Politicians Cause Real Pain With Inflationary Policies

Inflation damages the economy while doing the greatest harm to the most vulnerable.

Gasoline prices just hit new record highs, and that's just the tip of the iceberg, inflation-wise. As consumers know, but federal officials seem slow to admit, everything is becoming more expensive. And while the purchasing power of our money is expected to erode more slowly in the months to come, getting from here to there will be painful. Unless you're a politician looking for a sneaky way to cover the government's bills, there's nothing good about inflation, which damages the economy while doing the greatest harm to the most vulnerable.

The average price for a gallon of regular gasoline across the United States is currently $4.62, according to AAA. That's up from $4.17 a month ago and $3.04 at this time last year. The White House wants to blame Russia's invasion of Ukraine for the soaring cost of driving (at least, when not hailing an "incredible transition" to green energy), which comes just in time to hobble Americans' summer travel plans. But, while that war certainly squeezed energy supplies, prices were rising before troops crossed borders in February, and they climbed for all sorts of goods and services as money lost its purchasing power.

"Housing, transportation and food are the three largest areas of the average household budget," CNBC noted in December of last year. "Inflation is pushing up these costs for consumers at the fastest clip in many years."

The situation hasn't improved in the months since that report. Prices rose across the board by 8.3 percent in April over the same time last year, according to the consumer price index compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That was a hair below the rate recorded in March, but still at a level not seen in 40 years. That means that even for those rare people whose paychecks keep up with inflation, the money in their wallets and bank accounts loses money as it sits there, buying less with each passing day. The effects are especially brutal for those with lower incomes.

"Price inflation often outstrips growth in wages and transfers, while self-employment income and investment income may be more likely to keep pace with inflation," Indermit Gill and Peter Nagle wrote for the Brookings Institution in March. "As such, inflation can reduce the incomes of poorer households relative to those of the richest."

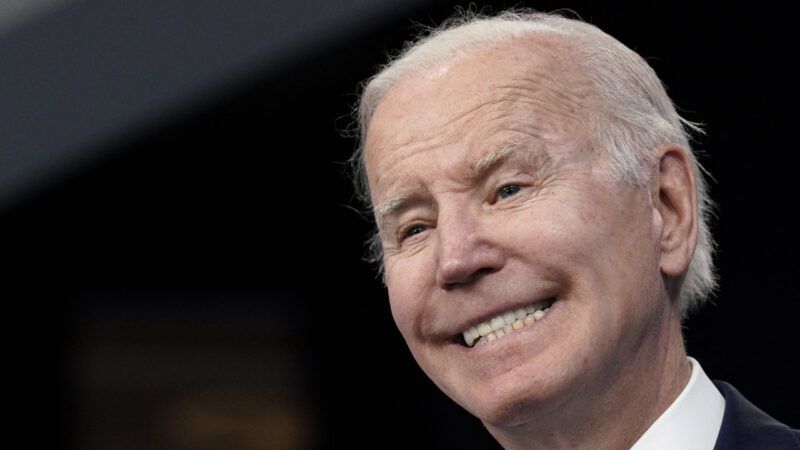

Worse, this situation is of human cause, largely as the result of a flood of government spending intended to offset pandemic lockdowns, or just to exploit the health crisis to advance preexisting legislative agendas. Economists from a variety of backgrounds, including the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and the Hoover Institution, lay the blame on trillions of dollars distributed by the federal government. President Joe Biden doesn't quite accept responsibility for fueling price increases, but he concedes the need to rein-in inflation.

"Americans are anxious," admits a Wall Street Journal op-ed published under the president's name this week. "I know that feeling. I grew up in a family where it mattered when the price of gas or groceries rose."

Inflation is pernicious because of the widespread destruction it wreaks. In destroying the value of money, it gnaws at incomes, erases savings, and makes budgeting challenging to the point of impossibility. In so doing, inflation causes chaos and erodes faith in the economic system.

"Lenin is said to have declared that the best way to destroy the Capitalist System was to debauch the currency," John Maynard Keynes wrote in Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919). "By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some. The sight of this arbitrary rearrangement of riches strikes not only at security, but at confidence in the equity of the existing distribution of wealth."

That inflation actually benefits some people through its uneven effects while hurting many more has been understood by economists at least since Richard Cantillon wrote on the subject in the 18th century. That creates resentment since those suffering see some people growing more prosperous and even advocating for devalued money.

Among the beneficiaries of cheapened money is the government itself. Inflation is often referred to as a "hidden tax" when government pays its bills by creating dollars (or pounds, euros, etc.) and the recipients get devalued currency for their troubles. But inflation involves taxes in another way, too.

"We are automatically shoved into higher brackets by the effect of inflation," observed the economist Milton Friedman in his 1980 Free to Choose TV series. "A neat trick; taxation without representation."

So, politicians and their appointees have plenty of incentive to flood the world with money for the benefit of their political agendas and their friends, but at the expense of the public at large. That temptation ends only when people scream loudly enough about rising prices and squeezed budgets. Unfortunately, the tools available to government officials to undo the damage they've done are blunt instruments that may well kneecap the economy by bringing about a recession.

"It is, of course, bad to lose 8 percent of your purchasing power to inflation," Megan McArdle warns at The Washington Post. "But it's even worse to lose a hundred percent of it to unemployment — and the collective suffering of those who lose their jobs is arguably much greater than the pains of households strained by inflation."

The smart bet is that the Federal Reserve will try to walk a tightrope with interest rate hikes intended to curb inflation without killing jobs and businesses. Observers aren't sure that's possible at this point; Deutsche Bank forecasts a deep recession for next year.

No matter what officials do, it will take time to stabilize the value of our money. The Congressional Budget Office sees the consumer price index coming down but says rising prices will linger into next year. "CBO currently projects higher inflation in 2022 and 2023 than it did last July; prices are increasing more rapidly across many sectors of the economy than CBO anticipated," analysts predicted last week.

That means economic pain at the gas pump, in the supermarket, and every time people sit down to pay their bills. Politicians will try to place the blame on anybody but themselves. But never forget that it was their decisions that placed that hole in your wallet.

Show Comments (122)