This Program Aims to Correct the Culture of Acquiescence That Allowed Derek Chauvin to Kill George Floyd

"Active bystandership" training encourages officers to stop their colleagues from violating people's rights.

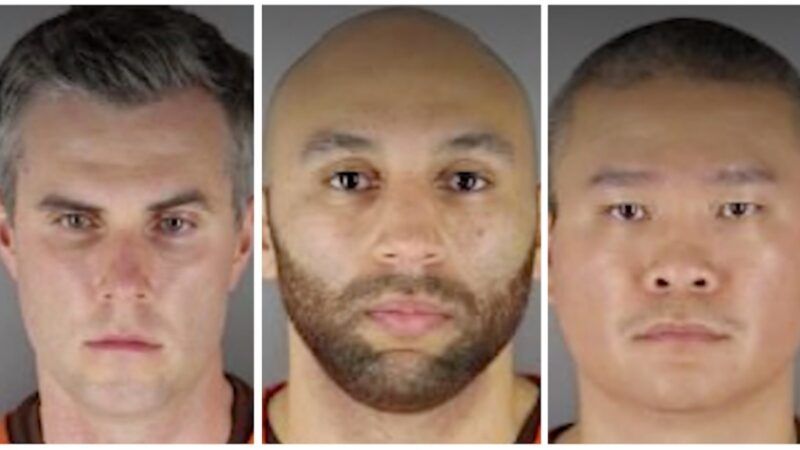

The federal trial of three former Minneapolis police officers who are charged with failing to stop Derek Chauvin from killing George Floyd resumed today. Much of the testimony presented by the prosecution has focused on the legal duty to prevent a fellow officer from using excessive force. The defense argues that the three officers, two of whom were rookies at the time of Floyd's arrest in May 2020, understandably deferred to Chauvin, the senior officer at the scene, as he pinned Floyd facedown to the pavement for nine and a half minutes.

The crucial question for the jury is whether J. Alexander Kueng, Thomas Lane, and Tou Thao "willfully" deprived Floyd of his constitutional rights by failing to intervene and/or render medical aid. But the trial also raises the broader question of how police officers can be encouraged to stop their colleagues from violating people's rights, especially when the perpetrator outranks them and is presumed to know more about proper procedure. A training program that has taken off in the wake of Floyd's death aims to answer that question by providing officers with the practical skills they need to intervene in situations like this.

Chauvin, who was convicted of murder and manslaughter last April, is serving a 22-year sentence in state prison. He also has pleaded guilty to violating 18 USC 242 by depriving Floyd of his constitutional rights under color of law. Kueng, Lane, and Thao are charged with violating the same statute, but the issue is not so much what they did as what they failed to do.

Kueng and Lane, who had arrested Floyd for buying cigarettes with a counterfeit $20 bill, helped Chauvin restrain Floyd as he repeatedly complained that he could not breathe and as bystanders repeatedly warned that his life was in danger. While Chauvin knelt on Floyd's neck, Kueng knelt on his back and Lane held his legs. Thao, who was tasked with handling the bystanders, alternately assured them that Floyd was fine and ordered them to step back when they tried to intervene.

Kueng and Thao are both charged with failing to stop Chauvin from continuing the prolonged prone restraint. Lane does not face that charge, presumably because he twice suggested that Floyd should be rolled from his stomach onto his side, consistent with what police are taught about the danger of "positional asphyxia." But all three officers are charged with showing "deliberate indifference to [Floyd's] serious medical needs."

Minneapolis Police Department Inspector Katie Blackwell, who resumed her testimony today, has emphasized that the defendants should have known, based on their training, that Chauvin's use of force was excessive and that they had a duty to protect Floyd. The defense has argued that the training the officers received was inadequate to prepare them for what happened that day.

While questioning Blackwell, Thao's attorney, Robert Paule, noted that department policy allowed officers to use their legs during a neck restraint, but "police officers received absolutely zero training on how to use a leg as a mechanism for restraint." Blackwell agreed.

Paule and Thomas Plunkett, Kueng's attorney, have also noted that the defendants were trained in the proper use of force but not in how to intervene when a colleague violates those rules. Blackwell conceded that officers are told they should never argue with a training officer.

Chauvin, a 19-year veteran, was Kueng's training officer. Kueng and Lane, who prior to Chauvin's arrival had tried unsuccessfully to force an agitated Floyd into the back seat of a squad car, were both new to the job. Kueng was working the third shift of his career. Thao had been a police officer for about 11 years.

