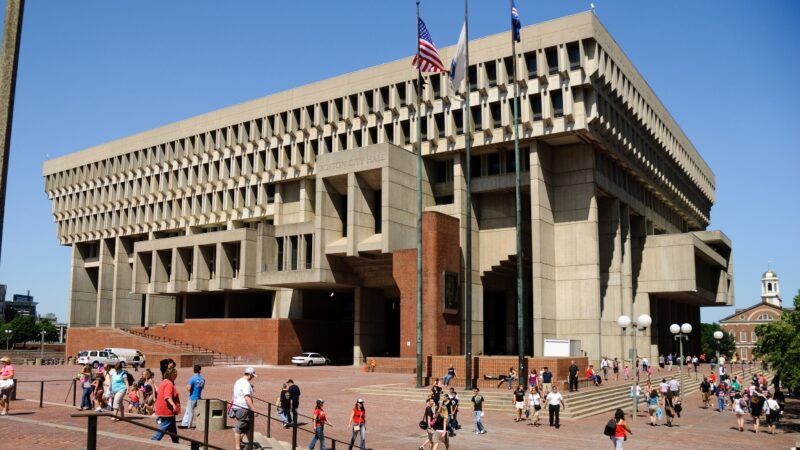

Supreme Court Rules Boston Was Wrong To Bar Christian Flag From City Hall

The justices unanimously agree that the city was not endorsing the flags, and that therefore it couldn’t exclude religious organizations.

The Supreme Court ruled 9-0 today that Boston violated the First Amendment when it allowed some private groups to fly flags outside City Hall while denying the same right to a religious organization.

For more than a decade, the city of Boston has allowed ceremonies for flags unconnected to the government to be flown in City Hall Plaza. Around 50 different flags have been raised there in close to 300 ceremonies. Some of them were associated with groups or causes.

In 2017, Harold Shurtleff, director of the Christian group Camp Constitution, asked to hold a flag ceremony there. He was rejected. Officials reportedly feared that allowing his organization to fly a flag would constitute endorsement of religion and violate the Establishment Clause. Shurtleff sued. Lower courts held that Boston was essentially engaged in "government speech" by allowing and hosting these flags. Therefore, the courts said, the government could reject Shurtleff without violating the First Amendment with the justification that they didn't want to get entangled with religion.

But in Shurtleff v. Boston today, the Supreme Court ruled that Boston's flag-raising program does not express government speech. Before Shurtleff's request, the city didn't vet anybody who requested to fly a flag or hold a ceremony at City Hall Plaza. The city simply approved them and had no written policies explaining what is or is not allowed. Because the city was not actually paying attention to what the flags represented before Shurtleff came along, the justices determined the flying of these third-party flags didn't amount to government-endorsed messages. Therefore, refusing Shurtleff's flag for religious reasons violated his First Amendment rights.

Justice Stephen Breyer (who heard arguments in the case before he retired last week) delivered the opinion: "When a government does not speak for itself, it may not exclude speech based on 'religious viewpoint'; doing so 'constitutes impermissible viewpoint discrimination.'" The Supreme Court ordered the previous ruling by the First Circuit reversed and kicked the case back down for reconsideration to incorporate the opinion.

Several of the more conservative justices wrote concurrences agreeing with the decision but also bringing up concerns about the way courts and government approach various religious speech tests. Justice Brett Kavanaugh noted that while the city may have believed it would violate the Establishment Clause by flying a religious flag, the Supreme Court has made it clear that the government doesn't violate the Establishment Clause by treating religious and secular speech with equal guidelines in the public sector.

Justice Samuel Alito wrote another concurrence (joined by Justices Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas) arguing that the court needs to more firmly establish when a speaker is purely private or government-endorsed, to avoid government censorship of private speech. He worries that cities' takeaway from the main opinion could be that they should establish rules for what sorts of flags would be allowed, which could put governments in the position of actually introducing viewpoint discrimination down the line:

Under the Court's factorized approach, government speech occurs when the government exercises a "sufficient" degree of control over speech that occurs in a setting connected with government speech in the eyes of history and the contemporary public, regardless of whether the government is actually merely facilitating private speech. This approach allows governments to exploit public expectations to mask censorship.

And Gorsuch (joined by Thomas) also wrote separately that the reason Boston (and other governments) consistently misunderstand the Establishment Clause is because of Lemon v. Kurtzman, a Supreme Court decision from 1971 determining that states violated the Establishment Clause by funding religious private schools. That decision established a three-prong test to determine whether a government policy entangled the church with the state.

Rather than resolving conflict, Gorsuch notes, the Lemon test has "produced only chaos" because the "seemingly simple test produced more questions than answers." What does it mean to "advance" or "inhibit" religious practice? When does the government get "excessively entangled" in religion? In this case, all the justices agreed that simply flying a flag did not entangle church and state—but lacking clarity, it's also easy to see why Boston officials may have thought they would violate the Constitution if they didn't reject Shurtleff's flag.

Gorsuch writes:

Faced with such a malleable test, risk-averse local officials found themselves in an ironic bind. To avoid Establishment Clause liability, they sometimes felt they had to discriminate against religious speech and suppress religious exercises. But those actions, in turn, only invited liability under other provisions of the First Amendment.

That's exactly what happened here. Gorsuch calls Lemon and the test it created "an anomaly and a mistake" that the Supreme Court has essentially stopped using in its decision-making. If so, local governments clearly haven't gotten the message.

Show Comments (73)