Is Fentanyl-Tainted Marijuana 'Something Real' or 'Just an Urban Legend'?

The meager evidence cited by Connecticut officials makes their warnings seem overwrought.

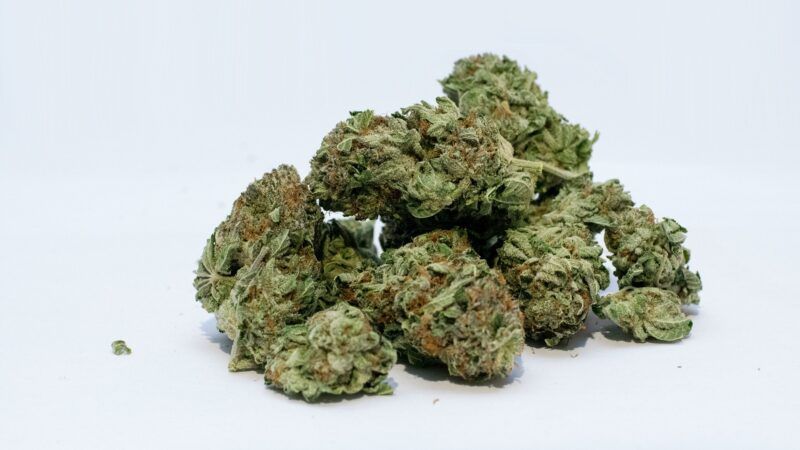

Taken at face value, recent reports of fentanyl-tainted marijuana in Connecticut highlight the hazards inherent in the black market created by drug prohibition. Consumers who buy illegal drugs rarely know for sure exactly what they are getting, and the retail-level dealers who sell those drugs to them may be equally in the dark. But even in a market where such uncertainty prevails, opioid overdoses among drug users who claim to have consumed nothing but cannabis—like earlier, better documented reports of fentanyl mixed with cocaine—raise puzzling questions about what is going on.

One thing seems clear: The official warnings prompted by those reports are more alarming than the evidence justifies.

The proliferation of illicitly produced fentanyl as a heroin booster and substitute during the last decade or so has helped drive opioid-related deaths to record levels. Fentanyl is roughly 50 times as potent as heroin, and its unpredictable presence has increased drug variability, making lethal errors more likely.

According to preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United States saw a record number of drug-related deaths last year: more than 93,000. Three-quarters of those deaths involved opioids. "Synthetic opioids other than methadone," the category that includes fentanyl and its analogs, were involved in about 83 percent of those opioid-related deaths, up from 14 percent in 2010.

Fentanyl and heroin have similar psychoactive effects. And since fentanyl is cheaper to produce and easier to smuggle than heroin, it makes sense that drug traffickers would use the former to fortify or replace the latter. But the idea that dealers would mix marijuana and fentanyl, two drugs with notably different effects, is much less plausible. Until now it amounted to nothing more than scary rumors.

Last week, however, the Connecticut Department of Public Health (DPH) announced that it has received 39 reports since July of "patients who have exhibited opioid overdose symptoms and required naloxone for revival" but who "denied any opioid use and claimed to have only smoked marijuana." The statement didn't say whether those apparent opioid overdoses were confirmed by blood tests. Assuming they were, the most obvious explanation is that the patients falsely denied opioid use, which carries a stronger stigma than cannabis consumption. But the department also reported that a lab test of a marijuana sample obtained in one of those cases detected fentanyl.

"This is the first lab-confirmed case of marijuana with fentanyl in Connecticut and possibly the first confirmed case in the United States," DPH Commissioner Manisha Juthani said. Based on that finding, her department "strongly advises all public health, harm reduction, and others working with clients who use marijuana to educate them about the possible dangers of marijuana with fentanyl." It says "they should assist their clients with obtaining the proper precautions if they will be using marijuana." It also "recommends that anyone who is using substances obtained illicitly…know the signs of an opioid overdose, do not use alone, and have naloxone on hand."

These warnings seem overwrought, given the meager basis for them. If the hazard Juthani describes were significant enough that it would be rational for cannabis consumers to "have naloxone on hand," you would expect to see many more suspected cases in a state with more than half a million marijuana users. Assuming the single lab test result was accurate, it is not clear how fentanyl ended up in the marijuana sample. Did a dealer intentionally add the fentanyl, and if so why? Could the sample have been contaminated accidentally by the dealer, his customer, or the lab? Did the patient, contrary to his denial, deliberately dose his pot with fentanyl?

Forbes writer Chris Roberts posed those questions to Robert Lawlor, an intelligence officer who works for the New England High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA), an interagency drug task force. "We have some of those same questions," Lawlor said. "From a business standpoint, it doesn't make sense to put fentanyl on marijuana. So why is this happening? What is the purpose behind putting it in marijuana? Those are some of the questions that are still out there."

Notably, HIDTA is not telling marijuana users they should be on the lookout for fentanyl in black-market cannabis. "Marijuana [mixed with] fentanyl has been sort of an urban legend for a couple years now," Lawlor said. "To try and decide whether it's something real or just an urban legend is important for public safety and public health."

