A Cop Was Indicted for Homicide After Shooting a Fleeing Driver. He Still Got Qualified Immunity.

Bau Tran might go to jail for his conduct, but he will be insulated from having to face a jury in civil court.

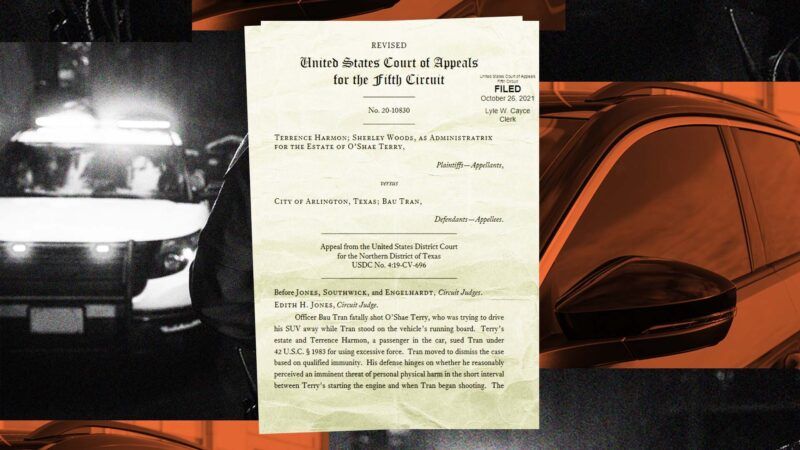

Bau Tran, a police officer with the city of Arlington, Texas, is currently facing up to two years in state jail for criminally negligent homicide after killing a motorist who was trying to flee a traffic stop. A jury of his peers will decide if Tran should spend time behind bars for reaching into O'Shae Terry's window and shooting him four times after the man was initially pulled over for an expired registration.

Tran will not have to face a jury in civil court, however, despite being sued by Terry's family and Terrence Harmon, Terry's passenger that day. Although Tran's conduct elicited a criminal charge, he still managed to receive qualified immunity in the civil suit. That doctrine generally insulates government officials from being sued over alleged rights violations if the rights at issue were not "clearly established" at the time of the alleged misconduct.

In September 2018, a different officer with the city's police department stopped Terry's SUV after noting his expired tag. That officer subsequently told Terry that she smelled marijuana and would need to search the vehicle. Tran arrived not long after and proceeded to stand by the passenger window, requiring that Terry and Harmon keep the windows rolled down and the ignition off. Though Terry initially complied, he eventually reached for the ignition and tried to drive away, at which point Tran jumped on the car's running board—the ledge under the door that helps riders board—and fired five shots into the vehicle, with four of them striking Terry.

Tran's case is a window into just how capricious a standard qualified immunity has become. Legislated into existence by the Supreme Court decades ago, it was supposedly enshrined into law as a way to protect state actors from facing doltish civil suits. Yet it has become so routine and so myopic that it protects people charged with homicide. That police officers very rarely find themselves in Tran's shoes—facing criminal charges for misconduct—speaks even further to the legal doctrine's harebrained nature: Prosecutors typically opt not to bring charges, and when they do, juries often acquit. Accountability is elusive in the criminal courts. That leaves the civil sphere, where accountability is needlessly elusive as well. Qualified immunity presents an onerous barrier to entry.

But here the alleged facts are so egregious that the state is proceeding with prosecution. So while a jury will consider if Tran should lose his freedom, Harmon and Terry's estate will still not be legally permitted to ask if monetary damages are also appropriate.

"To overcome qualified immunity, the law must be so clearly established that every reasonable officer in this factual context—an officer holding onto the side of a fleeing car where the driver has ignored instructions to stop—would have known he could not use deadly force," wrote Judge Edith H. Jones of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit. In doing so, her decision affirmed the lower court ruling that there was no prior decision exactly mirroring what happened between Tran and Terry.

Some would say that Tran's conduct did indeed meet the standard needed to overcome qualified immunity. As the 5th Circuit's opinion notes, "Tran retracted his right hand and rested it on his holstered pistol" prior to Terry moving the car forward, and he fired those fatal shots "about a second after" the vehicle was in motion. "One problem with the district court's fine parsing of the factual details between this case and prior cases is that, to the extent the facts here differ…they differ in a manner that made Officer Tran's use of deadly [force] even less reasonable," wrote the Cato Institute's Clark Neily and Jay Schweikert in an amicus brief supporting the plaintiffs. (Prior to that September day, Tran had nine demerits on his misconduct record, with the prosecution alleging it was a reflection of "bad character.")

Cato's brief also asked that the 5th Circuit formally rule Tran's conduct unconstitutional. Though qualified immunity often requires those suing an officer to furnish a preexisting court decision litigating a near-identical scenario, the Supreme Court has ruled that lower courts can analyze the case law while punting on the constitutional question entirely. It's created a vicious cycle, where plaintiffs are told to find a complementary decision that judges often decline to set when given the chance.

The 5th Circuit answered that request here, although in reverse: The appellate court ruled that Tran's conduct was specifically not unconstitutional. "Tran's use of deadly force was not excessive under the circumstances," Jones wrote, "because he could reasonably apprehend serious physical harm to himself as an unwilling passenger on the side of Terry's fleeing vehicle." Ironically, Tran's decision to jump onto the vehicle and kill Terry arguably put him in more danger, as the officer fell from the side while Terry lost control of the car as he was dying behind the wheel. (The body camera footage can be found here, and you can decide for yourself.)

When former Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin was convicted of killing George Floyd, I wrote that it was a reminder that we needed to reform qualified immunity. That's not because the doctrine has anything to do with criminal law; it doesn't. But it struck me that Chauvin could be convicted of murder—an exception to the rule—and still potentially skirt a civil suit filed by Floyd's family if no prior precedent had "clearly established" that it's unconstitutional for a cop to kneel on a man's neck for nearly nine minutes. Floyd's family avoided that scenario when the city opted to settle. But Terry's family has to confront that hypothetical as reality: The 5th Circuit has barred them from facing off with Tran in civil court, even as the state seeks a guilty conviction for committing homicide.

Show Comments (22)