the founders thought the Bill of Rights was meaningless and unenforceable?

Who said anything about criminal law?

What I think they're saying is, yes, you may have constitutional and other rights. But then the question is what happens when you're deprived of one? Is anyone personally responsible for the deprivation? Apparently it's up to Congress to write a statute saying who's responsible in which circumstances.

The court acknowledged that this person had a right to not have happen the things that happened. In this case the damage was done, and it can't be reversed, so the question was whether you could get money damages, and if so from whom? Can the damages be gotten from anyone without violating their rights?

My knee-jerk is to agree with what Thomas says. Reading quickly, it seems to be saying that the reversal is due to this being a legislative question not a judicial one, which I'm also sympathetic to. Gorsuch, who along with Kagan is one of the most vocal opponents of Qualified Immunity on the court, also joined the majority opinion. This indicates to me that there's something more at play here.

I'm reading the opinion though.

I don't know. I need someone with more legal knowledge than my very unprofessional amount.

It looks like it all centers around the ability of the courts to define new cause of actions that circumvent what the legislature has already defined. That is, Boule did take his charges to federal court against the defendant, and the defendant was found innocent. So, this seems to be a question of can the courts come up with new cause of action for a plaintiff to pursue charges, basically circumventing what the legislature has already defined.

I think? Just presume I'm wrong here.

Hmm. I don't know. This reads as an actually reasonable question of Judicial vs. Legislative power, with the court trying to rollback their own authority and push back things to the legislature.

I don't know. Just ignore these posts. I'm ignorant.

Can you clarify that? "Boule did take his charges to federal court" implies a civil action, otherwise it would be the government prosecutor taking the charges to court. Then this Supreme Court decision implies Boule appealed, except ... what? "found innocent" implies the charges themselves were found false (or whatever the legal jargon is; disproven?) and I didn't think that could be appealed. Did Boule lose because Egbert got qualified immunity?

Not meaning to pick on you. This case Supreme Court decision sounds bizarre to me, and I don't see how they could get there.

I think ignore me on this. I don't have the context here to speak in any detail of this. If I could delete my earlier posts I would have.

Also, didn't feel like you were picking on me. You were just asking me questions about what I was saying, and that makes sense because I'm not on solid footing with legal analysis.

Correct, but too many people jump to conclusions and take things personally, and even if you didn't, others could have, on your behalf of course.

Meanwhile, some 26-year old from California and previously Seattle tried to assassinate Kavanaugh last night:

https://notthebee.com/article/breaking-man-with-gun-arrested-outside-brett-kavanaughs-home-says-he-was-there-to-kill-scotus-justice

People who are dumber than my accounting manager are on the supreme court because they have the right beliefs about a nonexistent rabbi.

Sonia or Ellen?

Most people hire smarter people to do things they don't understand. Tony, on the other hand ....

Well, 3 of them are there because they have a gash between their legs. One is a self-admitted affirmative action hire. Not one of them is there because of their belief in any rabbi; the only justice whose religion includes rabbis is Kagan. And if you're talking about Yeshua the Nazarene, his historicity is not questioned by any serious historian or academic. Sounds like you should see if that accounting manager can explain religion, politics, and law to you.

Wait till you see his posts on energy. He probably should start back in middle school science first.

Courts and federal agents are on the same team, so this shouldn't be a surprise.

Seriously. Expecting the court to allow federal agents to be sued is about as silly as expecting a DA to prosecute cops who break the law. Everyone is on the same team. They watch each others backs. They're the ones who hold people accountable. They're certainly not going to hold one another accountable.

There are perverse incentives involved with courts, prosecutors and cops. None of which had fuck all to do with the legal reasoning here, however wrong or ill-advised. You're a simpleton, sarcasmic. Just read, don't post.

" The Supreme Court continues to shield federal officers who are accused of violating constitutional rights. "

The authoritarian right-wingers on the Court, more accurately.

Bitter clinger gun-loving deplorables, right?

This may be a shock to some conservatives, but conservatives are no better than liberals in the judiciary. I've often lamented that liberals bend the facts and the laws for whatever is politically correct while conservative know what to do just by looking at you.

Protecting the system comes first and victims are last priority. I remember a 5th Circuit opinion about an inmate that upset guards who place him in solitaire and disposed of his belongings. He sued and lost for due process violations since the lower court found "his complaint was only negligence and didn't rise to a civil rights violation." The 5th Circuit opined that the inmate was actually correct but that the court did not have enough time, courts, or judges to entertain complaints from the likes of an inmate. The court system is an adversarial system, not a justice system, and there is a pecking order. People are last on that list.

