We Keep Going Back to The Matrix

How a generation was redpilled by a nerd power fantasy about defining yourself in the digital age

In 1999, humanity tumbled down the rabbit hole of The Matrix, and the world was never the same. The film followed a group of hackers battling the sentient A.I. who had enslaved the unknowing human race inside a simulation—the titular matrix, a Descartes' demon for the digital age. There was a smorgasbord of '90s-era cinematic points, combining Hong Kong–style martial arts action with the geek chic of Hackers and the murderbot apocalypticism of Terminator 2. But despite the familiarity of the elements, it became a cultural event of unparalleled resonance, both long-lasting and widespread.

At the time, the movie's fandom comprised a motley crew of wildly disparate groups, each finding a slightly different meaning in its message. The nerds of the world went wild for the vision of a revolution fought in a virtual reality where their kind could live like kings. Evangelical Christians saw God in The Matrix, enthralled by the best modern-day Jesus narrative since Narnia.

Misfits and punks swooned for its goth-industrial aesthetic, then sneered at the latecoming poseurs who thronged to Hot Topic in its wake. And in the decades since, disillusioned cynics, from men's rights types to fans of Donald Trump, have adopted the film's catchall metaphor for self-chosen enlightenment—the decision to either take a blue pill and continue living in ignorance as a slave, or take a red pill and become awakened to the deep truth of the world around you—only to be hip checked by progressive activists pointing to the gender transitions of the movie's director-siblings, Lana and Lilly Wachowski, as evidence that the film was always actually a transgender parable.

They're all right—and they're all wrong. That's the thing about The Matrix, which, just like its titular simulation, doesn't care much about the hearts or minds of the people who are plugged into it. Inside the matrix, you exist as a projection of whoever you believe yourself to be; watching it from the outside, you can project onto it to your heart's content.

Like so many movies from the end of the last millenium, it's about office worker angst, mindless consumerism, a world on the precipice of being transformed by tech and all the anxieties that go with it. But The Matrix has survived and surpassed its Y2K-era peers: This movie alone stands as a prophetic myth about freedom in the digital age, the way that technology can both trap and liberate us, and how difficult it is (and also how empowering) to choose our own lives and identities—especially in a world of unlimited virtual possibilities.

As the film's script would have it, nobody can be told what The Matrix is. But for the uninitiated, here's the gist: The movie follows Neo, an office drudge with a paranoid mindset and a secret life as a computer hacker. Shortly after the title credits, Neo is awakened to the horrifying truth that his entire life has been a hallucination, a digital simulation created by intelligent robot overlords to enslave humanity after a war between men and machines destroyed most of the physical world. But Neo might also be humanity's shot at salvation, a prophesied chosen one capable of manipulating the simulation, known as the matrix, from the inside. (Spoiler alert: Yes. Yes, he is.)

After a lot of trippy action and novel-at-the-time visual effects—revolutionaries dodge gunfire in motion so slow you can see the air shimmer; a spoon warps like magic in Neo's hands—our protagonist saves his friends, falls in love, fulfills his destiny, and ensures a big-ass budget for the next two Matrix films.

If you weren't around for the film's theatrical release, it's hard to explain how groundbreaking it was—visually, technically, technologically. This was spring 1999: Television came into your house via cable, while the internet, if you had it, was a dial-up connection that tied up your phone line for hours. Nobody you knew had a cellphone, and smartphones didn't exist. Mark Zuckerberg was a 15-year-old kid in Dobbs Ferry, New York, closer to his Star Wars–themed bar mitzvah than his future as a Facebook founder. The slick digital world of The Matrix, a virtual reality better than the real thing, was a revelation.

Similarly, it's hard to overstate the long-tail impact of The Matrix on popular and political culture. More than two decades later, with a long-awaited fourth film due in theaters in late December, this movie is the ghost in all of our machines. In the movie, Morpheus, a John the Baptist–like revolutionary guru whose search for a savior kicks off the story, explains the matrix by describing its omnipresence. "It is all around us," he says. "Even now, in this very room. You can see it when you look out your window or when you turn on your television." The same might be said for the movie itself, which has left a vast imprint on everything from action movies to fashion to how we understand technology.

There's the super-slow-motion "bullet time" effect that turns action scenes into time-bending works of art; the wire work that allows a single punch to send a character flying through the air; the posed and choreographed fight scenes that define the contemporary action movie landscape and particularly the tentpole superhero films that make box-office millions every year. All these visual tricks are old hat now, but they were born, or at least popularized, in The Matrix.

There's the ubiquity of -pilled as a modifier to describe an ideological awakening, much like -gate to designate a scandal. It's not just that the idea of being "red-pilled"—often but not always to describe a right-wing or reactionary political awakening—has become such a common bit of internet-forum jargon that it's a cliché. Over the last year, tryhard left-leaning political analysts have begun to speak of being "Shor-pilled," after the pollster David Shor, who argues that the Democratic base is not nearly as stridently woke as the party's urban, college-educated leadership—another sort of political awakening.

