He Was Arrested for Criticizing the Cops. A Federal Court Says He Can Sue.

Jerry Rogers Jr. complained that police hadn't solved a murder yet—and found himself in a jail cell.

The U.S. Supreme Court declared in 1987 that "the freedom of individuals verbally to oppose or challenge police action without thereby risking arrest" is one of the chief distinctions separating "a free nation from a police state." Some officials apparently needed a reminder about that, and this month the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana provided it.

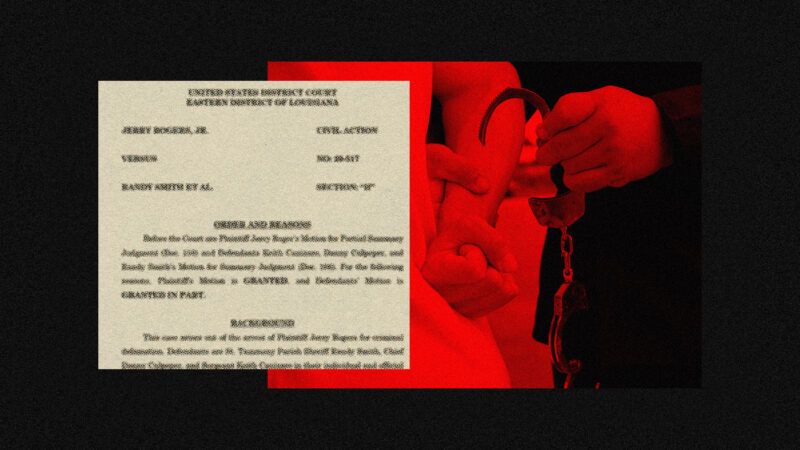

The court ruled that St. Tammany Parish Sheriff Randy Smith, Chief Danny Culpeper, and Sgt. Keith Canizaro violated clearly established law when they arrested and attempted to publicly humiliate a man for criticizing one of the department's investigations.

Jerry Rogers Jr. became apoplectic with the St. Tammany Parish Sheriff's Office in the years following Nanette Krentel's 2017 murder, which had gone unsolved and remains so. He began speaking with her family via email. His messages didn't sit well with the sheriff's office, which then sought to have Rogers indicted for defamation. The district attorney informed them that this was not constitutional, but Sgt. Canizaro proceeded anyway, obtaining what was arguably an illegal search warrant by citing a crime—"14:00000"—that doesn't exist and arresting Rogers for denouncing them.

The office then sent out a press release before he'd been booked. According to Canizaro's testimony, it had never done this before. It also filed a complaint with Rogers' workplace. According to Sheriff Smith, this had never been done either. The message sent to the community was clear: If you're alleged to have murdered or raped someone, you will receive less public shaming from the St. Tammany Parish Sheriff's Department than if you have the audacity to privately shame them.

When Rogers sued, the officers contended that they are entitled to qualified immunity, a legal doctrine that sometimes allows government actors to avoid lawsuits for infringing on people's rights if there is no prior court precedent that "clearly established" their behavior is unconstitutional. Put differently, the cops in St. Tammany Parish said there was no possible way they could have known what they were doing was a violation of the Constitution, even though the statute they used to arrest him had been declared unconstitutional half a century ago and even though the district attorney told them as much prior to seeking his arrest.

The judges didn't buy it. "This Court finds that no reasonable officer could have believed that probable cause existed where the unconstitutionality of Louisiana's criminal defamation statute as applied to public officials has long been clearly established," wrote Judge Jane Margaret Triche Milazzo, "and where the officers had been specifically warned that the arrest would be unconstitutional." The officers tried to circumvent this conclusion by claiming that, because no prior precedent said that police were public officials, they couldn't have known what they were doing was wrong. This sort of hair-splitting is common in qualified immunity cases, as the doctrine demands an absurd level of specificity. Sometimes it works. This time it didn't.

"Louisiana has seen a repeated, horrific pattern of law enforcement officers responding to criticism with handcuffs," says William Most, Rogers' attorney. "This ruling proves that they can be held accountable for their actions."

That doesn't mean Rogers has won his suit. But it means the claim will be allowed to move forward to a jury should the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit also side with him.

A similar case recently went before the 6th Circuit after Anthony Novak was arrested in Parma, Ohio, for creating a parody Facebook page that satirized the local police department. It was full of tasteless and unsavory humor mocking the town's cops, which led to a trial, an acquittal, and several appeals on the taxpayer dime. That time, the officers received qualified immunity.

Show Comments (29)