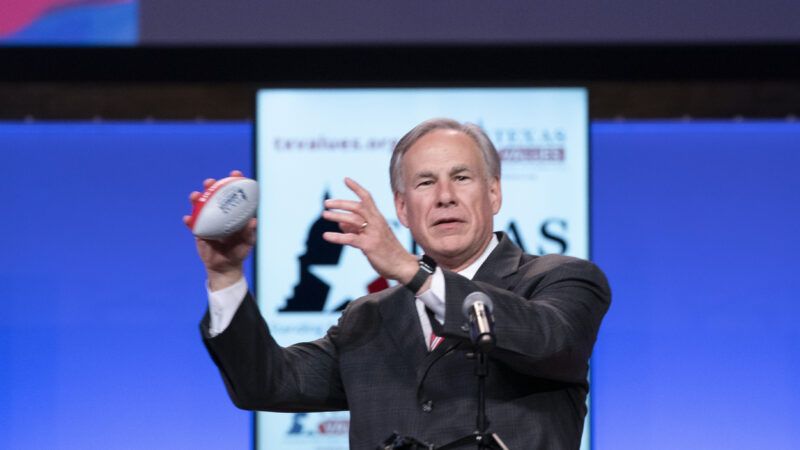

A Ruling Against Greg Abbott Suggests Federal Law May Require Schools To Mandate Masks

A federal judge concluded that the Texas governor's ban on mask mandates illegally discriminated against students with disabilities.

A federal judge this week barred Texas Gov. Greg Abbott from enforcing his ban on face mask mandates in public schools. U.S. District Judge Lee Yeakel ruled that Abbott's policy violated federal laws prohibiting discrimination against people with disabilities.

Yeakel's decision ostensibly leaves Texas school districts free to decide for themselves whether students and staff should be required to wear masks as a safeguard against COVID-19. But if school districts decide not to require masks, his logic suggests they could themselves be vulnerable to anti-discrimination lawsuits, which would effectively make federal advice on the subject mandatory.

The plaintiffs in this case are seven public school students who are 12 or younger and have various disabilities, including asthma, immune deficiency, Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, spina bifida, a heart defect, chronic respiratory failure, and underlying reactive airway disease. Those disabilities, the students' parents said, make them especially likely to catch COVID-19 or especially likely to suffer severe symptoms.

The parents argued that the executive order Abbott issued on July 29, which said "no governmental entity" may "require any person to wear a face covering," violated the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 because it prevented school districts from accommodating their children by requiring masks. The ADA prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities by state or local governments, including "all programs, services, and regulatory activities relating to the operation of elementary and secondary education systems." Section 504 prohibits such discrimination in programs that receive federal assistance.

The plaintiffs argued that Abbott's order had the effect of "placing children with disabilities in imminent danger or unlawfully forcing those children out of the public school system." Under the ADA, "no qualified individual with a disability shall,

by reason of such disability, be excluded from participation in or be denied the benefits of services, programs, or activities of a public entity, or be subjected to discrimination by any such entity."

Yeakel notes that ADA regulations address various forms of discrimination, "including discrimination that results from a public entity's implementation of facially neutral policies." He adds that "discrimination against individuals with disabilities results not just from intentional exclusion, but also from segregation; the failure to make modifications to existing practices; relegation to lesser services, programs, activities, benefits, or other opportunities; and exclusionary qualification standards and criteria."

The ADA prohibits "denying students with disabilities the 'opportunity to participate in or benefit from' a school's aid, benefits, or services that is 'equal to that afforded others'; denying students with disabilities 'the opportunity to participate in services, programs, or activities that are not separate or different' from those provided to non-disabled students; and denying students with disabilities the opportunity to receive a school's 'services, programs, and activities in the most integrated setting appropriate to the needs' of students with disabilities."

Yeakel notes that Abbott's order "prohibits school districts from adopting a mask mandate of any kind, even if a school district determines after an individual assessment that mask wearing is necessary to allow disabled students equal access to the benefits that in-person learning provides to other students." In his view, that amounts to "denying students with disabilities the equal opportunity to participate in in-person learning with their non-disabled peers," which "means that they are being 'excluded from participation in or be[ing] denied the benefits of the services, programs, or activities of a public entity.'" Abbott's policy, Yeakel says, "prevents local school districts from satisfying their ADA obligations to provide students with disabilities the 'opportunity to participate in or benefit from' in-person instruction that is 'equal to that afforded others,' that is 'not separate or different' from that provided to non-disabled students, and that is 'in the most integrated setting appropriate.'"

Does that mean the ADA requires school districts to enforce "universal masking," as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)? Maybe, although Yeakel leaves open the possibility that a narrower policy might be enough to comply with the ADA. He notes that Abbott's order "not only prohibits school districts from implementing universal masking in schools in accordance with CDC guidelines, but also from imposing limited mask requirements, such as in one wing of a school building or in one classroom, or by requiring an individual aide to wear a mask while working one-on-one with a student who is at heightened risk of serious illness or death from COVID-19."

Yeakel does not address the question of whether the plaintiffs' COVID-19 fears are reasonable. He mentions this year's "surge" in pediatric COVID-19 cases and "the emergence of the Delta variant of COVID-19, which is more than twice as contagious as previous variants." As of November 4, he notes, "6,503,629 total child COVID-19 cases have been reported in the United States, representing more than 16.7% of the total cases in the United States."

Yeakel does not mention that such cases are typically mild and almost never fatal. As of November 10, according to the CDC's tally, 595 Americans younger than 18 had died from COVID-19 since the beginning of the pandemic, which represents 0.08 percent of all COVID-19 deaths in the United States. By comparison, the CDC estimated that 486 minors died from the seasonal flu in 2019–20. The CDC estimates that the COVID-19 infection fatality rate for this age group is 0.002 percent.

The whole premise of this lawsuit, of course, is that children with certain disabilities face a higher-than-average risk of life-threatening COVID-19 symptoms. But even if their risk of death were 10 or 100 times as high, it would still be very, very small.

The availability of vaccines also should figure into this risk assessment. When Yeakel heard this case last month, all but one of the students was younger than 12, meaning they were not yet eligible for vaccination. But on October 29, the Food and Drug Administration approved the Pfizer vaccine for 5-to-11-year-olds. Even if some of the plaintiffs are medically disqualified from vaccination, which provides very effective protection from the worst consequences of COVID-19, vaccination of their fellow students will reduce the risk of in-school transmission.

Yeakel not only did not consider the magnitude of the danger that COVID-19 poses to children; he did not consider whether school mask mandates are a cost-effective response to that danger. "Plaintiffs here have alleged that the use of masks by those around them is a measure that would lower their risk of contracting the virus and thus make it safer for them to return to and remain in an in-person learning environment," he writes. "The evidence here supports that the use of masks may decrease the risk of COVID infection in group settings."

That is not exactly a ringing endorsement of school mask mandates, which are controversial in the United States and eschewed by many other developed countries. The evidence that the benefits of such policies outweigh the substantial burdens they impose is in fact quite limited and equivocal. But if making masks optional leaves school districts open to discrimination claims like these, local officials may be inclined to ignore the paucity of empirical support for that policy and impose mandates they otherwise would reject.

Yeakel frames his decision as one that favors local autonomy and flexibility—just as Education Secretary Miguel Cardona did when he announced that his department was investigating states that ban school mask mandates for possible violations of the ADA and the Rehabilitation Act. But the threat of litigation could mean that local school officials will be free to make their own decisions only if they settle on the policy that Cardona and the CDC favor.

Show Comments (199)