New CBO Report Exposes Biden's Deficit-Reduction Misinformation

The president is trying to claim credit for falling deficits. Actually, his administration has overseen a $2.4 trillion increase in the long-term deficit.

By the time inflation comes under control sometime next year, the federal budget deficit will be ballooning once again—and on course to hit $2 trillion annually by the end of the decade.

The new economic and budgetary outlook released by the Congressional Budget Office this week forecasts steady if unspectacular economic growth for the next 10 years, falling inflation rates, and climbing budget deficits. The report projects that "the current economic expansion continues, and economic output grows rapidly over the next year." But the government continues to spend more than it collects in tax revenue, driving annual budget deficits to $1.7 trillion by 2028 and $2.3 trillion by the end of the 10-year budget window in 2032.

The number-crunching agency expects inflation to fall to 4.7 percent by the end of this year and keep tumbling to 2.7 percent by the end of 2023 (only slightly higher than the Federal Reserve's long-term goal of 2 percent). That's good news for consumers, though it suggests that relief from 40-year-high inflation rates might not arrive as soon as many would like. The bad news is that the CBO expects economic growth to fall along with inflation: from 3.1 percent this year to a mere 1.5 percent by 2024.

But the CBO's projections are best understood not as a crystal ball providing information about future growth rates and inflation. Rather, the agency's long-term projections serve as a baseline—a literal one, when it comes to measuring the impact of new legislative proposals—for measuring how Congress and the White House have influenced future budgetary trends through recent policy changes. To really understand the usefulness of the CBO's projections, then, you have to look at what the agency was projecting last year and the year before that—then compare it to what the CBO is expecting now.

That's especially important to do right now because the Biden administration is pushing a wildly misleading talking point about the falling federal budget deficit. The deficit "has gone down both years that I've been here. Period. Those are the facts," the president said earlier this month.

As I've explained at length previously, the deficit is falling from the stratospheric levels that it reached during the COVID-19 pandemic because a lot of one-time, emergency pandemic spending is coming off the books. It's tricky because Biden is correct that the deficit is likely to fall by more than $1 trillion this year—even though this year's deficit is going to be larger than the deficit was in 2019, the last pre-pandemic year.

The CBO baseline is the best way to measure how deficits have grown or shrunk over multiple years since it filters out one-time emergency spending like the COVID relief efforts.

So what does the CBO have to say about how its budget baseline has shifted during the Biden administration's first full year in office?

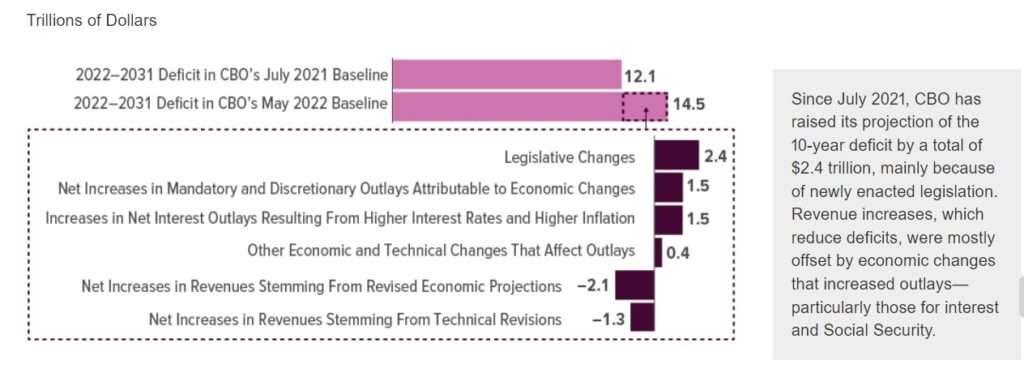

"Since July 2021, CBO has raised its projection of the 10-year deficit by a total of $2.4 trillion, mainly because of newly enacted legislation," the report reads. "Revenue increases, which reduce deficits, were mostly offset by economic changes that increased outlays—particularly those for interest and Social Security."

Those increased outlays—that is, spending—are mostly the result of the bipartisan infrastructure bill and the 2022 omnibus budget bill, which hiked spending by more than $600 billion.

In short, the deficit situation is getting worse. Even if it looks better in this particular year, the long-term trend is deteriorating thanks, largely, to interest payments on the ever-growing national debt and the increasing cost of entitlement programs.

Unlike the spiking deficit during the pandemic, the deficits projected over the next decade are unlikely to resolve themselves. The interest costs of the federal debt are creating a nasty feedback loop that drives deficits—and therefore borrowing—higher year after year, leading to more debt and higher interest payments in future years.

In fact, the CBO projects that interest payments on the national debt will triple by 2032, climbing from about $400 billion this year to more than $1.2 trillion that year. "Over the full decade, interest costs will exceed $8 trillion—comprising more than half the deficit and consuming all revenue outside of individual income and payroll taxes," notes the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a nonprofit that advocates for smaller deficits.

That should be a sobering assessment for America's political leaders, particularly because those costs are largely baked into future budgets already. It's time to pay the piper for years of accumulated deficits and fiscal nonchalance, and the price is a steep one.

But Biden is trying to claim credit for falling deficits as a way to justify even more government spending. The CBO's new projections—and the upward trend in the agency's baseline over the past 12 months—ought to put an end to those phony claims.

Show Comments (49)