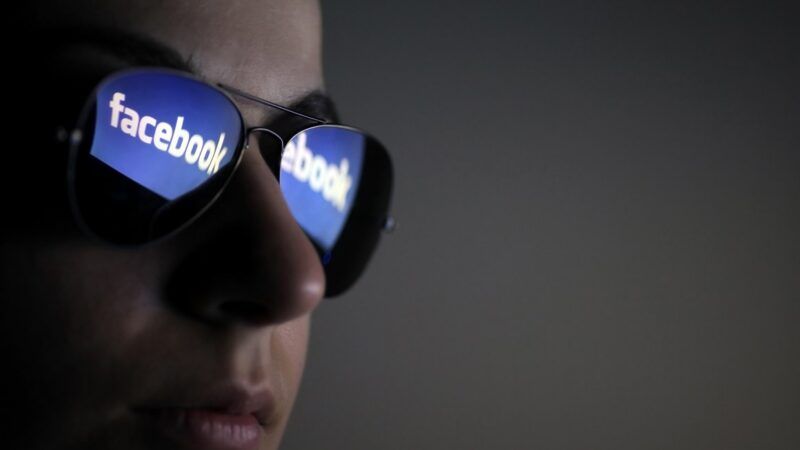

Facebook Is a Snitch

Social media accounts are windows into your activities, and the cops are watching.

This shouldn't be a revelation, but posting the details of your life online is not an effective way to keep secrets. Among those trawling for information are government agents who find social media an easy and low-cost means of gathering intelligence, often with the cooperation of both the platforms and their targets. Since the information is easily gathered, cops and their private-sector contractors snoop on us not just to investigate crimes but also while fishing for anything of interest. Worse, instead of curbing such abuses, many politicians want more.

"Social media has become a significant source of information for U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agencies," the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law noted in a report released last week. "The Department of Homeland Security, the FBI, and the State Department are among the many federal agencies that routinely monitor social platforms, for purposes ranging from conducting investigations to identifying threats to screening travelers and immigrants."

The problem of government monitoring of social media isn't new. In 2019, the American Civil Liberties Union sued the feds in an effort to force disclosure of social-media monitoring capabilities. Last September, U.S. District Judge Edward Chen finally ordered Customs and Border Protection to reveal its surveillance rules. But we found out soon thereafter that the agency routinely runs the names of people of interest, including journalists and activists, through databases, and checks them against information scraped from social media by private companies.

Private contractors actually play a big role in social-media surveillance. For years, the FBI used Dataminr, "a third-party service that can alert agents and analysts to important social media posts about breaking news, as well as when, where and how often key words and phrases appear in online posts," according to the Washington Post.

The FBI switched in 2019 to ZeroFox, which offers a similar service. Some FBI agents blamed their inability to anticipate the January 6 riot at the Capitol on the changeover, saying the transition caused them to miss posts and key-word searches that could have served as red flags of events to come. That's a stretch, though, since even government officials admit the difficulty inherent in parsing serious intent to commit illegal acts from jokes, memes, and ill-tempered rants.

"[A]ctual intent to carry out violence can be difficult to discern from the angry, hyperbolic—and constitutionally protected—speech and information commonly found on social media and other online platforms," Melissa Smislova, former head of Intelligence and Analysis for the Department of Homeland Security, told the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs last March.

That challenge is emphasized by the Brennan Center, which points out that "[s]ocial media conversations are difficult to interpret because they are often highly context-specific and can be riddled with slang, jokes, memes, sarcasm, and references to popular culture; heated rhetoric is also common."

Heated rhetoric, in particular, is easy to deliberately misinterpret when law enforcement agents are under pressure to find somebody on whom to hang a crime or are biased against a target. The Brennan Center focuses on the risks that mining social media poses "for the Black, Latino, and Muslim communities that are historically targeted by law enforcement and intelligence efforts" and there's no doubt that agents motivated by racial, ethnic, and religious animus can have a field day spinning off-the-cuff posts and tweets. But the fractured state of modern America makes it obvious that political bias is also a danger when law enforcement goes on the hunt for participants in protests gone wrong or seeks damning details about critics of whichever faction is currently in power.

Often, agents don't have to do their own heavy lifting beyond asking companies for data on their users. According to Vox's Recode, when the FBI looked into the movements of suspected participants in the January 6 riot, telecoms volunteered the locations of cellphones, Facebook offered up selfies posted inside the Capitol, and Google provided precise location data.

"Rather than revealing the breadth of the FBI's domestic surveillance capabilities, the majority of cases show the power of the tech industry to collect and collate vast amounts of data on its users—and their obligation to share that data with law enforcement when asked," Vox's Sara Morrison wrote.

Over the past year, law enforcement has come under pressure to engage in even more monitoring of social media because of its failure to anticipate the January 6 riot.

"You know, I think that, in part, is an intelligence failure that is the failure to see all the evidence that was out there to be seen of the propensity for violence that day, a lot of it on social media," House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff (D-Calif.) commented last week. "Now there are answers for why the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security failed to see it as clearly as they should have and we're looking into that."

Many critics of alleged law enforcement intelligence failures concede that the FBI and its sister agencies have a horrendous history of abusive surveillance of minorities, anti-war activists, and peaceful political radicals. They'd better; the abuses are well-documented.

"[T]he FBI … has placed more emphasis on domestic dissent than on organized crime and, according to some, let its efforts against foreign spies suffer because of the amount of time spent checking up on American protest groups," as the U.S. Senate's Church Committee noted in 1976.

But their takeaway seems to be that since the feds wrongly put some groups under the microscope in the past, it should extend its surveillance efforts more widely in the future. Instead of curbing abusive surveillance, their goal is to make sure that previously excluded groups get a taste. That might be fairer, by some twisted understanding of the word, but it's also incredibly dangerous.

"Government monitoring of social media can work to people's detriment in at least four ways," cautions the Brennan Center report. "(1) wrongly implicating an individual or group in criminal behavior based on their activity on social media; (2) misinterpreting the meaning of social media activity, sometimes with severe consequences; (3) suppressing people's willingness to talk or connect openly online; and (4) invading individuals' privacy."

But monitoring social media is so easily and casually done that it's difficult to see the practice being effectively curbed. Until somebody figures out a good way to rein-in government snoopiness, it might be better to avoid taking selfies at protests. And give some extra thought to how the things you post online might be interpreted by officials who have it in for you.

Show Comments (48)