The legal duty to intervene when another officer uses excessive force is well-established in the 8th Circuit, which includes Minnesota. In the 1981 case Putman v. Gerloff, for example, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit held that a deputy sheriff, James Crowe, could be held liable for failing to stop his supervisor, Sheriff Elmer Gerloff, from repeatedly striking a prisoner in the head with the butt of a shotgun. The prisoner had attempted to escape but was incapacitated at the point when the sheriff delivered those blows. "Although Crowe was a subordinate," the court said, "the evidence is sufficient to hold him jointly liable for failing to intervene if a fellow officer, albeit his superior, was using excessive force and otherwise was unlawfully punishing the prisoner."

While conceding that Kueng and Thao were aware of this duty, their lawyers argue that their training left them ill-equipped to comply with it. Given Chauvin's seniority, they say, it was natural for the defendants to assume he knew what he was doing, and their failure to contradict him in these circumstances does not amount to a willful deprivation of Floyd's rights.

Whether or not that argument sways the jury, the defendants have identified a real problem that police training frequently does not address. Granted that officers are supposed to do something in a situation like this, exactly what are they supposed to do, and how can they reasonably be expected to do it given the strong social and psychological pressures in favor of obedience and conformity?

Active Bystandership for Law Enforcement (ABLE), a training program that was established in 2021 and so far involves more than 200 police departments, aims to fill that gap. ABLE, which was developed by Georgetown University's Center for Innovations in Public Safety, grew out of a New Orleans program known as EPIC (Ethical Policing Is Courageous) that was launched in 2014 under the guidance of Ervin Staub, an emeritus professor of psychology at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. It is based on insights gained from research into why people either intervene or fail to intervene in emergency situations. The obstacles to intervention include deference to authority, diffusion of responsibility, and fear of retaliation and ostracism.

Jonathan Aronie, a partner at the law firm Sheppard Mullin, which sponsors ABLE, is chairman of the program's board of advisers. He says ABLE, which includes a week-long certification program for officers who conduct eight hours of training for their colleagues, is based on principles that have been proven effective for hospitals and airlines seeking to prevent surgical and pilot error. The challenge in those contexts is similar to the one exemplified by Floyd's death: overcoming the natural tendency to go along rather than risk negative consequences by challenging the judgment of colleagues and superiors.

ABLE, which demands explicit and conspicuous buy-in from police executives, local politicians, and community groups, strives to create a culture that reinforces the duty to intervene. The program, which is free to police departments thanks to support from Sheppard Mullin and several corporate donors, uses case studies and role-playing scenarios to identify and overcome the obstacles that prevented Kueng, Lane, and Thao from second-guessing Chauvin.

During a recent ABLE webinar, New Orleans activist Ted Quant, who said he had spent 50 years "protesting against police brutality," recalled an incident, prior to the creation of EPIC, when two officers who had undergone an earlier version of intervention training were punished because they forcibly stopped an officer who was beating a teenager. The difference, he said, was that at that point local police leadership did not support the changes that were necessary to address "the certifiably brutal culture of the New Orleans Police Department."

EPIC changed that culture, Quant said, and thereby equipped "the lowest-ranking officer" to "intervene with the highest-ranking officer to prevent each of them from making mistakes or doing harm." He gave a real-life example of what that means in practice, describing an incident in which "a young rookie police officer" de-escalated an argument between her supervisor and women who were selling liquor shots on the street in an area of the French Quarter where that was not allowed.

"The senior officer was telling them that they can't sell the drinks," Quant said. "The senior officer was being very professional and handling it, but the rookie could see that he was about to lose his temper and go off on these women, and there was going to be some mess."

The rookie's response was subtle but effective. "The rookie touched his sleeve," Quant said, "got his attention, and stepped in as if to say, 'I got this.' Now the senior officer gives a look like, 'Who do you think you are, telling me what to do?' And she pointed to her EPIC pin. When she pointed to her pin, and he sees this, he stepped back, and she took over. She de-escalated the situation and got compliance from the women, and as a result, there was no negative incident."

While that situation began with a minor offense, so did the arrest that led to Floyd's death. It is impossible to say what would have happened if the New Orleans rookie had not stepped in, but there was clear potential for violent conflict between women who were angry about being hassled and an officer who was losing his patience.

"EPIC creates stories that are never told because nothing happened," Quant said. "But something did happen: An incident was prevented. The rookie was really proud of what she did…She said, 'I EPICed him.' EPIC creates many untold stories."

ABLE aims to replicate those untold stories across the country. "When George Floyd was murdered," ABLE co-founder Christy Lopez told the Georgetown student newspaper last year, "one of the things that jumped out at many of us was not just Derek Chauvin's knee on his neck for so, so very many minutes. It was all the officers standing around who didn't really do anything at all. We're never going to prevent harm that could be prevented unless we focus on the bystanders who are in a position to intervene and make sure they actually intervene."

Show Comments (27)