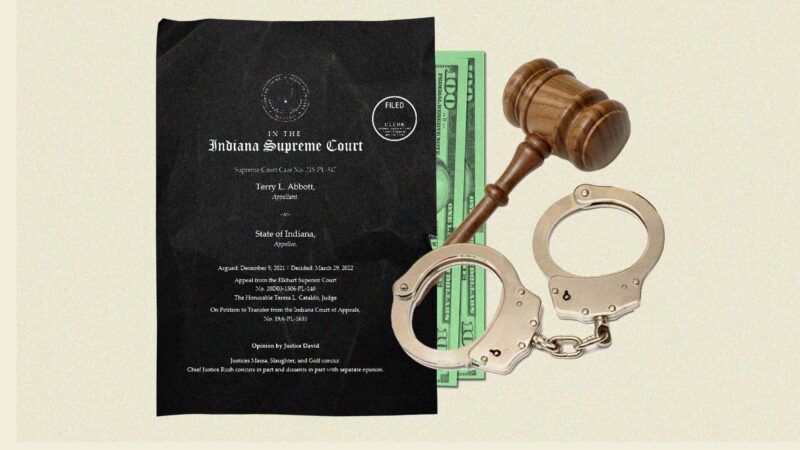

Police Seized Almost $10,000 From Him. A Court Ruled He Had No Right to an Attorney.

Terry Abbott couldn't afford representation, because the state took the cash he'd use to pay for it.

In April 2015, police in Indiana seized almost $10,000 from Terry Abbott after he was arrested for selling drugs to a confidential informant.

Cops used a process known as civil forfeiture, allowing them to proceed with pocketing those funds prior to securing a criminal conviction. Naturally, Abbott attempted to challenge that action in court. But he lost his attorney—as the money he would use to pay for that counsel had been taken by the state.

So for years he had to represent himself.

The Indiana Supreme Court on Tuesday decided that's in keeping with the law—ruling that defendants have no right to use their seized funds to finance legal representation.

"We do not find the legislature intended this language to give the court equitable authority to order the seized property released to the defendant to defend the forfeiture action," wrote Justice Steven H. David, noting that the court's hands were tied by the relevant statute on the books.

Central to the American criminal justice system is that every defendant is innocent until proven guilty. But civil forfeiture isn't a criminal action; it's a civil one, occurring in civil court, where defendants are not necessarily entitled to a lawyer. Only in certain extraordinary circumstances, the court ruled, is the state required to provide one.

Abbott didn't qualify. This means that, in cases like his, the government is able to put defendants in a chokehold by seizing the very assets that they would use to defend themselves against such a seizure. Fighting to get your cash back is a bit difficult when the government has taken all of your cash.

"One of the many pernicious things about civil forfeiture nationwide is that the government has the power to seize your cash, and your cars, and your home, but unlike in a criminal case, you don't have a right to appoint counsel," says Sam Gedge, an attorney at the Institute for Justice and a lawyer for Abbott. "So if you want to defend your cash, or your car, or your homes in a civil forfeiture action, you typically just have to pay for a lawyer yourself, and that's not surprisingly economically infeasible for lots of people who are targeted in civil forfeiture actions."

It is not an exaggeration to say that the state or the federal government can try to take you for nearly all you're worth in the process. People in Indiana may know that quite well. The state was the setting for one of the most high-profile forfeiture showdowns after Indiana took possession of Tyson Timbs' new Land Rover in 2013 following his arrest for a drug crime, setting in motion an almost decade-long legal circus between Timbs and the government. State officials were eventually required to return the vehicle in 2020. But prosecutors continued to fight, arguing before the Indiana Supreme Court in 2021 that there should be no proportionality—no limit—on what the government can seize in cases like Timbs'. (The state's highest court rejected that winning argument last summer.)

Yet civil forfeiture continues apace and is a source of police funding, with local and state departments able to keep the vast majority of the funds they take. Just last year, the Indiana Senate passed a bill to allow cops to seize assets from people suspected of committing "unlawful assembly," a charge so vague that whether or not someone committed it is somewhat in the eye of the beholder—who, in this case, would be an arresting officer.

Civil forfeiture is also used at the federal level, and it presents many of the same problems. In May 2020, the FBI seized almost $1 million from Carl Nelson after informing him he was under investigation for allegedly committing fraud. Two years later, no criminal charges have been filed, and the government returned some of the cash. Not unlike Abbott, however, the government's action made it a Herculean task for Nelson to push back, as he had been temporarily bankrupted. "If you can't afford to defend yourself, let alone feed yourself, it becomes complicated," Amy Nelson, his wife, told me in February.

As for the Hoosier state? "The ball is very much in the Indiana Legislature's court," says Gedge.

Show Comments (23)