There is considerably more evidence of fentanyl in cocaine. According to a February 2018 bulletin from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), testing of samples seized in Florida during the two previous years "revealed the widespread adulteration of cocaine with fentanyl and fentanyl-related substances." The bulletin said fentanyl or its analogs were detected in more than 180 cocaine samples, although it did not say how many samples were tested.

"The widespread seizures of contaminated cocaine indicate that drug dealers are commonly mixing fentanyl and fentanyl-related substances into the drug," the DEA said. "In some cases, this is done purposefully to increase the drug's potency or profitability (and customer base). In other cases, fentanyl is inadvertently mixed into cocaine by drug dealers using the same blending equipment to cut various types of drugs, such as heroin. Regardless, the adulteration often occurs without the users' awareness, which may lead to potential addiction and overdose incidents. Individuals who use cocaine occasionally are at an extremely high risk of overdose due to lack of experience and tolerance."

The prevalence of fentanyl in cocaine seems to vary widely across the country. While the DEA described such mixtures as common in Florida, for example, another DEA bulletin published the same month reported that fentanyl was present in "less than one percent of the total cocaine exhibits analyzed and reported in Pennsylvania for 2015 through 2017." Nationwide, NPR reports based on DEA data, the share of seized cocaine samples that tested positive for fentanyl rose from 1 percent in 2016 to 3.3 percent in 2020.

As the DEA's Florida bulletin indicated, it is not clear to what extent dealers are deliberately adding fentanyl to cocaine and to what extent consumers know what they are buying. Since American drug users have a long history of consuming stimulants together with opioids, these mixtures were not necessarily unintentional on either end. But such combinations are playing a growing role in drug-related deaths.

From 2010 to 2019, the CDC reports, drug-related deaths involving cocaine rose nearly fourfold, from about 4,200 to about 15,900. During the same period, according to a CDC database, the share of those cases that also involved fentanyl or its analogs rose from 4 percent to 64 percent. The fact that both cocaine and fentanyl were detected does not necessarily mean they were mixed together before they were sold, but it is consistent with the concern that such combinations have become more common.

The DEA's Florida bulletin concluded that the increase in drug-related deaths involving cocaine largely reflected "the growing use of cocaine-opioid combinations and particularly a cocaine-fentanyl combination." But "without additional information," the agency noted in its 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment, "it is difficult to distinguish whether spikes in overdose deaths are primarily [attributable] to intentional use of true drug combinations, ingestion of SOOTM [synthetic opioids other than methadone] containing only small elements of cocaine (or ingestion of cocaine with small elements of SOOTM), or dual use of cocaine and SOOTM at different times."

Drug-related deaths involving combinations of methamphetamine and fentanyl are also on the rise, but the increase has not been nearly as large as the increase in cocaine/fentanyl combinations. Between 2010 and 2019, the CDC reports, deaths involving "psychostimulants with abuse potential," the category that includes methamphetamine, rose nearly ninefold, from about 1,900 to about 16,200. During the same period, the share of those cases that also involved fentanyl or its analogs rose from 2 percent to 11 percent.

As with cocaine, it is not clear how often these deaths involved presale mixtures. In September, the DEA issued a "public safety alert" about "fake prescription pills containing fentanyl and methamphetamine." These pills resemble commonly prescribed medications such as Percocet, Vicodin, Xanax, and Adderall. The DEA warned that the pills "often contain" potentially lethal doses of fentanyl. "Additionally," it said, "methamphetamine is increasingly being pressed into counterfeit pills."

The DEA did not say how common it was for the same pill to contain fentanyl and methamphetamine, and its 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment did not discuss deaths involving both drugs. But the CDC says fentanyl is "commonly mixed with drugs like heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine," adding: "Fentanyl-laced drugs are extremely dangerous, and many people may be unaware that their drugs are laced with fentanyl."

There is little evidence to support Connecticut's grave warnings about fentanyl-tainted marijuana. Fentanyl in cocaine is much better documented, although it does not seem to be very common in most markets, and it is not clear to what extent people are snorting the combination unwittingly. However you rate that hazard, it is clearly a product of prohibition, since legally produced drugs ranging from hydrocodone to whiskey contain known active ingredients in predictable doses.

When the DEA warns people that "pills purchased outside of a licensed pharmacy," in contrast with "legitimate pharmaceutical medications prescribed by medical professionals and dispensed by pharmacists," are "illegal, dangerous, and potentially lethal," it is calling attention to the life-threatening hazards created by the policies it enforces. It is no coincidence that the upward trend in opioid-related deaths not only continued but accelerated when the DEA and other agencies restricted the supply of prescription pain pills. That crackdown simultaneously deprived legitimate patients of the medication they needed to control their pain and drove nonmedical users toward "potentially lethal" black-market products of unknown provenance and composition. And needless to say, fentanyl contamination is not a problem that physicians or patients need to worry about when they use pharmaceutical-grade cocaine.

Connecticut cannabis consumers spooked by the state's hyperbolic warnings about black-market marijuana will soon have a legal alternative. In June, Connecticut became the 18th state to legalize recreational use of marijuana, and licensed sales are expected to begin next year. Consumers of other drugs, however, will still have to contend with a black market where purity and potency are uneven and unpredictable, sometimes lethally so.

Show Comments (44)