There are even some prescient shades of our current discourse: Two decades before the COVID-19 pandemic spawned a million "we are the virus" jokes, the sentient computer program known as Agent Smith had humanity's number.

But The Matrix offered more than innovative effects and GIF-ready virus memes. It offered a new vision of cultural and personal power, built not around raw physical strength but around the ability to manipulate information. Look at its hero, who learns kung fu not from hours sweating in the dojo but by downloading the knowledge directly to his brain.

Over the next 20 years, the latter-day saints of tech would eventually emerge to fulfill its promise: men with big balls but bigger brains; men who, like Neo, could remake the world through code. Smartphones and social media would transform everything from the way we communicate with each other to our very conception of self: Facebook's recent pivot to a suite of virtual reality products known as "the Metaverse" probably won't live up to the seamless, reality-bending, all-consuming simulation imagined by The Matrix, but they share an underlying idea, even if Zuckerberg is trying to harvest personal data rather than literally turn humans into batteries.

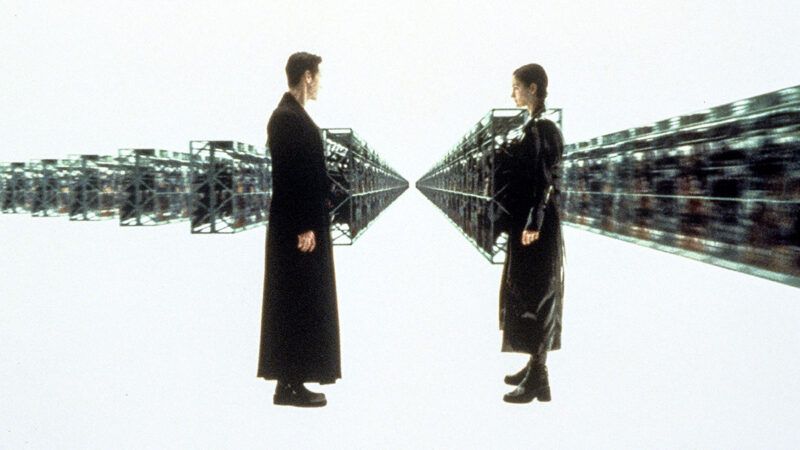

Part of the appeal of The Matrix's nerd power fantasy was its highly stylized aesthetic, which the fashion world has now recycled twice over. At the time of the movie's release, it spawned a veritable style revolution, particularly for a certain type of person, usually male, often socially awkward, who had never thought much about clothes before.

I saw the effects of this firsthand a few months after The Matrix came out, when I went to visit a high school friend who had always been, well, kind of a dork, and found him suddenly transformed.

I'll never forget the image of him walking through the doors of the Greyhound bus station in Albany, New York—a grim, fluorescent-lit setting with the same greenish tint that alerted viewers they were in The Matrix's simulation—in a floor-dusting black trench coat, combat boots, and wraparound shades. But it wasn't just what he was wearing. He looked six inches taller and had traded his slouchy walk for an action hero's swagger.

When I called to ask if he remembered this moment as well as I did, he told me that the Neo-themed makeover wasn't his idea—the clothes were given to him by a girlfriend who had a thing for goth chic—but what it did for his confidence was real. "I was such an awkward kid," he said. "The idea that you could reinvent yourself, that was so cool to me."

And you could reinvent yourself. In the matrix of the movie, fashion was like physics: based on rules that could be bent and even broken. Here was an aesthetic so ridiculous that it could only exist in a simulation, as anyone who's ever tried to do a split kick in a pair of pleather pants knows all too well.

That hasn't been lost on our present-day cultural commentators. The writer Freddie deBoer savaged it in a hilariously cranky essay-length complaint about the film: "Doesn't this look like some 11-year-old's vision of what cool people look like? Who walks around in all-black, all-leather everything? Can you imagine how they must smell on a warm day?"

He has a point—but only if you forget how nerds dressed before they had Neo as a fashion icon. All-black, all-leather everything might have been silly, but it was an improvement over the aesthetic crisis that was pleated khakis and huge, stupid basketball shoes. Years before Queer Eye for the Straight Guy unleashed its metrosexual tyranny on the wardrobes of aging, schlubby Gen Xers, The Matrix and its industrial goth hacker chic introduced countless young men to the wild and wonderful world of tailored clothing, and it was good.

Meanwhile, the leather-clad crew also highlights a key paradox: Neo and his pals have been liberated from the simulation, but that is still the only place they can go to express themselves. There are no leather hotpants in the desert of the real, where the struggle for survival takes precedence over matters of style.

This is the strange asceticism of The Matrix, one that explains its appeal to devout Christians and digital kids alike: As much as it indulges certain excesses in virtual space, it positively repudiates hedonism in the real world. Liberation is abnegation; the truly free folk spend their days eating amino acids and wearing rags.