Thomas seems to be wrong and Sotomayor seems to be right.

There's a sentence I never ever expected to type.

What is wrong is expecting SCOTUS to legislate from the bench. And so many people refuse to see the role of Congress and congress laughs all the way to the voters booth. It's the law that needs to be changed and Congress does this. After years of congress not doing their job, years of enacting laws that are unconstitutional on their face and waiting for the "correction" to meander up thru the court system, after years of a "law" creating a certain outcome or culture, is unacceptable, except the process has become acceptable and members of congress know this. Add to this a press that refuses to report both side and let us decide for ourselves and you end up with oppression. Instead of blaming SCOTUS, which is easy to do, step up and put pressure on Congress which is harder to do than blame. You have a computer and an email account. Send off your message and get others to so the same. Ask the law makers how such a stupid thing happened in the first place and why it remains law in the second place. Citizenship is harder than complaining which is why most people don't exercise their rights beyond free speech and complaining (which is exactly what I am doing now BTW. I get it). 😐

Enforcing the constitution is not "legislating from the bench".

A right without a remedy is no right at all.

The logical gymnastics in which Thomas engages to distinguish this from Bivens are utter bull shit. At least Gorsuch had the balls to admit it isn't distinguishable and to just say essentially "fuck precedent, Bivens was wrong".

Sound decision. Many folk complain about the Qualified Immunity doctrine created by the Supreme Court in Harlow v. Fitzgerald but have no problem with the doctrine created by the Supreme Court in Bivens. Both are Court created causes of action and of defense. In this case the Court further seeks to limit Bivens and leave it to Congress to create causes of action. Makes sense. Congress allows for lawsuits against the Federal Government under the Federal Tort Claims Act, and that should be it.

The two are readily distinguishable. On the one hand, there is no constitutional support at all for QI, and arguably an amendment - 14A - that goes against it. On the other hand, there is a clear and enumerated constitutionally recognised right and it is bleeding obvious that a right without a remedy is meaningless.

Does Congress have to pass a law allowing citizens to sue for constitutional violations in other cases?

Yes

So a state can defend its anti-2A gun law by saying that Congress hasn't given plaintiff a remedy and so the suit must be dismissed?

You may be confusing two different things.

Someone accused under a 2A violating law can raise its unconstitutionality as a defense. In some circumstances, they can also preemptively sue to prevent the law from being applied to them.

They could not sue for damages (from the state or agents) for being prosecuted under the unconstitutional law unless there was a statute that provided a cause of action.

No. But it can be said that you have nobody to sue for the damages. A suit to invalidate the law is not a suit for damages.

re: "it is bleeding obvious that a right without a remedy is meaningless." and "Does Congress have to pass a law allowing citizens to sue for constitutional violations in other cases?"

No, it's not and Yes, they do.

To clarify, it maybe should be obvious that a right implies a remedy but that's not how our system is set up. Never has been. Congress passed Sec 1983 around the time of the Civil War (I think) to address this very problem. But yes, it required that congressional waiver of immunity.

excellent!

I read the comments and I recognize the ignorance - no offense. Immunity is a Supreme Court invention protecting the government and its employees. It is at odds with the constitution. The Supreme Court also invented the Bivens relief because there was no recourse against federal agents doing their worst to a family; because the Supreme Court gave them immunity. At least not statutorily when the agents "intended" to injure a family. Intending to cause harm is actually better protected under the court's immunity than unintentional actions. But the Supreme Court frames this as the legislature not keeping up it edicts, while its really the result of the Supreme Court protecting corruption by placing the government on a pedestal above its citizenry and non-responsive to the laws of our country. It really doesn't matter in the big picture because even if a victim jumps through every possible hoop and obstacle installed by the courts, all it takes is one order to destroy a lawsuit and all its efforts. There is no short supply of judges protecting the system and their paychecks, so ironically there is no justice. Interestingly, what happens when a citizen uses self-help to enforce his rights. We will find out soon in another story about government corruption.

Except that sovereign immunity is not a Supreme Court invention. It was built in at the start and must be explicitly waived before you can sue the government (and by extension, the individuals acting on its behalf).

Congress did waive immunity when it passed Sec 1983 but, as usual, was not as clear as they should have been with that statute. The Supreme Court interpreted that statute in the Bivens case - and now re-interpreted it. Maybe their interpretations are wrong but ultimately it's Congress' job to fix it.

