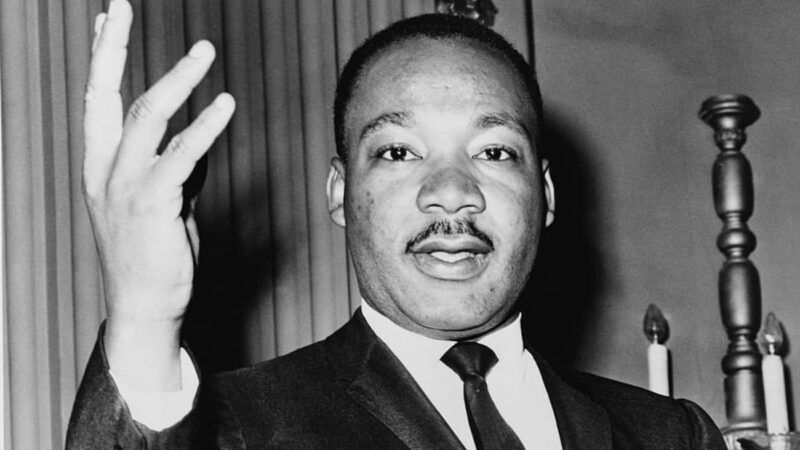

Why Martin Luther King Couldn't Get a Carry Permit

Several groups urging the Supreme Court to overturn New York’s virtual ban on bearing arms emphasize the policy’s racist roots and racially disproportionate impact.

After his home was bombed in 1956, Martin Luther King Jr. applied for a permit to carry a gun. Despite the potentially deadly threats that King faced as a leader of the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott, the county sheriff, Mac Sim Butler, said no.

Next week the Supreme Court will consider a challenge to a New York law similar to the Alabama statute that empowered local officials like Butler to decide who could exercise the constitutional right to bear arms. The briefs urging the Court to overturn New York's statute include several from African-American organizations that emphasize the long black tradition of armed self-defense, the racist roots of gun control laws, and their disproportionate impact on racial and ethnic minorities.

"I went to the sheriff to get a permit for those people who are guarding me," King told fellow protest organizers at a February 1956 meeting. "In substance, he was saying, 'You are at the disposal of the hoodlums.'"

At the time, it was illegal in Alabama to carry a pistol "in any vehicle" or concealed on one's person without a license. The law said a probate judge, police chief, or sheriff "may" issue a license "if it appears that the applicant has good reason to fear injury to his person or property, or has any other proper reason for carrying a pistol."

Nowadays, Alabama, like most states, requires law enforcement officials to issue a carry permit unless the applicant is legally disqualified. New York, by contrast, demands that applicants show "proper cause," an amorphous standard that is not satisfied by a general interest in self-defense.

As the National African American Gun Association notes in its Supreme Court brief, Southern states historically used that sort of discretionary carry permit law to disarm black people, leaving them at the mercy of white supremacist violence. African Americans who defied the law risked arrest for exercising their Second Amendment rights.

That remains true in New York, as the Black Attorneys of Legal Aid and several other public defender organizations note in their brief. "Each year," they say, "we represent hundreds of indigent people whom New York criminally charges for exercising their right to keep and bear arms," nearly all of whom are black or Hispanic.

That situation is unsurprising, the brief says, given the origins of New York's gun licensing regime. The Sullivan Act of 1911, which required a license to own handguns and "gave local police broad discretion to decide who could obtain one," was enacted after "years of hysteria over violence that the media and the establishment attributed to racial and ethnic minorities—particularly Black people and Italian immigrants."

A brief from Black Guns Matter argues that New York's law is of a piece with the firearm restrictions that Southern states imposed after the Civil War. When the 14th Amendment prohibited explicitly racist laws, white supremacists switched to facially neutral rules that in practice made it difficult or impossible for black people to defend themselves.

Black Guns Matter emphasizes that "armed self-defense has always been vitally important to the African American community"—a tradition that stretches from the struggle against slavery through the civil rights movement. Until relatively recently, as Fordham University law professor Nicholas Johnson details in his 2014 book Negroes and the Gun, mainstream black organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) steadfastly upheld that tradition.

Not anymore. The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which grew out of a fundraising campaign based on the successful defense of black people who used guns to resist racist aggression, supported the local handgun bans that the Supreme Court overturned in 2008 and 2010.

In the New York case, the organization argues that the state's virtual ban on public carry is an "important tool" in addressing urban violence. It does not even entertain the possibility that armed self-defense might be an important tool in responding to the same problem.

© Copyright 2021 by Creators Syndicate Inc.

Show Comments (45)