Consider the scene where the crew of the Nebuchadnezzar sit around a table discussing the glop in their bowls, and the youngest of the bunch says it reminds him of a dish he had as a kid. "Did you ever eat Taystee Wheat?" he asks. Someone answers, "No, but technically neither did you."

Everyone laughs, but that's not the only thing our fine young friend never ate (ahem, wink, nudge). Technically, everyone still plugged into the simulation is a virgin, and yet the ones who've been liberated seem to live in a world where sex doesn't exist at all. It's strongly implied that these people limit their intimacy to virtual encounters with the woman in the red dress, a digital sexbot who "doesn't talk much" but will satisfy your needs. (She also appears to have no male counterpart.)

And the only moment of sensory pleasure in the film? Not only does it happen inside the simulation but it's enjoyed, crucially, by Cipher, the murderous Judas figure who chows down on a digital steak as he makes a deal with the machines to betray his comrades. For all that The Matrix fetishizes liberty, it has no sympathy at all for libertines.

The long tail on The Matrix is all the more remarkable for how thematically generic it was in the year of its release. The entertainment of the late 1990s—"the peak of your civilization," as Agent Smith caustically observes—was defined by an existential ennui that could only come amid a moment of relative peace and prosperity. "Is that all there is?" is the question asked over and over by Hollywood films from this period, from the slacker comedy of Office Space to the midlife navel gazing of American Beauty, from quirky entries like Being John Malkovich to gritty thrillers like Fight Club.

That last one became a cultural juggernaut in its own right, albeit with an ideological taint that The Matrix somehow managed to escape. It's worth asking why.

Here were two movies marinating in the same late-'90s nihilism, both critical of mindless consumer excess, both suggesting an escape from the Sisyphean drudgery of daily life and white-collar office work. And yet only one of them is supposed to represent a red flag if you find it among your boyfriend's DVDs.

Is it because The Matrix invites its adherents to wake up to freedom and meaning instead of meaninglessness? Or is it, perhaps, about men? Where Fight Club addressed a crisis of masculinity, The Matrix saw a bigger one, for humanity writ large. And where Fight Club slapped you right in the face with a subversive message—one that suggested that violence might not be the answer, but it was certainly an answer—The Matrix created a vision of the future in which physical strength was not just overrated but irrelevant.

Inside the simulation, nerds rule and jocks drool. Morpheus said it best, wearing a spotless black gi in a virtual zen dojo: "Do you believe that my being stronger or faster has anything to do with my muscles, in this place?"

Even amid the 1999 movie boom that often turned a critical eye on American consumerist culture, this film's explicit rejection of the sensory pleasures of meatspace, up to and including meat itself, made it unusual. Consider that 1999 was also the year of American Pie, the raunch-culture juggernaut about sex-starved teenage boys that spawned a multi-film franchise plus any number of knockoffs and dominated the comedy landscape for years to come. But two decades later, as our lives have moved ever more fully online, this might be the aspect of The Matrix that holds the most pressing, peculiar relevance.

Let's look again at the movie's fashion choices, the most striking of which is all that leather, which is so evocative of BDSM. Yet in the world of The Matrix, wearing these clothes—which, remember, you're not really wearing—is less about sex than it is about signaling your membership in Morpheus' tribe of enlightened outsiders. It's identity as aesthetic. Inside the matrix—and indeed, in the year 2021—the question isn't "How do I want to live?" It's "How do I want to be perceived?"

We live in a moment where identity is everything. But in a digitally driven world, what exactly is identity? How do we know who we are? Not by what we do, it turns out, but by who we claim to be. Our labels. Our posts. Our profiles. Our avatars. Our proclamations of self—I am this—which might only become real once other people validate them, echoing them back to us in the form of a like, a comment, a retweet. We can spend hours disengaged from our actual lives, gazing into the sterile mirror of social media, all in the hopes of catching a flattering glimpse of ourselves.

In the online world where many of us live part-time—and maybe too much of the time—we are both the spoon and the spoonbender: here to tell each other what is real, here to warp or be warped by each other's perceptions.

Our own matrix not only tells us who we are; it tells us that this is the only place where we can safely connect, be seen, and be ourselves. It begs us to keep scrolling, keep clicking, stay plugged in. It tells us, increasingly, that the real freedom is in here. Like Neo before his red-pilled revelation, it sometimes seems as if we might actually believe it.

We keep going back to the matrix—which might explain why we keep going back to The Matrix.

Shortly after his liberation from virtual prison, Neo has the mind-bending experience of returning to the simulation, this time with the knowledge that none of it is real. He holds a spoon in his hand—except that he doesn't, not really, because as a conveniently philosophical child informs him, there is no spoon—and watches it warp to his will.

The life he remembers living in this place was nothing but a dream, an illusion. He asks what it means. The answer? "That the matrix cannot tell you who you are." That's a pretty and powerful notion, not just of free will or self-determination but of some essential humanity that the sentient robot overlords in this dystopian future cannot touch. In The Matrix, the cage may confine you, but it does not define you.

Show Comments (14)