So I've been doing some reading on the subject. You're wrong - individuals were not protected by sovereign immunity at the founding. Indeed, there was substantial business in Congress, up through at least the civil war, indemnifying individuals who had been found liable for tortes while performing their duties. It required a showing those individuals actions had been reasonable, even if tortuous.

See https://ir.law.fsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1040&context=lr

Start at the section at the bottom of page 99

The story is somewhat misleading. It implies that the Supreme Court has made it more difficult for citizens to sue a federal agent. It's not what the Supreme Court did that makes it harder. It's what Congress didn't do - provide a remedy for people who are victims of federal agent misconduct or outright law breaking. What the Court said was that the Bivens decision actually fashioned a court ordered remedy, when Congress should have done so. Article III courts have limited jurisdiction, that which is either provided by the Constitution itself, or which Congress gives it. For example, if you violate a federal law, the federal courts have jurisdiction over the case. Since Congress has not legislated on the matter of a federal agent abusing his or her powers, the courts can only sit as a reviewing court to determine if the proceedings themselves were tainted. They didn't go so far as to overturn Bivens, but it did say that the judicially formulated remedies were not favored in the absence of Congressional action. This ruling is certainly in line with the Court's recent jurisprudence saying that Congress needs to do its job, and not expect the courts to do it for them. Doing so would, in the minds of many, make courts activist if their decision doesn't favor them. Federal courts are not, except in very limited situations, courts of equity. We have state courts for that purpose.

You shouldn't have to rely on Congress passing laws to protect Constitutional rights in order to enjoy those rights.

Law defines the jurisdiction and remedy for the violation of the right. Without that definition, the courts would be making those up, i.e. legislating from the bench.

I think there should always be remedies for violation of rights so Congress should get off their ass and make the law for it.

Do you think that "the party of small government", the GOP, would readily pass legislation giving citizens the right to sue for constitutional violations?

It's the Republican justices making that argument, so maybe that's a hopeful sign. But really I think if either party wanted to do it, it would have been done already.

Why no criminal charges when agents outright break the law while abusing their power?

Now there is is the $54,000 question!

The answer, unfortunately, is that the prosecutors who would have to bring those criminal charges are entirely dependent on the same police (and their coworkers) for their success in the thousands of other cases. There are too many perverse incentives in the system for criminal prosecutions to be effective in all but the most egregious cases. That's why Congress passed Sec 1983 (around the time of the Civil War) - as an explicit waiver of the government's immunity in order to allow civil suits - that is, suits that can be pursued by regular citizens without the intervention of government-paid prosecutors.

Now, you could change the entire system to allow private prosecutions of criminal matters. Some other jurisdictions do exactly that. Belize, New Zealand and Singapore are a few examples. The experiences there, however, show that private prosecutions create more than a few of their own problems.

Exactly. We already have a right to sue for violation of rights, so there's no new law that needs to be written. As sarcasmic said, the agent should be facing criminal charges anyway. This civil stuff is a weak substitute.

Well said. Thank you. Exactly true. When laws are passed that are patently unconstitutional and congress punts to the courts, we should be ashamed of our representation not SCOTUS. And we should put heat on Congress for not doing what they are elected to do. But we have several justices for whom judicial Activision is their view of the world. They should quit and run for congress.

Nonsense. At the founding, federal officers were individually liable for tortes committed by private citizens. By foreclosing such suits, the Supreme Court is making it harder.

*tortes committed against private citizens, ug

It happens but not nearly enough. Even tougher to fix because DOJ/AG has discretion whether to prosecute and guess whose side they're on.

I'd say that makes it even more important that Congress provides a private cause of action.

Dammit. Was supposed to be a reply to sarc above

Why does Gorsuch, a purported defender of the Fourth Amendment, think Bivens should be overturned?

I'm a retired attorney. Lots of confused people here. They made the right decision. It's up to Congress to legislate, not the Court.

This is the court legislating. All the court's decisions finding for individual immunity to suit is a change to original practice at the founding.

Right's abuse by federal agents has been routinely protected by the SCOTUS since at least 1980. I know. I was a victim of three US Custom agents who were not required to justify their stop to a jury because they claimed "confidentiality". They asked the court to take their word that they had "probable cause" to stop me, but didn't have to be more specific because their criteria was "confidential". The judge agreed. The 9th Circuit Appeals Court agreed, but other Circuit Courts had ruled oppositely. However, the SCOTUS refused to settle the conflicting Appeals Court decisions by denying my appeal.